Quotations | Newspaper Articles | Special Features | Links

| Search

Mark Twain As His Secretary at Stormfield Remembers Him; Anecdotes of the Author Untold Until Now

By MARY LOUISE HOWDEN

Illustrations by Reginald Birch

The

October glory of the New England hills is a wonderful thing to the stranger

who has been accustomed to the clinging mists and subdued colors of an English

autumn. The Neophyte, stepping from the train at a little wayside station in

Connecticut late one afternoon, caught her breath at the sight of the symphony

in russet and gold with a background of far blue hills that spread itself around

her.

The

October glory of the New England hills is a wonderful thing to the stranger

who has been accustomed to the clinging mists and subdued colors of an English

autumn. The Neophyte, stepping from the train at a little wayside station in

Connecticut late one afternoon, caught her breath at the sight of the symphony

in russet and gold with a background of far blue hills that spread itself around

her.

The neophyte had other things to be breathless over besides the beauty of the scenery. For one thing she was not very old in years and had only been in this land of opportunity four months, so that many things American were new and bewildering to her. Secondly, she was very much a Neophyte as far as the stenography by which she intended to earn her living was concerned, so much so that she had anxiously practiced "speed" on the boat crossing the Atlantic, with the kindly assistance of the girl who had shared her stateroom! Third--and most important and wonderful of all the interesting things that had happened to her in the last few months--she was going to work for one of America's greatest authors, one in whose books she had revelled from childhood.

It had all come about so unexpectedly. The Neophyte, homesick and rather shy, scanning the newspaper columns for a position, had run across of an advertisement calling for a stenographer, "Beginner preferred; experience not necessary; to go to New England."

"I am quite inexperienced," she thought, "I will have to begin at the beginning and work up. Maybe I could get this one."

The words New England attracted her. The Neophyte was steeped in the atmosphere of Kate Douglas Wiggin and Mary F. Wilkins Freeman, and New England to her spelled romance. She composed her letter of application very carefully. The answer to it sent her hurrying to a home on lower Fifth Avenue, New York, there to learn to her utter amazement that she had been selected as stenographer to the world's most famous humorist. And now as the surrey bore her along the winding Connecticut roads and finally climbed the hill on the crest of which Mark Twain had build his new home, she had to pinch herself to make sure she was wide awake.

"There's the home now," said the driver, pointing ahead with his whip. The Neophyte took a long look and caught her breath again. It stood proudly on the very top of the hill, a long, low house, whose white stucco was tinged with pink from the sunset behind her. She thought it the most satisfyingly beautiful place she had ever seen. "It looks almost to peaceful to be called "Stormfield," she thought. The surrey stopped at the door and its occupant was greeted by a hospitably smiling little social secretary. Mr. Clemens, she was told, was out. He had gone for a drive. But would she like to see the house and the place where she was to work? The Neophyte certainly would.

The large rectangular front hall, very simply furnished, was flanked on the right hand by the billiard room with its big table, its dais, its crimson walls and its open fireplace, with a beautiful carved wooden mantel, which had come all the way from Honolulu and had the Hawaiian word "aloha" (welcome) carved on it. To the right of the hall was the living room, which ran the whole width of the house from front to back. It, too, had a huge, hospitable open fireplace, the walls were lined with books, and one wall was almost entirely occupied by the big orchestrelle, which Mr. Clemens like to have played to him of an evening. The author's favorite armchair with smoking apparatus handy, was indicated. Glass doors opened on a loggia just then bathed in sunset light and giving vistas of green, blue and purple hills rolling away to the far horizon.

The dining room, back of the hall and opposite the front door, had French glass doors leading on to a terrace which was supplied with comfortable looking reed chairs and a card table. From the terrace a wild woodland garden descended the hill and lost itself in the woods at the foot.

The Neophyte was taken up-stairs and shown Mark Twain's bedroom with its four windows, each framing a view which was a picture itself. The enormous four poster bed had its snowy covers turned down, so that its occupant could get in whenever he wished. "Mr. Clemens believes in spending much time in bed," she was told. "He sometimes spends the whole morning and does a great deal of his dictating there."

Before leaving the house she was shown the little study to the right of the hall which was to be her own special sanctum. She was asked to inspect the typewriter and see if it were the kind she was accustomed to; if not, another would be procured at once. A glance told her the machine was an old friend. She anticipated no difficulty with it, except from her own shaking fingers. When she tried to express something of this feeling to her guide she was reassured. "Mr. Clemens does not dictate to the machine. You will take stenographic notes, and you need not be afraid. He speaks very slowly."

With this comfort the Neophyte went back to the surrey and was escorted to the farmhouse at the foot of the hill which had been chosen as her abiding place.

All through her stay there it seemed to her that that farmhouse, its occupants and the neighbors might have been lifted bodily from a story, the white painted house with its green shutters, the three Scotch firs in the "dooryard," the steep and rocky fields rising behind it, the bare but spotlessly clean kitchen, the absence of most of the conveniences, the pump in the backyard, the crayon portraits in the parlor, the party telephone that rang every time any one on the line was wanted, a different ring for each subscriber.

"You needn't pay no attention to that," said the farmer's wife genially, when the telephone shrilled insistently during supper. "Our ring is five; that's Mrs. Banks's ring. She lives up the road a piece. Unless, of course," she added, "you want to listen to what she's sayin'!"

"Do you listen in, really?" asked the Neophyte, amused.

"Well, you ain't supposed to, of course," replied her hostess. "But there's a many as does. There'll always be a plenty folk in this world that's better at mindin' other folks' business than their own--and the party line's as good as a newspaper to 'em."

The Neophyte was enchanted.

But for all her delight in her new surroundings she did not sleep well that night. Tossing and turning on a rather hard bed in the up-stairs front room she was a prey to all the fears that had beset her in the train, with some additional ones.

Supposed she couldn't take Mr. Clemens's dictation? Suppose she couldn't read her notes after she had taken them? Suppose she didn't suit?

"I shall be disgraced," she said, addressing the little silver moon that was peeping at her over the top of the smallest fir tree. Then she said a fervent prayer and finally fell asleep. She woke to find the sunlight of a glorious fall morning mellowing the bare walls of her room.

"You look kind of peaked," said the farmer's wife at breakfast. "Guess you didn't sleep any too well--the bed was strange to you."

"I'm nervous--rather," said the Neophyte. "You see," she went on, her need of sympathy impelling her to confidences, "it's the first position I've had over here. And I only learned stenography just before I came over--and he's such a very famous man."

"Well, now," said the good woman heartily, "I wouldn't be one little mite afraid if I was you. Why, Mr. Clemens is a real nice old man, real kind he seems to be, and talks to you just as friendly and ordinary as the next one. He's well liked here. Don't you worry any. Eat a good breakfast now. Don't you want some o' this coffee cake? It's fresh made."

But the Neophyte couldn't. Swallowing a cup of coffee she went up-stairs to put on her hat.

All the way up the hill to Stormfield it seemed as if the rustling of meadow grass, the roar of the waterfall down in the hollow, the twittering of the birds and the shrilling of the locusts were drowned out by the persistent beating of her much perturbed heart.

The butler opened the front door and directed her to go to the study. Mr. Clemens, he said, would be down in about fifteen minutes.

The Neophyte put her hat and sweater in the place indicated. She selected a notebook and sharpened a couple of pencils with meticulous care. Then, hardly knowing what she was doing, she took the cover off the typewriter and began mechanically to clean it, although it was in perfect order and never had been used.

A measured tread sounded in the hall outside and the trembling Neophyte rose to her feet. All her life she had been familiar with pictures of her new employer. But no picture, it seemed to her, had ever done justice to the picturesqueness of the figure appeared in the doorway--the mane of snow white hair, the white suit against the dark background of the hall, the busy eyebrows that gave to the deepest blue eyes a look of fierceness that was belied by the humorous curves of the mouth under the drooping mustache. But there was something else. Mr. Clemens was not a very tall man, yet there was a dignity, a majesty about the figure in the doorway that no picture has ever succeeded in reproducing. For the rest he was ruddy featured, spare and rather rugged of frame--not a superfluous ounce of flesh on him in spite of his seventy-two years--and he was regarding the flustered Neophyte with an expression that was quite kindly. Maybe he wasn't so very terrible after all!

