|

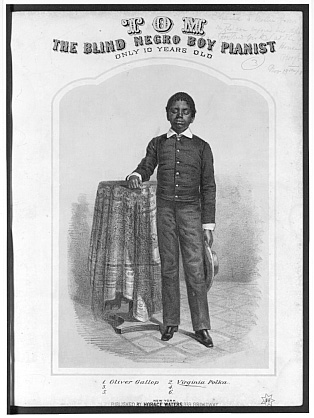

Safely tucked away in a few scattered archives across the nation are pages of sheet music--compositions with titles such as "Battle of Manassas" and "Virginia Polka" that are dormant testimony to the life of the child named Tom who composed them--a child who lived a century past and whose musical abilities still remain a medical and scientific mystery. One common thread of explanation found in all attempts to explain Tom by those who witnessed his performances is that he embodied the spirit of a higher power. Tom was born on May 25, 1849 with a condition that today's doctors might diagnose with the politically correct term "autistic savant"--one of only about 100 cases recorded in medical history. Tom's father Domingo Wiggins, a field slave, and his mother Charity Greene were purchased at auction by James Bethune of Columbus, Georgia when Tom was an infant. Domingo and Charity's former master thought the blind sickly "pickaninny" had no labor potential and he was thrown into the sale as a no cost extra. Although Tom's parents were married, the prevailing custom of the time dictated that female slaves and their children retain the names of their owners. Following slavery tradition, Tom received the name Thomas Greene Bethune. |

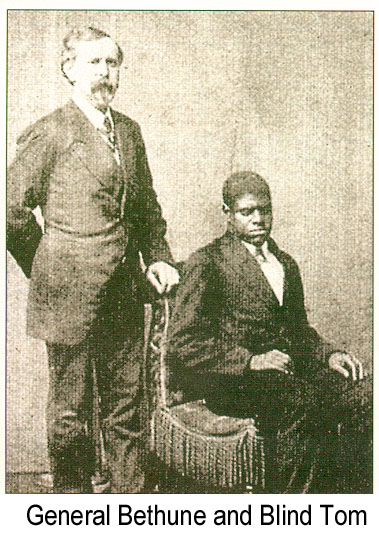

Some accounts of James Bethune accord him the salutary title of Colonel; others, General. However, according to Bethune family member Patti Andrews, Bethune held the military rank of Lieutenant in the Lawhons County, Georgia Volunteers. Bethune was a veteran of the Indian Wars, a practicing lawyer and a newspaper editor at the Columbus Times. He later published his own secessionist newspaper called the Cornerstone--one of the first publications to advocate secession for the South.

For the first several years of his life, Tom's only sign of human intelligence was his interest in sounds--any sound--and an uncanny ability to mimic them. Charity was allowed to bring Tom with her to the main house where she worked for the Bethune family--a family of seven musically talented children who overflowed their home with singing and piano playing. When the Bethune children practiced their piano lessons, Tom listened. Once given access to the keyboard by himself, Tom astounded the family--his small hands and fingers able to reproduce the sequence of chords from his memory exactly as he had heard them played. General Bethune told Charity that her son had as much intelligence as the family dog and he began teaching Tom to respond to animal commands like "sit" and "stand." Members of the Bethune family delighted in teaching their family pet the names of objects that he could feel and smell.

By age of six Tom started improvising on the piano and creating his own musical compositions. He claimed the wind, or the rain, or the birds had taught him the melody. Even though a local music teacher told Bethune that Tom's musical abilities were beyond comprehension and his best course of action was simply to let him hear fine playing, Bethune provided Tom with various music instructors. One of Tom's music teachers later reported that Tom could learn skills in a few hours that required other musicians years to perfect. In October 1857, General Bethune rented a concert hall in Columbus and for the first time "Blind Tom" performed before a large audience that had difficulty comprehending how a blind idiotic slave child could master the piano keyboard.

Slaves with musical talent meant income for their owners and in 1858 James Bethune "hired out" Tom to concert promoter Perry Oliver for a period of several years. It has been estimated that Bethune pocketed $15,000 from the arranagement and that Perry Oliver made profits amounting to $50,000. Tom, now age nine, was separated from his family and exhibited throughout hundreds of cities on a rigorous four-shows-per-day schedule.

Not only could Tom perform world classics, he would astound his audiences by turning his back to the piano and giving an exact repetition--a reversal of the keys the left and right hands played. Musicians in the audience were invited to challenge Tom to a musical duel. Tom could successfully reproduce on the keyboard any piece of music a challenger would first perform. And taking that feat one step further--Tom could play a perfect bass accompaniment to the treble played by someone seated beside him--heard for the first time as he played it. Tom would often push the other performer aside and repeat the entire composition alone. When audiences applauded, Tom followed suit--mimicking the sounds of approval.

