Home | Quotations | Newspaper Articles | Special Features | Links | Search

Home | Quotations |

Newspaper Articles | Special Features | Links

| Search

From: Collier's, vol. 45, no. 8, 1910, pages 42-44.

|

It was on an afternoon in February 1906, that I had my first appointment to meet Mark Twain and make arrangements for sittings for a portrait which I was to paint of him. At that time he lived in the old-fashioned red-brick house on the corner of Ninth Street and Fifth Avenue, the one he occupied up to the time that he moved to Stormfield. Promptly at the appointed time I called, and passing through a hall filled on either side with book-cases, I was ushered into a long, high-ceilinged front parlor so characteristic of the older New York houses. Book-cases here filled all sides of the room, and, with a hasty glance, I noticed Macaulay's "England," Gibbon's "Rome," and Carlyle's works. Two large pictures also attracted my attention; one of him painted in Italy and Alexander's charming decorative representation of the unfortunate Jean Clemens. I had little time for observing more, for, on looking through the open folding doors, and which led to a cozy sitting-room, I caught my first sight of the venerable author who had but a few months before passed his seventieth milestone. |

|

How different, in most cases, are the impressions that photographs and portraits give from those received when we stand face to face with the original! How unlike were all the pictures which I had seen of him. At that time he still wore his black clothes, and his entire head seemed strikingly pale. Instead of the rugged, weather-beaten face which I had expected, I saw one softer and calmer, but no less strong, while the delicacy and refinement of his features were most noticeable. His hair, too, which I had always though wiry, was glossy and silken. Never have I seen a head where it seemed more an integral part--its ivory-like tones melting imperceptibly into the lighter hues of the skin, so that the line of juncture was almost entirely lost. Even his hands betrayed a more actively nervous man than one would be led to imagine a former river-pilot could be. In build he was smaller and slighter than he appeared in most pictures, though it probably was the massiveness of his head that gave this appearance.

On hearing me in the other room, and without waiting for me to be announced, he got up from a long sofa which was placed crossways in a bay window, and removing a pair of steel spectacles, he wrinkled his bushy white eyebrows until his eyes were almost lost, and came forward with a short "How d'ye do?"

My heart fell: so here was America's humorist; how glum, how severe! But scarcely had I time to record these impressions than the eyebrows relaxed, and beginning at the corner of his deep-set eyes, a smile, no, not a smile, but rather a soft reflection of one, illumined his face; and underneath the glow of kindly sweetness could be seen the touch of sadness.

"So you have come here to do me, my boy; come in and sit down: I have been done before," he added, "in many ways, and I have also had some portraits painted, though each one I vowed would be the last; and as I don't believe any one's word should be broken in at least ten years, I guess you will really be the last one to do it. Wait until you look around, and I think you will agree that I am perfectly preserved--in oil, at least."

Reminiscences

Before deciding upon a suitable place to paint, we talked. He had seen a portrait of an actor which I had painted recently, so we, or rather he, talked of the stage and his one excursion into dramatic literature, "The Gilded Age." Getting up from the sofa and clasping his hands behind his back, he walked up and down the room, recalling scenes of thirty or more years ago, and stopping in front of the marble mantel now and then while he emphasized some especial point.

"They thought they could kill it," he began; "the morning after the first performance all the critics damned it--not a word in its favor; the second night we had hardly a handful of people." Up to this point there was resentment in his voice. The plaint of the unappreciated was heard, but suddenly changing his tone, he went on, the smile again beginning to break.

"I grew anxious for my personal safety. But the third night there were almost two handfuls and several laughs, and at the end of the second week those of our friends who had not lent a willing hand had to pay for their seats. Yes, if you have something to say, say it often enough and folks will be bound to listen." Suddenly remembering what I was there for, he said: "But this isn't painting the portrait; we have work to do, both of us." And so he took me from one room to the other, pointing out cherished tokens and mementoes.

Into the dining-room with its colonial furniture and a portrait of himself painted years ago by Frank Millet. "It's all mine, except the hair," he remarked. I looked in bewilderment. "It was this way," he explained, "when I started sitting for that one, my hair was fairly long, but as the sittings continued, it grew until it was uncomfortable. So one day, without saying anything to Millet about it, I went to the barber to have it trimmed. Unfortunately, I grew sleepy in the comfortable chair, and when I woke up I saw that I had lost all likeness to my portrait. I didn't know what to do, for I was afraid of Millet in those days, so on the day for the next sitting I hired a wig and went to the studio. When I got there Millet at once noticed how fine my hair looked and painted it, and it wasn't until the session was ended that I took it off."

|

"For

the painting which I did of him he sat in the large bow window of one

of his rooms. But my lithograph was made from a pencil sketch which I

drew one day when he was not feeling well and had received me while he

was still in his huge bed with its carved cherubim in the room on the

second floor." |

Then we went upstairs to his bedroom, in which, in contrast to the rest of the house, everything was in a delightful disorder. On the window-sill stood his shaving glass and cup, while on either side of a large dark wood Italian bed, with two carved angels over the head, were tables covered with books and pipes. Opening off of this room was his den, also filled with books, and how his eyes glistened as he showed the various little keepsakes which brought back the memories of dead years. A silver loving-cup, a Bismarck tobacco jar, a drawing by Howard Pyle of the menu for his seventieth birthday dinner, together with the gilded laurel wreath with which a young girl dressed as Joan of Arc had crowned him on that occasion. |

It was finally decided that the sofa in the room between the parlor and the dining-room would be the best place for him to pose. It was there as a usual thing he would sit after lunch and smoke and dream. On one side of the room was a large organ, and often during the sittings either his daughter or secretary would play. Music seems to appeal to him, rather from the associations it recalled than on its own account; and often when some old ballad or war song was played, a peculiar look would steal across his face, and his eyes would fill with tears; then, as the melody changed and some other remembrance came to him, he would pass it off with a light remark, joking in a way at his own seriousness. But that seemed to be especially characteristic of him--no matter how deep the thought that engaged his attention, by a peculiar process of mental conjuring he changed his appearance, or perhaps his point of view, so as to make it present a lighter side. In doing this he never for one moment lost sight of the original depth, but felt rather that by donning the cap an bells he could hold the attention and preach and amuse simultaneously.

At the end of one of the sitting he got up and came over to see the progress which I made on the picture.

"Make me beautiful," he said; "remember, truth is your most valuable possession; therefore don't waste it." At another time two friends, very tall men came in to see him, to ask him to take a walk on the avenue. "With you two!" said he, standing between them and taking each by the arm, "never, never shall it be said that Mark Twain was the cross-piece of a capital H."

His Interest in His Hair

After two or three sittings he saw that talking did not interfere with my work, and sometimes he conversed during the entire sitting. One day, however, he said: "I am afraid my talking bothers you. I guess you are one of the few people who would be willing to pay me to keep quiet." I assured him that such was by no means the case, and that, far from interfering with the progress of the picture, it helped me.

If he was vain about anything in his personal appearance, it was his hair; and that I should get it right in the picture seemed to give him the greatest concern. Several times he gave me suggestions as to the way he wore it, asking me to wait until he went upstairs and brushed it. Then he would come down with it rearranged, and I would get to work again.

As the head began to near completion, he wanted to know what I would do with his hands, for I had them only sketched in, so as to get the general arrangement of the entire figure on the canvas. "I guess a book would look better in them," he remarked, smilingly, one day, "even if a cigar is more natural." I solved the difficulty by putting a cigar in one hand and a book in the other, as one seemed as much a part of him as the other.

