Emily Grant Hutchings, born in Hannibal, MO. who claimed to have written a book dictated by Mark Twain via the ouija board. More on Hutchings including her 1902 correspondence with Mark Twain. |

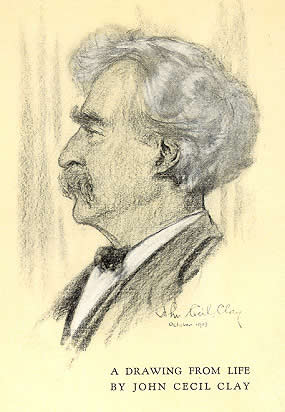

Frontispiece portrait of Twain for JAP HERRON |

Did Mark Twain dictate a book via the ouija board seven years after his death?

That was the claim put forth by Missouri writer Emily Grant Hutchings who, along with spiritualist Lola Hays, claimed to have communicated with the spirit of Mark Twain via the ouiji board in the composition of an "after death" manuscript titled JAP HERRON. Hutchings, like Sam Clemens, was a native of Hannibal, Missouri. She was the daughter of Carl H. Schmidt, an official of the Hannibal and St. Joseph Railway Company and his wife Margaret, who held the reputation of being one of the first female physicians in the Mississippi Valley. Emily attended the public schools in Hannibal. She later taught Latin, Greek and German, in the Hannibal high school. After leaving Hannibal, she relocated to St. Louis and worked as a feature writer on the St. Louis Republic and contributed to such magazines as Cosmopolitan and Atlantic Monthly. She married Charles Edwin Hutchings in 1897. Twain corresponded with both Emily and her husband Edwin Hutchings in 1902 after visiting St. Louis and advised her on her writing.

JAP HERRON was published during a time when the ouija board communications of "Patience Worth" via St. Louis writer Pearl Curran, a friend of Hutchings, was also capturing national attention. Prior to the book's release, the Literary Digest of October 14, 1916 reprinted the rumor which has circulated in the Newark Star-Eagle:

|

Nearly everybody in St. Louis is monkeying with "weejie-boards" and talking to dead novelists! The call for the little heart-shaped things on wheels, known as ouija-boards by the elect, has sent prices shooting skyward, and shipments of them are coming to St. Louis from all over the country. Mark Twain is the latest author said to speak to those on earth by this unearthly means, and it is whispered there is discord among those spooks who are seeking possession of the mental pipe-lines to the mystic pointers. (Literary Digest, October 14, 1916, p. 960.) |

Hutchings's JAP HERRON was published in the fall of 1917 by renowned book dealer Mitchell Kennerley and contained a frontispiece portrait of Mark Twain drawn by artist John Cecil Clay. A lengthy introduction to the book by Emily Grant Hutchings detailed how she and Lola Hays began receiving messages from Twain in 1915 using the ouija board.

On September 9, 1917 The New York Times published a less than flattering review of JAP HERRON. Shortly thereafter, Twain's surviving daughter Clara Clemens and Harper and Brothers publishers, who for seventeen years had owned the sole rights to Mark Twain's works, went to court to halt the publication.

The newspapers followed the story for several weeks and expected a Supreme Court legal showdown. However, the case never went to trial. Mitchell Kennerley, who had recently taken on a position with the prestigious Anderson Galleries, Incorporated art auctioneers had no time or taste for a lawsuit and he and Hutchings agreed to halt the distribution of the book. Hutchings and Kennerley agreed to quietly withdraw the book from publication and most of the copies were destroyed. Copies are rare and those with the original dust jacket are even more so.

_____

Read the biography of Hutchings and her correspondence with Mark Twain in 1902.

Read a synopsis of JAP HERRON by

Dave Thomson.

|

Read The New York Times news reports on JAP HERRON and the ouija board lawsuit: September 9, 1917 - BOOK REVIEW

- LATEST WORKS OF FICTION - JAP HERRON February 12, 1918 - [Editorial] Annoying, but Not Dangerous. |