One of the earliest concert reviews published in the Baltimore Sun on June 27, 1860 announced to its readers that Tom was a phenomenon in the musical world--"thrusting all our conceptions of the science to the wall and informing us that there is a musical world of which we know nothing." A command performance before President Buchanan at the White House drew further attention and the press referred to him as the greatest pianist of the age whose skills surpassed Mozart.

Several months later, in January 1861, Civil War was becoming a widespread reality. Perry Oliver and Tom were in New York when news broke of Georgia's secession from the Union. Canceling further New York engagements, Perry Oliver and Tom beat a hasty retreat from the land of abolitionists. Tom's talents would be used in the South giving concerts for Confederate soldiers and raising money for the Southern cause.

After the Battle of Manassas, Tom and his manager were confined in Nashville for several months and every newspaper account of the battle was discussed in detail for days on end. After hearing the battle discussed for several weeks, Tom sat down at the piano and produced a composition incorporating melodies representing the Union Army, the Confederate Army, and Confederate and Union leaders Beauregard and McDowell. The composition became a popular signature piece and a favorite with concert audiences in the South. One surviving account of his performance at Camp Magnum appeared in the North Carolina Fayetteville Observer for May 19, 1862:

"The blind negro Tom has been performing here to a crowded house....He performs many pieces of his own conception-- one, his "Battle of Manassas," may be called picturesque and sublime, a true conception of unaided, blind musical genius.... This poor blind boy is cursed with but little of human nature; he seems to be an unconscious agent acting as he is acted on, and his mind a vacant receptacle where Nature's stores her jewels to recall them at her pleasure."

General Bethune's sons enlisted in the Confederate army and in 1862 the General himself took up managing and traveling with Tom--always attempting to keep far south of the Union army lines and out of the line of fire. Word of Blind Tom was kept alive in the North by noted writers such as Rebecca Harding Davis who tantalized readers of the prestigious Atlantic Monthly with a report of Tom's abilities. Davis reported a childishness about Tom that required coaxing and promises of cake and candy before he would perform; she also noted, "Some beautiful caged spirit, one could not but know, struggled for breath under that brutal form and idiotic brain."

Foreseeing that the South would

soon fall to Union domination, General Bethune arranged for Domingo and Charity

to sign a contract giving him management of Tom until he reached the age of

twenty-one. Tom would receive food, shelter, musical instruction and an allowance

of $20 a month. The surviving parents were to receive $500 a year plus food

and shelter. Bethune would retain over ninety percent of the remaining profits

from Tom's performances-- conservative estimates place that amount at $18,000

a year.

Foreseeing that the South would

soon fall to Union domination, General Bethune arranged for Domingo and Charity

to sign a contract giving him management of Tom until he reached the age of

twenty-one. Tom would receive food, shelter, musical instruction and an allowance

of $20 a month. The surviving parents were to receive $500 a year plus food

and shelter. Bethune would retain over ninety percent of the remaining profits

from Tom's performances-- conservative estimates place that amount at $18,000

a year.

After the War's end, Tom, who never knew he was free because he had never actually known he was a Negro slave, was launched upon another tour which included appearances in major cities of the Northern states. One of the first in New Albany, Indiana sparked a monumental news event. Tabbs Gross, an entertainment promoter sometimes described as the nation's black P. T. Barnum, came forward claiming Bethune had accepted his down payment toward an agreed upon $20,000 in gold for possession of Blind Tom. He further claimed Bethune later changed his mind without returning his full down payment. The Bethune entourage, with Tom in tow, hastily exited New Albany and fled to Ohio.

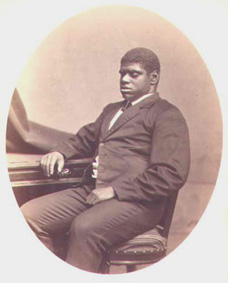

Tabbs Gross and his lawyer pursued the Bethunes into Ohio and the civil case for ownership of Blind Tom's services came to court in Cincinnati with a flurry of newspaper attention lasting well over a week during July 1865. Medical examiners who interviewed sixteen year old Tom reported that he was extremely emotional and "might become combative if taken from those who were then treating him so kindly." When the examiners asked Tom how he as able to play so well, he only responded "God taught Tom." In this case of a black man pitted against a white man for possession of a Negro youngster, the judge rendered the decision in favor of Bethune. Newspaper coverage from far and wide concerning the case provided a wildfire of publicity and fanned the flames of public desire to see "Blind Tom."

