DEATH

|

|

|

Introduction Mark Twain's "Death Disk" was inspired by the historical account of the execution of Colonel John Poyer of Pembroke, Wales on April 21, 1649. A small child was given the responsibility of selecting which of three rebel leaders of a civil uprising would receive a death penalty. The unfortunate fate was given to Poyer who was shot in front of a large crowd at Covent Garden. In 1883 Twain read about the child's role in the execution in a copy of Carlyle's Letters and Speeches of Oliver Cromwell, (Wiley & Putnam, 1845, pp. 344-345). In his personal notebook, Twain's imagination led him to remark, "By dramatic accident it could have been his own child" (Notebook #22, reprinted in Mark Twain's Notebooks & Journals, Volume III, 1883-1891, p. 14). In December 1883, Twain wrote his friend William Dean Howells, "Now let's write a tragedy" (Mark Twain-Howells Letters, Volume II, p. 455). In his letter to Howells, he included the manuscript of the closing scene where a young girl unknowingly gives her own father a death sentence. Twain's original version ended in the father's execution. Twain's plan to complete the tragedy went nowhere for over a decade. In December 1899 he wrote from London to Katharine Harrison that he had recently completed "The Death Disk." Twain had revised the story and it now included a miraculous ending well-suited for the Christmas season. It was published in the 1901 Christmas issue of Harper's Magazine. On February 8, 1902, the story was staged as a one-act play at the Children's Theatre at Carnegie Hall. According to an announcement in The New York Times, February 7, 1902, child actress Beatrice Abbey (stage name of Mrs. Ethel Foster Hollearn) would star in the lead role in the play titled "Little Lady and Lord Cromwell." In Twain's autobiographical dictation on August 30, 1906, he recalled the struggles he had with the story. By that time he also recalled the title incorrectly:

In 1909 Biograph released "The Death Disk" as a silent film directed by D.W. Griffith. |

_____

The text for this story is a touching incident mentioned in Carlyle's Letters and Speeches of Oliver Cromwell. - M. T.

This was in Oliver Cromwell's time. Colonel Mayfair was the youngest officer of his rank in the armies of the Commonwealth, he being but thirty years old. But young as he was, he was a veteran soldier, and tanned and war-worn, for he had begun his military life at seventeen; he had fought in may battles, and had won his high place in the service and in the admiration of men, step by step, by valor in the field. But he was in deep trouble now; a shadow had fallen upon his fortunes.

The winter evening was come, and outside were storm and darkness; within, a melancholy silence; for the Colonel and his young wife had talked their sorrow out, had read the evening chapter and prayed the evening prayer, and there was nothing more to do but sit hand in hand and gaze into the fire, and think - and wait. They would not have to wait long; they knew that, and the wife shuddered at the thought.

They had one child - Abby, seven years old, their idol. She would be coming presently for the good-night kiss, and the Colonel spoke now, and said:

"Dry away the tears and let us seem happy, for her sake. We must forget, for the time, that which is to happen."

"I will. I will shut them up in my heart, which is breaking."

"And we will accept what is appointed for us, and bear it in patience, as knowing that whatsoever He doeth is done in righteousness and meant in kindness - "

"Saying, His will be done. Yes, I can say it with all my mind and soul - I would I could say it with my heart. Oh, if I could! if this dear hand which I press and kiss for the last time - "

"Sh! sweetheart, she is coming!"

A curly-headed little figure in night-clothes glided in at the door and ran to the father, and was gathered to his breast and fervently kissed once, twice, three times. "Why, papa, you mustn't kiss me like that; you rumple my hair."

"Oh, I am so sorry - so sorry: do you forgive me, dear?"

"Why, of course, papa. But are you sorry? - not pretending, but real, right down sorry?"

"Well, you can judge for yourself, Abby," and he covered his face with his hands and made believe to sob. The child was filled with remorse to see this tragic thing which she had caused, and she began to cry herself, and to tug at the hands, and say:

"Oh, don't, papa, please don't cry; Abby didn't mean it; Abby wouldn't ever do it again. Please, papa!" Tugging and straining to separate the fingers, she got a fleeting glimpse of an eye behind them, and cried out: "Why, you naughty papa, you are not crying at all! You are only fooling! And Abby is going to mamma, now: you don't treat Abby right."

She was for climbing down, but her father wound his arms about her and said: "No, stay with me, dear: papa was naughty, and confesses it, and is sorry - there, let him kiss the tears away - and he begs Abby's forgiveness, and will do anything Abby says he must do, for a punishment; they're all kissed away now, and not a curl rumpled - and whatever Abby commands - "

And so it was made up; and all in a moment the sunshine was back again and burning brightly in the child's face, and she was patting her father's cheeks and naming the penalty - "A story! a story!"

Hark!

