EMILY GRANT HUTCHINGS

author of JAP HERRON

By Barbara Schmidt © 2019

Emily Grant

Hutchings (1870-1960)

Emily Grant Hutchings whose maiden name was Emily Rosalie Schmidt was born

in

Hannibal, Missouri, January 30, 1870. She claimed her novel JAP HERRON

(1917)

was dictated to her by Mark Twain via the ouija board ten years after his

death.

(Photo from NOTABLE

WOMEN OF ST. LOUIS edited and published by Mrs. Charles P. Johnson,

1914.)

_____

Emily Grant Hutchings and her husband Edwin apparently made their first acquaintance of Mark Twain when he visited St. Louis, Missouri in June 1902. Twain addressed the Art Students' Association, at a luncheon in his honor, on June 7, 1902, in the old Museum of Fine Arts, at Nineteenth and Locust Streets. Professor Halsey C. Ives, Director of the Museum and head of the school connected with it, conferred upon Twain the humorously conceived degree of "Master Doctor of Arts," just before the address was made.

In 1932 Cyril Clemens, a distant cousin of Samuel Clemens, published a book titled Mark Twain, the Letter Writer (Boston, Meador Pub. Co) which provided the text of the speech that day as well as two letters Mark Twain had written to Edwin Hutchings and his wife Emily. Cyril Clemens's text is the only source for the speech. For many years, the book was also the only known source for the text of these two letters to the Hutchings couple. The first letter is a "thank you" note to Edwin Hutchings for providing a text of the speech that day:

| Riverdale

on the Hudson, June 12/02.

Dear Mr. Hutchings: I ought to be very grateful to you for making that verbatim report and printing it, and I am. Long-hand reports have embittered my life for 30 years, for no matter how bad a speech I may make they manage to make it twice as bad as it was when I disgorged it. And so I thank you. With my kindest regards to Mrs. Hutchings "once of Hannibal" and to you, I am Sincerely yours, S. L. CLEMENS. |