In 1869 Tom's path crossed that of Mark Twain who was traveling across the country on his own lecture tour. Twain, who was also writing for the San Francisco Alta California newspaper, reported that he attended Tom's concert three nights in succession. From Mark Twain's first hand account of Tom's performance:

"He lorded it over the emotions of his audience like an autocrat. He swept them like a storm, with his battle-pieces; he lulled them to rest again with melodies as tender as those we hear in dreams; he gladdened them with others that rippled through the charmed air as happily and cheerily as the riot the linnets make in California woods; and now and then he threw in queer imitations of the tuning of discordant harps and fiddles, and the groaning and wheezing of bag-pipes, that sent the rapt silence into tempests of laughter. And every time the audience applauded when a piece was finished, this happy innocent joined in and clapped his hands, too, and with vigorous emphasis."

Twain concluded his impressions of Blind Tom by writing:

"Some archangel, cast out of upper Heaven like another Satan, inhabits this coarse casket; and he comforts himself and makes his prison beautiful with thoughts and dreams and memories of another time... It is not Blind Tom that does these wonderful things and plays this wonderful music--it is the other party."

In 1875, Twain again spoke of Tom's uncanny abilities in a humorous speech he made on the art of spelling. The text of Twain's speech appeared in the Hartford Courant May 13, 1875 and cites Twain as quipping:

Now there is Blind Tom, the musical prodigy. He always spells a word according to the sound that is carried to his ear. And he is an enthusiast in orthography. When you give him a word, he shouts it out--puts all his soul into it. I once heard him called upon to spell orangutang before an audience. He said, "O, r-a-n-g, orang, g-e-r, ger, oranger, t-a-n-g, tang, orangger tang!" Now a body can respect an orangutang that spells his name in a vigorous way like that.

Twain maintained an ongoing interest in Blind Tom's abilities. His personal notebooks reflect occasional entries of the words "Blind Tom" indicating that he may have planned to see more of Tom's performances whenever the opportunity arose. In book editor Henry Holt's autobiography titled Garrulities of an Octogenarian Editor (published by Houghton Mifflin Co., 1923) Holt recalled being with Twain one day in Washington DC in 1885:

The afternoon of that day in Washington was drizzly, and he and I took a constitutional under the same umbrella. He was most of the time talking about Blind Tom, a famous half-idiotic Negro pianist of those days. Mark said he never missed an opportunity to hear him. Tom, it appears, used to soliloquize about himself and his music, and Mark's memory was full of his quaint sayings, of which Mark poured out a stream to me, and so vividly that I can't tell today whether I ever saw and heard Tom, or whether my imagination has constructed him from Mark's account.

Twain again wrote about Blind Tom in 1897. In Chapter Two of Following the Equator, the book that documented Twain's around the world journey, he wrote:

The talk passed from the boomerang to dreams - usually a fruitful subject, afloat or ashore - but this time the output was poor. Then it passed to instances of extraordinary memory - with better results. Blind Tom, the negro pianist, was spoken of, and it was said that he could accurately play any piece of music, howsoever long and difficult, after hearing it once; and that six months later he could accurately play it again, without having touched it in the interval.

Upon Tom's twenty-first birthday and end

of his indentured contract, General Bethune played another legal trump card

and requested that the courts declare Tom legally insane and appoint himself

as legal guardian. The courts complied. Tom continued to perform. Throughout

his life Blind Tom would tour Great Britain, Scotland, Europe, Canada, the Rocky

Mountain states, the far West, and South America. His repertoire included up

to 7,000 pieces with approximately 100 of his own composition and he had added

the coronet, French horn, and flute to his list of mastered instruments. His

life consisted of concert stages, hotel rooms, and train rides. Tom's social

graces remained undeveloped. He usually ate his meals in seclusion and required

assistance in dressing before appearing onstage before his audiences.

Upon Tom's twenty-first birthday and end

of his indentured contract, General Bethune played another legal trump card

and requested that the courts declare Tom legally insane and appoint himself

as legal guardian. The courts complied. Tom continued to perform. Throughout

his life Blind Tom would tour Great Britain, Scotland, Europe, Canada, the Rocky

Mountain states, the far West, and South America. His repertoire included up

to 7,000 pieces with approximately 100 of his own composition and he had added

the coronet, French horn, and flute to his list of mastered instruments. His

life consisted of concert stages, hotel rooms, and train rides. Tom's social

graces remained undeveloped. He usually ate his meals in seclusion and required

assistance in dressing before appearing onstage before his audiences.