The elders stopped breathing and listened. Footsteps! faintly caught between the gusts of wind. They came nearer, nearer - louder, louder - then passed by and faded away. The elders drew deep breaths of relief, and the papa said: "A story, is it? A gay one?"

"No, papa: a dreadful one." Papa wanted to shift to the gay kind, but the child stood by her rights - as per agreement, she was to have anything she commanded. He was a good Puritan soldier and had passed his word - he saw that he must make it good. She said: "Papa, we mustn't always have gay ones. Nurse says people don't always have gay times. Is that true, papa? She says so."

The mamma sighed, and her thoughts drifted to her troubles again. The papa said, gently: "It is true, dear. Troubles have to come; it is a pity, but it is true."

"Oh, then tell a story about them, papa - a dreadful one, so that we'll shiver, and feel just as if it was us. Mamma, you snuggle up close, and hold one of Abby's hands, so that if it's too dreadful it'll be easier for us to bear it if we are all snuggled up together, you know. Now you can begin, papa."

"Well, once there were three Colonels - "

"Oh, goody! I know Colonels, just as easy! It's because you are one, and I know the clothes. Go on, papa."

"And in a battle they had committed a breach of discipline."

The large words struck the child's ear pleasantly, and she looked up, full of wonder and interest, and said:

"Is it something good to eat, papa?"

The parents almost smiled, and the father answered:

"No, quite another matter, dear. They exceeded their orders."

"Is that someth - "

"No; it's as uneatable as the other. They were ordered to feign an attack on a strong position in a losing fight, in order to draw the enemy about and give the Commonwealth's forces a chance to retreat; but in their enthusiasm they overstepped their orders, for they turned their feint into a fact, and carried the position by storm, and won the day and the battle. The Lord General was very angry at their disobedience, and praised them highly, and ordered them to London to be tried for their lives."

"Is it the great General Cromwell, papa?"

"Yes."

"Oh, I've seen him, papa! and when he goes by our house so grand on his big horse, with the soldiers, he looks so - so - well, I don't know just how, only he looks as if he isn't satisfied, and you can see the people are afraid of him; but I'm not afraid of him, because he didn't look like that at me."

"Oh, you dear prattler! Well, the Colonels came prisoners to London, and were put upon their honor, and allowed to go and see their families for the last - "

Hark!

They listened. Footsteps again; but again they passed by. The mamma leaned her head upon her husband's shoulder to hide her paleness.

"They arrived this morning."

The child's eyes opened wide.

"Why, papa! is it a true story?"

"Yes, dear."

"Oh, how good! Oh, it's ever so much better! Go on, papa. Why, mamma! - dear mamma, are you crying?"

"Never mind, dear - I was thinking of the - of the - poor families."

"But don't cry, mamma: it'll all come out right - you'll see; stories always do. Go on, papa, to where they lived happy ever after; then she won't cry any more. You'll see, mamma. Go on, papa."

"First, they took them to the Tower before they let them go home."

"Oh, I know the Tower! We can see it from here. Go on, papa."

"I am going on as well as I can, in the circumstances. In the Tower the military court tried them for an hour, and found them guilty, and condemned them to be shot."

"Killed, papa?"

"Yes."

"Oh, how naughty! Dear mamma, you are crying again. Don't, mamma; it'll soon come to good place - you'll see. Hurry, papa, for mamma's sake; you don't go fast enough."

"I know I don't, but I suppose it is because I stop so much to reflect."

"But you mustn't do it, papa; you must go right on."

"Very well, then. The three Colonels - "

"Do you know them, papa?"

"Yes, dear."

"Oh, I wish I did! I love Colonels. Would they let me kiss them, do you think?" The Colonel's voice was a little unsteady when he answered -

"One of them would, my darling! There - kiss me for him."

"There, papa - and these two are for the others. I think they would let me kiss them, papa; for I would say, 'My papa is a Colonel, too, and brave, and he would do what you did; so it can't be wrong, no matter what those people say, and you needn't be the least bit ashamed'; then they would let me - wouldn't they, papa?"

"God knows they would, child!"

"Mamma! - oh, mamma, you mustn't. He's soon coming to the happy place; go on, papa."

"Then, some were sorry - they all were; that military court, I mean; and they went to the Lord General, and said they had done their duty - for it was their duty, you know - and now they begged that two of the Colonels might be spared, and only the other one shot. One would be sufficient for an example for the army, they thought. But the Lord General was very stern, and rebuked them forasmuch as, having done their duty and cleared their consciences, they would beguile him to do less, and so smirch his soldierly honor. But they answered that they were asking nothing of him that they would not do themselves if they stood in his great place and held in their hands the noble prerogative of mercy. That stuck him, and he paused and stood thinking, some of the sternness passing out of his face. Presently he bid them wait, and he retired to his closet to seek counsel of God in prayer; and when he came again, he said: 'They shall cast lots. That shall decide it, and two of them shall live.'"