He shook hands gravely and inquired the Neophyte's name. It was given him. He requested to have it written for him. This was done, and he frowned over it while the Neophyte shook. Then he waved the paper on one side and said abruptly:

"You take notes--in shorthand?" The Neophyte admitted that she did.

"Good," he said, his face clearing. "I would like to dictate right now." As the Neophyte sat down and opened her notebook he walked over to the window and stood there. Minutes passed, but no sound came from him. The Neophyte ventured a look. He was standing gazing dreamily out, puffing little clouds from his pipe. Presently he turned and said:

"You've heard of our burglary?" She had--first from the driver coming up from the station; and it had been the mainstay of the conversation at the farmhouse supper the night before.

"Very well," said the humorist. "Now, take this," and he dictated the following:

NOTICE

To the Next Burglar

There is nothing but plated ware in this house now and henceforth.

You will find it in the brass thing in the dining room over in the corner by

the basket of kittens.

If you want the basket put the kittens in the brass thing. Do not make a noise;

it will disturb the family.

You will find rubbers in the front hall by that thing which has the umbrellas

in it--chiffonier, I think they call it, or pergola, or something like that.

Please close the door when you go away! Very truly yours,

S. L. CLEMENS.

Who would take down a think like that and not want to laugh? The Neophyte's shoulders were shaking, but she dared not make a sound. She stole another glance at him. He was still gazing out of the window, not a smile on his face, and speaking in a rather deliberate drawl. Once or twice he took a restless turn or two away from the window, but always returned to it again as if the little study were too restricted for him, as indeed it was. After the first morning he rarely dictated in the study, as there was not enough room to pace up and down, as he liked to do.

He finished the "notice," gave some directions for its typing and its future position on the front door. Then he proceeded to dictate a highly humorous account of the burglary, which account he said was intended for his autobiography. The Neophyte was enjoying herself. She had made a valuable discovery. Mark Twain dictated so slowly, with such long pauses between the sentences that, green beginner as she was, she could take notes with perfect ease and in the pauses could read back and make sure she had not forgotten anything in the previous sentence.

His restlessness increased and the pauses between the sentences became longer. During one of them he strolled out into the hall and vanished for several seconds, leaving the Neophyte in grave doubt as to whether he were finished or not. She was to learn that this was characteristic of him when he was getting tired.

He finished on this occasion by politely hoping he had not given her too much to do! The Neophyte could have laughed aloud at that. T here was so little that it was typed and ready before she went home to lunch. In the afternoon she returned and took from the social secretary her first lesson in handling the mail. She was told that on mornings when Mr. Clemens did not wish to dictate she could attend to the letters instead, and in that case she did not need to return in the afternoon unless Mr. Clemens wanted her.

It was the Neophyte's first introduction to the enormous mass of letters that a famous author receives, and she was at first amazed and appalled by it. There were letters from budding authors who wanted him to read their books, letters from near-poets who wished him to read their poems; letters from people who wanted to invest his money for him; letters from people who objected to his books; letters from people who enjoyed his books; letters from people who wanted copies of his books; letters from people who wanted copies of his photograph, of his autograph; letters from people who wanted everything under the sun. Letters pertinent and impertinent; amusing letters, abusive letters, pathetic letters, and letters that were merely futile and boring. The new stenographer was moved to indignation. "They pester him!" she said to the social secretary.