One day while I was there a prominent New York paper called him up on the telephone and offered to give one hundred dollars to any charity which he might name for a fifteen-minute interview on a certain subject which he did not care to discuss. The refusal worried him during the rest of the afternoon, and before I left he gave me a note to mail to a certain hospital, enclosing a check as contribution to its "conscience fund." In many other ways did he show the same spirit, and I can never forget how on one occasion when a severe snowstorm set in while I was at his house he insisted that I wear his overshoes home, assuring me that he was old enough to break any appointment on account of the weather, and that he would not need them again until it was clear, and then he did not wear them.

The last time he posed he was particularly reflective; in fact, he said very little during the entire sitting. While I was still there the expressman called for the picture to take it up to my studio. As it was being carried out, Mr. Clemens turned and said; "Now I feel as if I had attended my own funeral!"

The

old author was living in a large, old red brick building on the corner of 9th

Street and Fifth Avenue. For years I have had to combat secretaries whose chief

aim in life seems to be building a wall around their employers. Mark Twain's

secretary was the first one I encountered. She was fiercely efficient, haughty

to strangers and subservient to Mr. Clemens and his family. She gave the impression

that he could not be left alone, and all the time I worked she sat guarding

him and laughing at his remarks before he had finished making them. One of her

functions, apparently, was to show appreciation of his humor, which at that

time was not always in evidence.

He was old; his life had been a sad one and its sadness was reflected in the

humorist's manner. Occasionally his secretary sat at an automatic organ and

played while I worked, but I soon saw that his interest in music was primarily

a literary one, for the pieces which he asked for were sentimental ones--old

tunes of his youth.

He was much smaller in stature than his pictures led one to believe, and in his voice there was the suspicion of a Southern drawl. Even his head was disappointing, for while his shock of yellow-tinged white hair formed an impressive aura, his features in themselves were somewhat pinched.

He had recently completed his Life of Joan of Are and on the mantel was a laurel wreath of silver which a young woman, clad as France's heroine, had placed on his brow at a dinner given in his honor. It was symbolic of the fame he had achieved. Yet as he sat on a Colonial sofa near a bow window in that old Victorian house, he seemed more like a disappointed man than one whom the entire world acclaimed as great.

His thin, nervous hands constantly twisted a cigar, for he was an inveterate smoker and the edge of his mustache had a yellowish nicotine stain. When I suggested he hold a book in his hand he quizzically remarked, "I suppose the book looks better, but a cigar would be more like me."

He spoke slowly and almost weighed his words, and his conversation had little of the wit or sparkle I expected. His humor apparently was not spontaneous, but was the outcome of cold reason. Moreover, he bore a resentment against the affectations which he thought surrounded the culture of a large city. The artificiality of civilization palled upon him, and he had more respect for the man in the street than he had for book knowledge gathered in libraries.

He recalled that

when the play which he wrote with Warner was first produced, the same thing

happened as did when my uncle's play, The Mighty Dollar, opened. The critics

damned both of them, but he pointed out that there was a human quality in Colonel

Mulberry Sellers and Bardwell Slote, which the people recognized as true. They

went to see both shows in spite of what professional critics wrote.

"A critic," he drawled, "never made or killed a book or a play.

The people themselves are the final judges. It is their opinion that counts.

After all, the final test is truth. But the trouble is that most writers regard

truth as their most valuable possession and therefore are most economical in

its use."

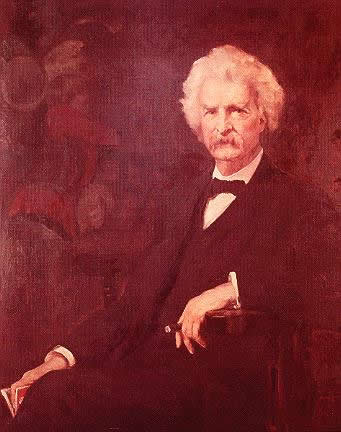

When I brought the portrait to my studio, the uncompromising north light made me dissatisfied with it. It was a large canvas, and in the background I had introduced the organ which was behind him as he posed. But this jarred the composition. I determined to change it--a very dangerous task, for painting, after all, is a matter of relations. An object takes on a certain tone because of the surrounding tones and if one part of a picture is changed it may throw the entire canvas out of harmony.

I was young and daring. Retaining the background immediately behind the head, I substituted a flat tone for the offending colored organ pipes. This did not satisfy me either; the canvas looked empty. Accordingly, I borrowed a piece of old tapestry. I introduced that, changing its design so as to improve the entire composition and suggesting Joan of Arc as one of the figures.

|

From an artistic standpoint the picture was a success. I first exhibited it at the Society of American Artists, where it received good notices, and Hy Mayer, who was then making a weekly page of caricatures for the New York Times, drew it with a crowd of laughing spectators about it, and labeled his drawing, "A Speaking Likeness." Neither the humorist nor his family liked it. That is the fate of most portraits. My picture of Mark Twain, despite the family's apathy, was bought by Thomas B. Clarke for the Brook Club's permanent collection of portraits of Americans by Americans. |

Cartoon by Hy Mayer The New York Times, January 13, 1907 |

Woolf's portrait of Mark Twain is now owned by the Mark Twain House in Hartford, CT. The Hartford Courant of November 23, 1947, reported the story of the acquisition which was brought about by the efforts of Mrs. Stiles Burpee who discovered a colored lithograph of the original portrait in her attic and launched an effort to find the original portrait. Through chance circumstances, Hartford art gallery owner and art restorer Karl Gregor received word that a number of the Thomas B. Clarke portraits were being sold and he determined to acquire the portrait in order to bring it to Hartford.

|

Extensive fundraising efforts by Mrs. Stiles Burpee enabled the acquisition of the portrait for the Mark Twain House in Hartford. The restoration of the portrait that was conducted by Gregor included the cropping of the portrait so that very little detail remains of the Joan of Arc tapestry that Woolf created. The portrait was later loaned to the National Portrait Gallery. In 1983, it was once again returned to Hartford. A minor accident to the lower portion of the portrait necessitate further repair and cleaning. |

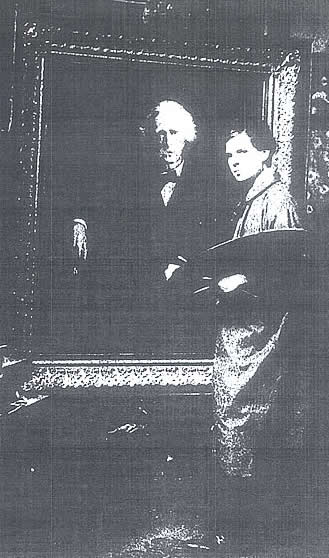

Mrs. Stiles Burpee and Karl Gregor. Hartford Courant Magazine, Nov. 23, 1947. |

| Throughout the last century, the cropping and restoration processes of the portrait have left Twain's features bright but have darkened and destroyed the Joan of Arc tapestry background of Woolf's original artwork. Without the visual cues of Joan of Arc and her horse which have been cropped away, the viewer is left to wonder and speculate what Woolf had been attempting to paint in the portrait's background. The best record of what the original painting once looked like is now found in the 1906 lithographs. Two of the lithographs are known to exist. Mrs. Burpee donated her lithograph to the Mark Twain House in Hartford. Another is held in the collection of rare book dealer Kevin Mac Donnell in Austin, TX. |

The Woolf portrait as it appears today. Photo courtesy of Dave Thomson. |

|

The June 17, 1906 edition of The New York Times featured a photograph of Samuel Johnson Woolf alongside a portrait. The photo was titled PAINTING

MARK TWAIN'S PORTRAIT The portrait does not resemble the known portrait that Woolf painted of Mark Twain. Did Woolf destroy this portrait and start anew? Did The New York Times misidentify the portrait? If anyone can identify the gentleman in the portrait, please email me. |

Quotations | Newspaper Articles | Special Features | Links | Search