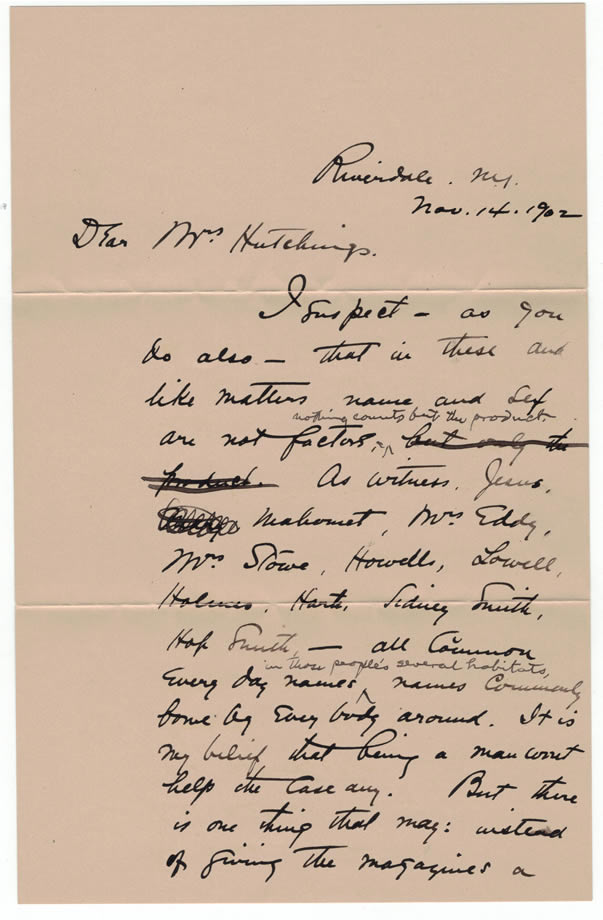

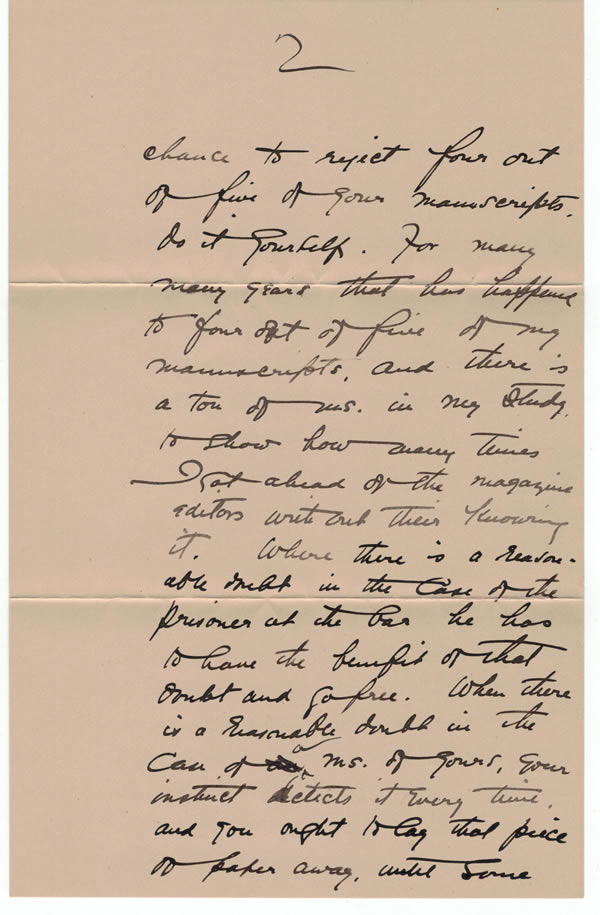

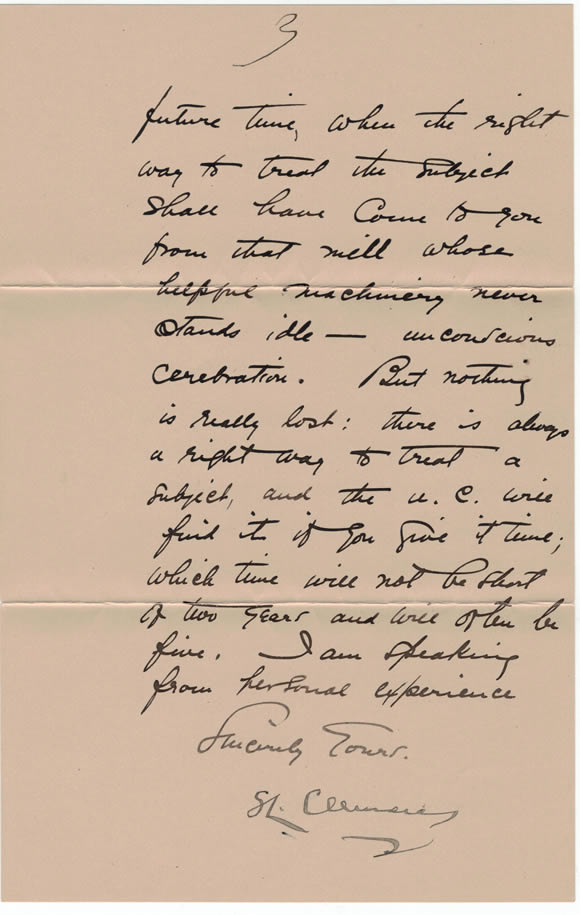

In November 1902, Twain replied to a letter from Emily Grant Hutchings which is presumed lost. Twain's letter of reply was acquired by Kevin Mac Donnell of Austin, Texas in 2016. According to Mac Donnell, the text of the 3-page letter is in the handwriting of secretary Isabel Lyon, with the exception of two corrections in Twain's handwriting on the first page. The mailing envelope was addressed to Hutchings at the St Louis Museum of Fine Art, Office of the Director. Mac Donnell writes:

I find the letter interesting because it was dictated and therefore reflects Twain's speaking voice. I like the letter's content. Right at the end Twain is describing the "fits and starts" writing method he used on Huckleberry Finn. Scholars assume he stopped work on mss whenever he ran into a stumbling block, but that's not exactly what he says in this letter.

Pages from Mark Twain's letter to Emily Grant Hutchings with the transcription following each page:

|

Riverdale,

N.Y.

|

|

Sincerely yours, S. L. CLEMENS. |

Several days later, Emily replied to Clemens's letter. This letter has been preserved in the Mark Twain Papers at the University of California, Berkeley. Grateful acknowledgment is given to Dr. Robert Hirst for providing the text:

| Saint Louis

Nov. 17, 1902

Dear Mr. Clemens - Your good, helpful letter was on my desk when I came in this morning. What you say I have long felt. I wrote a Civil War story when I was scarcely twenty. I have had it on the shelf for ten years, and now at odd times I am making its clothes over. The body needs few changes, but the dress! Gen. Wallace told me my plot was fine, but that I was too young to write a novel of which would not be ashamed at thirty. Munsey would have published it in 1895 but I was wise enough to take it back home with me, and now I am glad I did. This may be true of all the manuscript I have on hand now. I do not enjoy the modern magazine fiction. It is shallow for the most part, and I fear I am a little out of season. A story must be unusual and clever. When I essay the unusual and the clever I make an idiot of myself. I must write the thing as I see and feel it. Yet I am determined to fight it out on my own line. I have no other choice. Just now I want to earn money, to aid my husband in his new business and that is why I am impatient. I need this lesson, as I need all the lessons of life. Is it not so? The problem that confront me is very different from the problem you had to face, forty years ago. It is much more difficult to get an oar in where so many other oars are fighting for place in the current. I never could write as you do. That I know. You are unique, and the world realizes it; but if you had to make your start now I believe you would have an up-hill pull, simply because there is meat in what you write. It isn't all cleverness. We read of Mrs. Clemens' illness. I trust she is better. I wish I could send my sister to you. She is the finest trained nurse in America. Gratefully

Yours |

In 1914, prior to Emily Grant Hutchings's involvement in the JAP HERRON controversy, a biography of her appeared in the reference book NOTABLE WOMEN OF ST. LOUIS edited and published by Mrs. Charles P. Johnson, 1914, pages 110 - 114. The book is now available online at archive.org.