Mr. Clemens never saw most of it--did not wish to see it. Letters from his daughters, relatives and close friends he read and answered himself, sometimes by hand, sometimes by dictation. Letters from strangers that were more than ordinarily interesting and amusing sometimes got through the barrier. People that required to be tactfully "headed off" were dealt with by the social secretary. The majority of the importunate correspondents received a polite form letter which could be altered a little to suit each particular case. The Neophyte soon learned to handle these. Requests for autographs were taken care of by the simple method of catching the great an when he happened to be in a good humor, seating him in front of a large sheet of paper and having him write his name all over it. These were afterward cut out in little squares and kept in a handy desk drawer ready to be slipped into an envelope when a request came. A request for an autograph was never refused. Autographed photographs were kept on hand in the same way, but were dealt out much more sparingly.

One terrible day--terrible because of her feeling when she found out what she had done--the Neophyte let an effusion in vers libre from an utterly unheard of poet "get through" to Mr. Clemens. He dictated in bed that morning, and when she entered the room he had the verses in his hand and was reading them with an expression of intense boredom. She shook in her shoes waiting for a storm, which, however, never came. He dropped the manuscript wearily on the counterpane and lit his pipe. After a few soothing puffs he flicked the offending papers on one side and remarked gently and meditatively:

"We know God made this poet, but we don't know what He did it for!"

He dictated in bed many mornings and made as complete a picture there, with his leonine head outlined against the enormous mahogany four-poster, as he did everywhere else. In bed he could not escape when she produced her unfailing sheet of paper with a request for many autographs. The whimsical patience with which he granted the request always surprised her a little. It was touching, too. There was a sort of pathetic patience about him at times as if he found the penalties of fame very burdensome but knew that nothing could be done about it.

On other mornings the dictation took place in the billiard room. The Neophyte, sitting on the dais with pencil poised over her notebook, used to watch with keenest appreciation the white figure contrasted against the crimson walls of the billiard room--pacing, pacing restlessly. Sometimes there were four or five minute pauses between sentences. But the phrase when it came was always perfectly formed.

He put in the punctuation himself. His stenographer was never allowed to add so much as a comma. His humor was a delight, but the Neophyte from the beginning rigidly suppressed her tendency to immoderate mirth. It required considerable self control at times to keep from spluttering.

Mark Twain's gravity in dictating was a continual surprise to her. "He doesn't seem to think he's funny," she said to herself. A slightly heightened and more deliberate drawl was the only indication that something more than usually delightful was about to fall from him. The dictations were all too short for her. She would have liked much more of them. But there were mornings when he would detain her only about fifteen minutes. Then he would say with a twinkle, "Well, I guess I've done enough work for today." And in a few minutes he would be heard outside whistling like a school boy.

The typewritten manuscript she left on the study table when she went home to lunch. Mr. Clemens would find it and look it over at his leisure. If he had criticisms or corrections to make he wrote little notes and left them on the typewriter where she could find them next morning.

He was not a distinctively humorous person in his every-day life. To the Neophyte he was always rather a tragic figure, lonely in his fame. To a casual observer he seemed just a kindly, gentle, rather sad old man with a courteous Old World dignity all his own. Outside of his dictation his flashes of spontaneous wit were only for those he liked best. Irritable he could be, furious he could certainly become; but is courtesy and consideration for those who served him made it a pleasure to work for him.

The Neophyte had been raised on a farm and liked animals. Stormfield did not boast a dog, but cats there were in plenty, also kittens, and they were all over the place. Mark Twain was very fond of them and would stop dictating to pick up a kitten and pet it. Luckily the Neophyte shared his taste and it did not disturb her to take dictation with one furry intruder on her lap and another parked beside her notebook or on her shoulder.

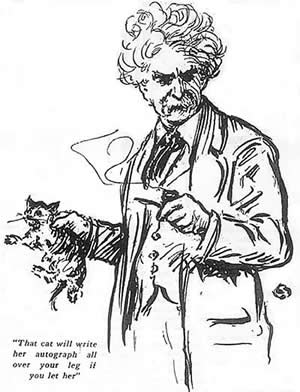

There was one exception, and that was a meowing, clawing little tabby who rejoiced in the name of Anastasia. She was not a favorite with Mr. Clemens or any one else; but it was Anastasia who broke the ice between the Neophyte and her employer some two weeks after the Neophyte's arrival, when the latter was still too much in awe of him to be quite natural in his presence. This came about on a day when Anastasia persistently intruded herself on the dictation and instead of jumping on the Neophyte's lap as the other cats did, she climbed, using all her claws to do it with and sticking them into whatever portions of the Neophyte's anatomy presented the best foothold. In the pauses the harassed stenographer wold detach the persistent little beast and deposit her firmly on the floor, but it was no use--Anastasia climbed right up again, selecting the shoulder as her objective.