Shortly after the Civil War ended, General Bethune relocated the family to a 420 acre estate called Elway about three miles outside of Warrenton,Virginia. Tom was provided with a room containing his own Steinway concert grand piano. For the next twenty years Tom spent the summers between concert tours on the Virginia estate often in the company of the Bethune grandchildren.

Tom loved the Virginia farm life at Elway. He was happiest dressed in simple trousers and a flannel undershirt which were more comforting to him than his formal performance dress. Daily sounds of farm machinery brought him pleasure. After one trip to the fields riding in a buggy behind a reaper, he returned to the house and composed a piece titled "The Reaper" which he dedicated to one of the Bethune grandsons. However, much of the time Tom continued to exist in his own private dream world where he held long and audible conversations with imaginary characters invisible to those around him.

Septembers on the farm always signaled the return of the concert season and the appearance of Tom's concert manager. Tom, who had learned his share of profanity, often threatened never to be taken from Elway again. His protests of "Tell him to go to hell--Tom ain't coming!" would be followed by much cajoling and flattery until he was once again on the road. John Bethune, the oldest son of the family and Tom's former childhood playmate, often traveled with Tom who was distrustful of strangers and prone to temper tantrums unless he believed he was getting his own way. During the times they weren't on the road, John and Tom lived in New York City where Tom continued to receive professional instruction to enlarge his musical repertoire.

In a move foreshadowing change in Tom's life, John Bethune married Eliza Stutzbach, the owner of the boardinghouse in New York where he and Tom were living. The marriage itself lasted only a short time before Eliza sued for divorce claiming John Bethune had deserted her. The marriage ended, not in a courtroom, but with John's accidental death.

In February of 1884, while hurrying to board a moving train, John Bethune was accidentally caught beneath the wheels of the train and dragged to his death. A few months later, a reading of John's will revealed he had banned Eliza from receiving any inheritance claiming she was a "heartless adventuress who sought to absorb his estate." Management of Blind Tom reverted back to the old General. In retaliation, Eliza engineered an alliance with Tom's elderly mother Charity to gain custody of Tom. The custody case dragged through the courts for several years as Charity pursued legal remedies to have control of Tom's life placed in Eliza's hands.

In contrast to Mark Twain's description of Tom as an archangel cast from heaven is The New York Times characterization of the old General as Satan incarnate. In a July 1887 news report The New York Times recorded his appearance in court:

"He is a remarkably well preserved old man with long white hair and beard. He refused a fan offered him as well as a glass of water, and for his comfort pulled out an old-time looking pipe, which he filled with plug tobacco, lit and puffed away as if the thermometer was in the forties instead of the nineties."

On July 30, 1887, a federal court ordered General Bethune to surrender Tom at Arlington, Virginia into the hands of Charity and his former daughter-in-law Eliza Bethune. Newspapers reported Tom, disappointed and grief stricken at the thought of having to leave Virginia and the old General, was threatening to "fight them all."

On the date of surrender, General Bethune's son James brought Tom to the court room. The family who had made a fortune estimated at $750,000 at the hands of Blind Tom gave possession of him over to his mother Charity--a mother he hardly knew. Tom, who brought with him nothing more than his wardrobe and a silver flute, offered no resistance when he boarded the train to leave Virginia for New York and a home with Eliza. However, the word "lawyer" had become a bugaboo for Tom who had never really understood what the word meant but now associated it with men who caused big troubles and things unpleasant.

One month later, Tom was again on the concert stage showing no signs of emotional trauma from his latest custody battle. Now a source of income for Eliza who promoted him as "the last slave set free by order of the Supreme Court of the United States," Tom's performances continued throughout the United States and Canada. He now performed under his father's surname as Thomas Greene Wiggins. With the exception of his brief reunion with Charity who soon returned to Georgia, nothing else had changed. Tom spent the remainder of his life in the care of Eliza. Performances, concerts and vaudeville acts continued until 1904. His last days were spent in seclusion playing the piano and holding imaginary receptions. Tom died at age fifty-nine on June 13, 1908 at Eliza's home in Hoboken. A few days later The New York Times headline read "BLIND TOM, PIANIST, DIES OF A STROKE -- A CHILD ALL HIS LIFE." Newspaper coverage reported that Eliza laid Tom to rest in Evergreens Cemetery in Brooklyn, New York.

Noted Kentucky newspaper editor Henry Watterson wrote one of the most touching tributes to Tom after the wires spread the news of his demise. "What was he? Whence came he, and wherefore? That there was a soul there, be sure, imprisoned, chained in that little black bosom, released at last."

Mystery surrounds Blind Tom's final resting place. Go to "Where is Blind Tom Buried?"

More Blind Tom Links and Resources: