Quotations | Newspaper Articles | Special Features | Links | Search

SPECIAL FEATURE

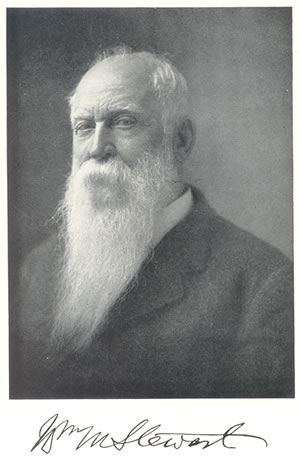

REMINISCENCES OF SENATOR WILLIAM M. STEWART OF NEVADA.

Edited by George Rothwell Brown.

The Neale Publishing Company, 1908.

Pages 219-224.

Quotations | Newspaper Articles | Special Features | Links | Search

REMINISCENCES OF SENATOR WILLIAM M. STEWART OF NEVADA.

Edited by George Rothwell Brown.

The Neale Publishing Company, 1908.

Pages 219-224.

CHAPTER XXIII

Mark Twain becomes my secretary--Back from the Holy Land, and he looks it--The landlady terrorized--I interfere with a humorist's pleasures, and get a black patch--Revenge! Clemens the hero of a Nevada hold-up.

About the winter of 1867, I think, while my family was in Paris, I lived in

a rather tumble-down building which at that time stood on the northwest corner

of Fourteenth and F Streets, N. W., opposite the old Ebbitt House, where many

of my Congressional cronies had quarters. The house was a weather-beaten old

place, a relic of early Washington.

Its proprietress was Miss Virginia Wells, an estimable lady about 70 years of age, prim, straight as a ramrod, and with smooth-plastered white hair. She belonged to one of the first families of Virginia, which were quite numerous in Washington, and was very aristocratic; but having lost everything in the war, she had come to Washington, and managed to make a precarious living as a lodging-house keeper.

I had the second floor of her residence, one of the rooms, facing upon both streets, a spacious apartment about seventy-five feet long, which I had divided by a curtain drawn across it, making a little chamber at the rear, in which I slept. The front part was my sitting-room. I had a desk there, and tables, with writing materials, and my books, and a sideboard upon which I kept at all times plenty of cigars and a supply of whiskey, for I occasionally smoked and took a drink of liquor.

I was seated at my window one morning when a very disreputable-looking person slouched into the room. He was arrayed in a seedy suit, which hung upon his lean frame in bunches with no style worth mentioning. A sheaf of scraggy black hair leaked out of a battered old slouch hat, like stuffing from an ancient Colonial sofa, and an evil-smelling cigar butt, very much frazzled, protruded from the corner of his mouth. He had a very sinister appearance. He was a man I had known around the Nevada mining camps several years before, and his name was Samuel L. Clemens.

I suppose he was the most lovable scamp and nuisance who ever blighted Nevada. When I first knew him he was a reporter on the Territorial Enterprise which was otherwise a very reputable paper published in Virginia City, and his brother, Orion Clemens, was a respectable young gentleman, and well liked.

Sam Clemens was a busy person. He went around putting things in the paper about people, and stirring up trouble. He did not care whether the things he wrote were true or not, just so he could write some thing, and naturally he was not popular. I did not associate with him.

This Clemens one day wrote something about a distinguished citizen of Virginia City, a friend of mine, which was entirely characteristic of Clemens, as it had not the slightest foundation in fact. I remonstrated with him.

"You are getting worse every day," I said. "Why can't you be genial, like your brother Orion? You ought to be hung for what you have published this morning.

"I don't mean anything by that," returned Clemens. "I do not know this friend of yours. For all I am aware he may be a very desirable and conscientious man. But I must make a living, and so I must write. My employers demand it, and I am helpless."

He said he wrote it "because it was humorous." Maybe it was. I did not undertake to argue with him. I could not see it, and so I let it go at that.

Clemens had a great habit of making fun of the young fellows and the girls, and wrote ridiculous pieces about parties and other social events, to which he was never invited. After a while he went over to Carson City, and touched up the people over there, and got everybody down on him. I thought he had faded from our midst forever, but the citizens of Carson drove him away. At any rate, he drifted back to Virginia City in a few weeks. He didn't have a friend, but the boys got together and said they would give a party, and invite Clemens to it, and make him feel at home, and respectable and decent, and kindly, and generous, and loving, and considerate of the feelings of others. I could have warned them, but I didn't.

Clemens went to that party and danced with the prettiest girls, and monopolized them, and enjoyed himself, and made a good meal, and then shoved over to the Enterprise office and wrote the whole thing up in an outrageous manner. He lambasted that party for all the English language would allow, and if any of the guests was unfortunate enough to be awkward or had big feet, or a wart on the nose, Clemens did not forget it. He fairly strained his memory.