The October weather was unusually warm, and the Neophyte, in a thin organdie dress, was ill protected from sharp little claws. She was beginning to feel that she had endured it as long as she possibly could when Mr. Clemens's hand suddenly descended over her shoulder. He seized the clinging, clawing kitten by the back of its neck and dropped it, spitting and sprawling, on the grass outside the window. Then for the first time the eyes of the Neophyte and Mark Twain met--and there was a humorous twinkle in both.

"That cat," commented Mr. Clemens, "will write her autograph all over your leg if you let her."

There were many free afternoons which the Neophyte spent tramping through the gloriously colored Connecticut woods, and when the weather became wintry, in flying wildly down the snow-covered hillsides in a careening bob-sled steered by the farmer's thirteen-year-old daughter; or browsing over a Mark Twain volume before the glowing stove in the farmhouse parlor. If Mr. Clemens was seized with an inspiration in the afternoon he never telephoned for her, as he was supposed to do, but wrote out what he had to say in longhand and left it on the study table to be typewritten next day.

On the few occasions on which this happened the Neophyte was conscience-stricken and would spend two or three succeeding afternoons at Stormfield on the chance that she might be wanted. But she generally drew a blank. Mr. Clemens preferred to go for drives or play billiards in the afternoon. But on at least two such afternoons she stayed late and counted herself in luck, though she did not catch a glimpse of any of the household. She sat on the stairs in the gathering winter twilight, thrilled to the very marrow by the harmonies that poured through the house--harmonies interpreted by a master hand. Ossip Gabrilowitsch, who afterward became Mark Twain's son-in-law, was spending the week end. The glorious sounds would stop for a while and Mr. Clemens's sonorously clear voice could be heard reading some passages from "Tom Sawyer." Afterward the cataract of melody would fill the house again. These two masters of technique, each in his own line, were entertaining each other. It was an entertainment an outsider would have given many dollars to hear. And the little outsider sitting curled up on the dark staircase shivered with sheer bliss.

That was a red letter day. Another was when Mr. Clemens gave the address at the formal opening of the new little library in Redding, for which he had donated most of the books. If it is possible to be ill through sheer unadulterated enjoyment, the Neophyte came very near being incapacitated that day. As most of his audience were farmers, Mark Twain began by telling them how he adored farming. That year, of course, he hadn't done much, the bananas hadn't ripened and he hadn't planted very much sugar cane. But next year, why they should see what he would do.

He went on to tell them how in the day of his youth he had once edited an agricultural paper for a short time--for a very short time. The day the paper first came out under guidance people were sitting on the office railings and crowding up the stairs to catch a glimpse of the man who was doing the editing. The editorial page was devoted to turnips. Millions of turnips, it declared, were spoiled every year by being picked before they were ripe. The proper way to do was to send a boy up to shake the tree.

When the real editor for whom Mark Twain had been substituting returned he was annoyed about it and remonstrated vigorously. But Mark Twain told him that any fool would have known he meant to say "shake the vine," of course. However, the editor took exception to his remarks anent "the molting season for cows" and he had to resign. But he felt sure that he could have sent the circulation of that paper up by leaps and bounds if he had been allowed to stay with it!

The faces of his audience were a study at first. None of them had ever had the privilege of hearing the king of humorists before. Most of them were elderly country people with all the New England taciturnity and dislike of giving themselves away, and Mark Twain's drawling speech and gravity, his inimitable way of apparently not considering himself funny, puzzled them at the outset. But long before he got through they were rocking with delight.

The Neophyte did not need to draw on the Redding library for books. She could revel to her heart's content in the well stocked book shelves that lined the living room at Stormfield, and borrow any book she pleased therefrom.

Mr. Clemens's favorite books were not to be found there. They were kept in his room, some of them beside his bed. The "Memoirs" of St. Simon were there, Carlyle's "French Revolution" and "Pepys's Diary." His reading covered an extremely wide range, but he was especially fond of biography and letters. It was his habit to make copious annotations on the margin of his favorite books, and these comments were sometimes caustic to a degree, but always illuminating. Lying in bed he wold read and read, sometimes pausing to jot down his ideas on the margin and smoke copiously and constantly. Or, dictating, he would lie back against the pillows with his eyes half shut, blowing clouds of smoke and weaving a fabric of the most delicate fantasy, or speaking vividly of men and deeds of by-gone days. He seemed to ponder each sentence before uttering it, but whatever it was--sometimes humorous, sometimes cynical, sometimes deeply and cuttingly sarcastic--it was always of absorbing interest. He was building up his autobiography for posthumous publication.

The Neophyte learned among other things that Stormfield had originally been called "Innocence at Home," but that this was changed because Mr. Clemens said the task of providing enough innocence to justify the name fell entirely upon him and proved a burden beyond his strength. None of the other members of the family had any!

One day shortly before Christmas the Neophyte, wading through a mass of quite uninteresting mail, came upon a letter which caused her to gurgle with mirth. It was from Mr. Robert Collier, of "Collier's Weekly," and stated that he had been hunting for a unique Christmas present for Mr. Clemens, something really novel that he did not already have and wouldn't be likely to get from anybody else, and had hit on a young elephant as most likely to fill the bill. He had, therefore, procured one, and it would be along as soon as he could get a freight car for it; also the loan of an elephant trainer form Barnum & Bailey's winter quarters at Bridgeport.

The Neophyte was not from Missouri, but it appeared to her that nobody would take this very seriously. Mr. Collier's letters always went to Mr. Clemens; they were intimate friends, but the Neophyte carried this first to the social secretary, who happened to be in bed with a headache, thinking she would enjoy the joke.

That lady, on reading it, dropped back on the pillows and indulged in what appeared to be a near-apoplectic fit. The Neophyte expressed her conviction that the whole thing was a joke. But the social secretary gave her to understand that she knew Mr. Collier all too well; that he was a man of his word, and if he asserted that an elephant was forthcoming an elephant undoubtedly would arrive. "And where," she asked tragically, "are we going to keep it? You know, the pony's in the garage--and how are we to feed it? Oh, this must be stopped!"

And, arising, she donned a kimono and staggered to the telephone. The Neophyte was privileged to listen to a one-sided conversation, in which the timid diplomacy of the secretary was overwhelmed by the apparent cheery optimism of Mr. Collier at the other end. He seemed to have no idea but that his gift would be most welcome an suitable and easily taken care of. The secretary gave it up and went back to bed.

From then on telegrams kept coming from Mr. Collier, messages pertaining to the difficulty of obtaining a car for the elephant. The New York, New Haven & Hartford Railroad was apparently not accustomed to the transportation of elephants. With each message hope rose and fell in the breasts of the Stormfield authorities. Mr. Clemens was saved from worry by being carefully told nothing about it; which the Neophyte felt to be a mistake. A week before Christmas a jubilant telegram arrived from Mr. Collier to say that the car and trainer had been secured, and gloom reigned supreme at Stormfield. Two days before the holiday a load of provisions arrived, according to Mr. Collier's promise; bales of hay there were, and baskets of apples and bushels of carrots. All this was stored in the garage, to the deep interest of the pony.

The Neophyte was due to spend Christmas with friends in East Orange, and felt regretful that she would not be present at the denounement. She made Bessie, the farmer's little girl, who drove her to the station, promise faithfully that she would tell her how things came out.

Two days later, when Bessie met her at the station, she could talk of nothing else, and from her account, from what she heard at Stormfield and from the highly spiced account which Mark Twain dictated for his autobiography she had no difficulty in envisaging the climax of the joke. On Christmas morning, it appeared, the Stormfield telephone rang. It was a message from the station agent, who said that there was a man at the station claiming to be a trainer from Barnum & Bailey's, who had been sent to take care of an elephant for Mr. Clemens. Should he bring him up? By all means. So the man was brought up. He was received by the social secretary, also the financial secretary, who had come out from New York for the occasion; and he solemnly instructed them in the art of entertaining an elephant, told them what the animal liked to eat, how to treat him when he was ill, and which end of him to avoid when he was angry, etc.

Then he departed and the elephant arrived. It needed not a trainer, nor did it need the provisions stored in the garage, and it couldn't have given the most timid secretary nervous prostration. For it was only about three feet high, built of cloth and went on wheels. The "trainer" was Robert Collier's butler in disguise.

The pony comes out on top in this joke," remarked Mr. Clemens. "She gets the bales of hay and the carrots and the rest of the provender."

The Neophyte's chief feeling during the year that she spent at Stormfield was that there was so pitifully little she could do for the humorist. Watching him she often sensed the tragedy in the life of the man who made fun for the whole world. Deprived by death of those he had loved best, much separated by circumstances from the other members of his family, and dependent upon paid help, he appeared, for all his fame, a somewhat sad and lonely figure. He could be gay at time, he could be funny; he was always intensely alive, interested in the things of the moment, but there were depths of sadness in him which welled up frequently.

There was a difference between Mark Twain and his books. The public saw the humorist, but only those who were privileged to be much with him knew the dignity and seriousness and depth of the man.

Those who know only "Tom Sawyer," and "Huckleberry Finn" and "The Innocents Abroad" do not know Mark Twain. He was very versatile. "Joan of Arc" contains depths of pathos and tenderness not reached in his other books, and it was his own favorite brain child. In moments of anger or of deep sorrow he would find relief in writing, and it was to one of the latter moments that the world owes one of the most tenderly beautiful and heartrending things that ever was written--"The Death of Jean."

On Christmas Eve of 1909 the Neophyte waiting for a suburban train in a New York terminal, picked up a newspaper and read of the death of Jean Clemens. Jean had come home to be her father's secretary after the Neophyte's departure for Florida. She was the only one of his family left him in his old age, for his daughter Clara had married Ossip Gabrilowitsch a few months before and had gone with her husband to Europe. Jean had been found dead of heart failure in her bathtub on the morning before Christmas. And the thought of that lonely old man in that big house, surrounded by preparations for Christmas festivities, with the dead body of his daughter lying upstairs, was too much for the Neophyte. The tears flowed down her cheeks as she cried openly and unashamed there in the terminal and heeded not the curious looks of homebound commuters.

Mr. Clemens eased the pain in his heart by putting the account of Jean's death down on paper and when he had finished he said, "I shall never write any more." It was his swan song, and when, four months later, the Neophyte heard that the end had come she could not but be glad for him. Mark Twain had coveted death. He had reached the zenith of his fame. His heart was buried in the graves of those whom he had loved so faithfully, and the world could give him nothing that he wanted any more. And those who knew the man and cared for him could only be thankful that he had got his wish in spite of their own sorrow.

It was an irreparable loss to the world, for if Mark Twain had only lived ten or fifteen years longer, through one of the greatest epochs in the world's history, what could he not have given us? Those who knew him can imagine the brilliancy, the incisiveness, the scathing sarcasm and wrath that would have flowed from his pen during the World War. Mark Twain hated hypocrisy, oppression, brutality and injustice. He was always on the side of the under dog.

His pronouncements on prohibition as it is conceived and enforced in these United States would have been well worth hearing, and what would Mark Twain have said to radio--that wonder child of the present day? Would he have been a "broadcaster"--he whose fame had already been broadcast to the ends of the earth?

It is not given to everybody to have the privilege of association with such a man. Such good fortune does not happen twice in a lifetime, and for the privilege and the happy memories it has left behind it the Neophyte can only say "Deo gratias."

Related article in Newark Evening News

Return to The New York Times

index

Quotations | Newspaper Articles | Special Features | Links

| Search