|

Emily Grant Hutchings has gained a wide reputation because of her meritorious work for newspapers and magazines. She is a regular feature writer for the magazine section of the Sunday Globe-Democrat, having filled this position for twelve years. Usually her articles are signed only with the initials "E. G. H." She was the "Mysterious Woman About Town," published in that paper for four years. There was considerable speculation as to the identity of the writer, but this was not disclosed until after the articles were discontinued. Following this she wrote the "Saturday Dinner Sketches," using the name of "Frank Harwin." Poetry and fiction have been contributed by Mrs. Hutchings to very many magazines--Current Literature, Cosmopolitan, Country Life, Current Magazine,The Open Court, Philistine, Atlantic Monthly, and others. She wrote one novel that was published in the Sunday Associated Magazine of Chicago, entitled "Chriskios-Divine Healer." For two years she wrote Art and Home Decorations for Beautiful Homes. This was a monthly magazine published in St. Louis. Ten chapters of the Woman's Atheneum are her contribution to a work in ten volumes, which is being edited by Vincent S. Byars of St. Louis, and which covers every phase of woman's activity. These ten chapters include such themes as Art in Dress; Art in Home Decorations; The History and Study of Art; Women as Writers; The Teaching Profession for Women; The Ethics of Handiwork for Women, etc. During the World's Fair in St. Louis in 1904, Mrs. Hutchings was on the staff of the General Press Bureau, writing a story a day for twenty four weeks, which were printed all over the world. In their preparation she interviewed practically every official and head of the departments connected with the fair. She wrote all kinds of stories, from "The Process of Making Liquid Air" to "Why the Igorottes Refused to Wear Clothes." Before the opening of the Fair her name was suggested to the press bureau as a valuable acquisition to the staff which was composed almost wholly of people who lived out of St. Louis. Walter Stevens requested that she interview Halsey C. Ives, the director of the Fine Arts Department, and prepare a sketch of this department that could be used in the advertisements of the Fair. Mr. Stevens felt that Mrs. Hutchings could do this because she had held the position of librarian and lecturer at the St. Louis School of Fine Arts and knew Professor Ives very well, having been associated with him in this connection. This article pleased the press bureau so well that she was selected to write occasional stories, and the first one was "Foreign Mothers and Babies at the World's Fair," with photographs by Jessie Tarbox Beals. These were a set of wonderful pictures and the story was written to accompany them. This was sent out to the press syndicate of newspapers in the United States and was published practically by all the papers in the syndicate. Its success led to her appointment on the staff of the General Press Bureau, and she was the last member to be dropped at the close of the fair. After this she prepared the volume entitled The Art Department Illustrated, describing the pictures and writing sketches of the painters. Mrs. Hutchings has also done much work for The Mirror along the line of art criticisms, municipal improvement work, etc. It is interesting to know that she made inspections in the Industrial School, publishing the facts in that paper which four years later were proven by municipal investigation to be absolutely correct, and the city officials who scored her actions at the time were the first to make apologies when they found her reports to have been verified. For two years she was on the editorial staff of the Valley Magazine, taking the Children's and Domestic Science departments. She prepared about one-half of the first issue of Myerson's American Family Magazine, using seven pen names, and was on the staff for one year. It is necessary for Mrs. Hutchings to be absolutely alone in order to do satisfactory writing; the presence of another in the house is disturbing. She does her best work between nine and twelve in the forenoon, and says writing at night is an utter impossibility. When she gets tired or the sentences do not flow smoothly, she leaves the typewriter, going into the kitchen to make a salad or a mayonnaise dressing, which has oiled the cogs for many a story that was slow in the making. Incidentally Mrs. Hutchings is an excellent cook. She does her own housework, marketing, etc., preferring the occupation of a housewife to the easier, but less private life of a hotel. Many of her articles require a great deal of foraging for material, but she is so persistent that the word "fail" has no place in her vocabulary. Frequently in the search of material for one story she runs across another. An idea will lie dormant in her mind as long as two years, sometimes even longer-when suddenly without warning it will present itself full fledged to be written, and then dropping whatever she may be doing, puts it down just as it comes to her, rarely making any changes. With few alterations her work is sent to the publishers just as first written, attributing this to the fact that all of her good work is the result of subconscious cerebration. She has seen among her clippings articles that she would not believe were her own had she not found her initials at the end. These stories would sometimes require a vast amount of research, but could be dismissed from the memory as quickly as acquired, and again others have impressed themselves on her mind so vividly that she could repeat them almost verbatim. Her memory is unusual, and her mind a storehouse of information. It is, in fact, remarkable-wholly isolated items of information that have been picked up in the course of years, coming up at the time most needed. For her sketches, a paragraph in the newspaper, a chance conversation with an acquaintance, an accidental happening while on a street car, or anything that looks like a plot for a story, is jotted down in a note-book with just enough words to suggest the idea and keep it in her memory. And these notes in the book she might look at forty-nine times and they would mean nothing-but the fiftieth time would suggest the whole story ready to be written out. The manner in which she obtained the material for "The Exile," one of her stories, is fairly typical of her method of work. One morning while engaged in the altogether uninteresting task of washing dishes, her mind was arrested by the sudden call of "rags, bottles, and old iron," in the alley behind the house. Immediately she stopped her work, going into the dining room where she took a pad and pencil and wrote as fast as she could--finished the story and went back to the breakfast dishes, having no definite impression of just how she had arranged the details. The rag-picker's call in the alley had suggested the life of an old Hebrew woman who, in her youth, had gathered rags to support her children. In her old age, and in the home of her wealthy son, she, too, heard the call of the rag-picker in the alley-the call that was the connecting link between her active, happy youth, and the rich desolation of her old age. Trusting to the good nature of the servant she ventured out to the cart only to discover that her friends were dying of pestilence in the little Jerusalem section of the city. In a revulsion of feeling the old woman went back to her room, tore off the beautiful clothes her, son had provided, clad herself in the treasured garments of her young womanhood and went back to her own people. After three days her son discovered her in time to receive her dying message that "the Babylon of his love was still for him, but for her the years of captivity were ended." Mrs. Emily Grant Hutchings is the daughter of Carl H. Schmidt, who was born in Altenburg, Germany, and came to America in 1849, He was a minister in St. Louis in the old Methodist Church on Wash Street. While there he planned to go as a missionary to Japan. His wife studied medicine in the Missouri Medical College in order that she might accompany him and have access to the homes of the natives. Mrs. Schmidt was a pioneer woman physician in the Mississippi Valley. As her husband was transferred from year to year by the conference she would practice medicine where they were stationed. On account of ill-health Mr., Schmidt was obliged to give up his missionary plans and during the Civil War entered the offices of the Hannibal & St. Joseph Railway Company in Hannibal, occupying the position of department secretary until his death in 1884, and Mrs. Schmidt continued to practice medicine until 1904, when she retired, living with her son until her death in 1909 at the age of seventy-nine years Mrs. Hutchings is the youngest of a family of six children--four boys and two girls. Her sister, Mrs. F. W. Arnold, of St. Louis, was for several years the superintendent of the Goldstein Hospital for Surgery of the Head. She took her training at the Baptist Sanitarium' and read medicine with her brother in Hannibal, Dr. Richard Schmidt. Emily Schmidt attended the public schools in Hannibal, where she was born, graduating from the High School at seventeen, and going from there to Germany to a famous school for girls in Altenburg, the birthplace of her father, the Karolinum Hohere Tochtere Schule, where she remained for one year. On coming back to America she entered the State University at Columbia, taking a course in letters. For two years she taught Latin and Greek, also German, in the High School of Hannibal, and then came to St. Louis, taking a position as a feature writer on the St. Louis Republic from August, 1896, until February, 1897, when she married Charles Edwin Hutchings, secretary of the Board of Commissioners of Tower Grove Park. While on a journey from St. Louis to Memphis gathering material for an article for Munsey's Magazine she met Mr. Hutchings. Because she had a story in the June number of McClure's of that year on "Mark Twain," he first became interested in her, and before their return to St. Louis, discovered that they had other tastes in common besides "Mark Twain." Mr. Hutchings was born in Clarinda, Iowa. As a newspaper man he has had a wide experience. For many years he was associated with Dr. Trelease, of Shaw's Garden. All of the photographs his wife uses in her newspaper work are made by Mr. Hutchings, who is an expert photographer. They are a very devoted and congenial couple-their work running along the same lines to a great extent. The home of the Hutchings while it has none of the Bohemian element--is a center for a delightful circle of artistic and literary people. Mrs. Hutchings is often asked for advice by people who want to write, and her inevitable answer is, "Don't!" If it be the thing to do, no amount of discouraging will dissuade those so inclined from it, but it takes a stout heart to stand the disappointments and hardships that this work entails. From her varied experiences Mrs. Hutchings is a very interesting woman; she possesses the rare tact of being a good listener, as well as entertaining in conversation. She has a lovable disposition and is a woman whom all other women admire. - NOTABLE WOMEN OF ST. LOUIS, pp. 110-114. |

Emily Rosalie Schmidt Grant Hutchings died in St. Louis, Missouri on January 18, 1960 at the age of 89. Her death certificate gives her birthdate as January 30, 1870. Her obituary appeared in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch on January 20, 1960. ("Emily Hutchings Funeral Tonight," p. 3B). Much of the information in the obituary was from her biography in Notable Women of St. Louis. The source of her name "Grant" remains a mystery but was perhaps a pseudonym she continued to use throughout her career. Her husband Charles Edwin Hutchings had died in 1955 and she was survived by several nieces and nephews. Her death certificate indicates senility and malnutrition contributed to her death. She was cremated and information online at findagrave.com indicates hers are unclaimed cremains in storage at Valhalla Cemetery in St. Louis, Missouri. In a strange and eerie twist of fate, the website asks anyone interested in claiming the remains to contact them at 314-863-3011.

_____

For further info see:Also see: "Mark Twain and the Ouija Board Lawsuit"

Read

a synopsis of JAP HERRON by Dave Thomson.

|

The New York Times news reports on JAP HERRON and the ouija board lawsuit: September

9, 1917 - BOOK REVIEW - LATEST WORKS OF FICTION - JAP HERRON February 12, 1918 - [Editorial] Annoying, but Not Dangerous. |

More on Patience

Worth and Emily Grant Hutchings at: http://www.prairieghosts.com/pearl.html