Of course this made the boys angry, and we decided to get even. There was a stage that ran from Carson to Virginia City, and Clemens was a passenger on it one night The boys laid in wait, and when the stage lumbered by a lonely spot they swooped out, and upset it, and turned it upside down, and dragged Clemens out and threw him in a canyon, and broke up his portmanteau, and threw that in on top of him. He was the scaredest man west of the Mississippi; but the next morning, when he crawled back to town, and it was day, and light, and safe, he began to swell a little, and pretty soon he was bragging about his narrow escape. By and by he began to color it up, and add details that he had overlooked at first, until he made out that he had been in one of the most desperate stage robberies in the history of the West, and it was a pretty poor story that he couldn't lug that one into, by the nape of the neck, sort of casually.

After that he drifted away, and I thought he had been hanged, or elected to Congress, or something like that, and I had forgotten him, until he slouched into my room, and then of course I remembered him. I said:

"If you put anything in the paper about me I'll sue you for libel." He waved the suggestion aside with easy familiarity.

"Senator," he said, "I've come to see you on important business. I am just back from the Holy Land."

"That is a mean thing to say of the Holy Land when it isn't here to defend itself," I replied, looking him over. "But maybe you didn't get all the advantages. You ought to go back and take a post graduate course. Did you walk home?"

"I have a proposition," said Clemens, not at all ruffled. "There's millions in it. All I need is a little cash stake. I have been to the Holy Land with a party of innocent and estimable people who are fairly aching to be written up, and I think I could do the job neatly and with dispatch if I were not troubled with other--more--pressing-considerations. I've started the book already, and it is a wonder. I can vouch for it."

"Let me see the manuscript," I said. He pulled a dozen sheets or so from his pocket and handed them to me. I read what he had written, and saw that it was bully, so I continued, "I'll appoint you my clerk at the Senate, and you can live on the salary. There's a little hall bedroom across the way where you can sleep, and you can write your book in here. Help your self to the whiskey and cigars, and wade in."

He accepted all of my invitations, in the modest and unassuming manner for which he had been noted in Nevada, and became a member of my family, and my clerk.

It was not long before Clemens took notice of Miss Virginia. Her timid, aristocratic nature shrank from him, and I think she was half afraid of him. He did not overlook any opportunities to make her life miserable, and was always playing some joke on her. He would lurch around the halls, pretending to be intoxicated, and would throw her into a fit about six times a day.

He would burn the light in his bedroom all night, and started her figuring up her expense account with a troubled, anxious face. Pretty soon he took to smoking cigars in bed.

She never slept after this discovery, but every night would lie awake, with her clothes handy on a chair, expecting the house to be burned down any minute, and ready to skip out at the first alarm; and she became so pale, and thin, and wasted, and troubled that it would have melted a pirate's heart to see her. She crept to my room one day, the mere shadow of her former self. She no longer leaned over backward, as she usually did, because of being so straight and dignified, but was badly bent. I was shocked.

"Senator," she said, "if you don't ask that friend of yours to leave I shall have to give up my lodging house, and God knows what will become of me then. He smokes cigars in bed all night, and has ruined my best sheets, and I expect to be burned out any time. I've been on the alert now for three weeks, but I can't keep it up much longer. I need sleep."

I told her to leave the room, and I called Clemens. He slouched in.

"Clemens," I said, "if you don't stop annoying this little lady I'll give you a sound thrashing--I'll wait till that book's finished. I don't want to interfere with literature--I'll thrash you after it's finished."

He blew some smoke in my face.

"You are mighty unreasonable," he replied. "Why do you want to interfere with my pleasures?"

I thought he would behave himself after that. But one day a week later Miss Virginia staggered into my room again, in a flood of tears. She said:

"Senator, that man will kill me. I can't stand it. If he doesn't go I'll have to ask you to give up your rooms, and the Lord knows whether I'll be able to rent them again."

This filled me with alarm. I was very comfortable where I was. I sent her away kindly, and called Clemens. He slouched in again.

"You have got to stop this foolishness," I said. "If you don't cease annoying this little lady I'll amend my former resolution, and give you that thrashing here and now. Then I'll send you to the hospital, and pay your expenses, and bring you back, and you can finish your book upholstered in bandages." He saw that I meant business.

"All right," he replied, "I'll give up my amusements, but I'll get even with you."

He did. When he wrote "Roughing It" he said I had cheated him out of some mining stock or something like that, and that he had given me a sound thrashing; and he printed a picture of me in the book, with a patch over one eye.

Clemens remained with me for some time. He wrote his book in my room, and named it "The Innocents Abroad." I was confident that he would come to no good end, but I have heard of him from time to time since then, and I understand that he has settled down and become respectable.

Quotations | Newspaper Articles | Special Features | Links

| Search