"And did they, papa, did they? And which one is to die? - ah, that poor man!"

"No. They refused."

"They wouldn't do it, papa?"

"No."

"Why?"

"They said that the one that got the fatal bean would be sentencing himself to death by his own voluntary act, and it would be but suicide, call it by what name one might. They said they were Christians, and the Bible forbade men to take their own lives. They sent back that word, and said they were ready - let the court's sentence be carried into effect."

"What does that mean, papa?"

"They - they will all be shot."

Hark!

The wind? No. Tramp - tramp - r-r-r-umble-dumdum, r-r-rumble-dumdum -

"Open - in the Lord General's name!"

"Oh, goody, papa, it's the soldier's! - I love the soldiers! Let me let them in, papa, let me!"

She jumped down, and scampered to the door and pulled it open, crying joyously: "Come in! come in! Here they are, papa! Grenadiers! I know the Grenadiers!"

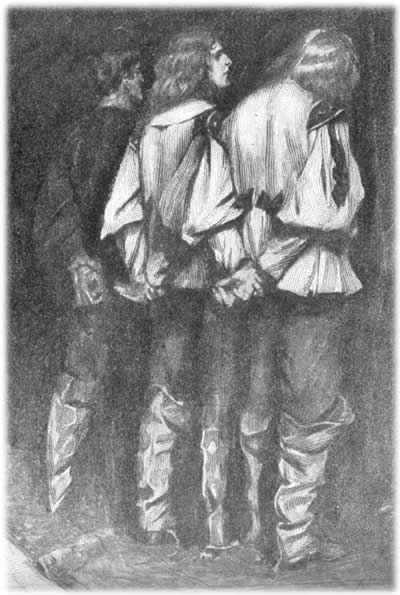

The file marched in and straightened up in line at shoulder arms; its officer saluted, the doomed Colonel standing erect and returning the courtesy, the soldier wife standing at his side, white and with features drawn with inward pain, but giving no other sign of her misery, the child gazing on the show with dancing eyes. . . .

One long embrace, of father, mother, and child; then the order, "To the Tower - forward!" Then the Colonel marched forth from the house with military step and bearing, the file following; then the door closed.

"Oh, mamma, didn't it come out beautiful! I told you it would; and they're going to the Tower, and he'll see them! He - "

"Oh, come to my arms, you poor innocent thing!" . . .

The next morning the stricken mother was not able to leave her bed; doctors and nurses were watching by her, and whispering together now and then. Abby could not be allowed in the room, she was told to run and play - mamma was very ill. The child, muffled in winter wraps, went out and played in the street awhile; then it struck her as strange, and also wrong, that her papa should be allowed to stay at the Tower in ignorance at such a time as this. This must be remedied; she would attend to it in person.

An hour later the military court were ordered into the presence of the Lord General. He stood grim and erect, with his knuckles resting upon the table, and indicated that he was ready to listen. The spokesman said: "We have urged them to reconsider; we have implored them; but they persist. They will not cast lots. They are willing to die, but not to defile their religion."

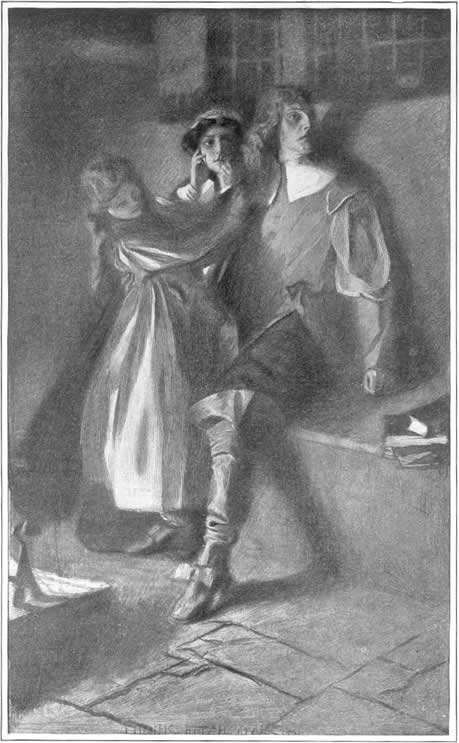

The Protector's face darkened, but he said nothing. He remained a time in thought, then he said: "They shall not all die; the lots shall be cast for them." Gratitude shone in the faces of the court. "Send for them. Place them in that room there. Stand them side by side with their faces to the wall and their wrists crossed behind them. Let me have notice when they are there."

When he was alone he sat down, and promptly gave this order to an attendant: "Go, bring me the first little child that passes by."

The man was hardly out at the door before he was back again - leading Abby by the hand, her garments lightly powdered with snow. She went straight to the Head of the State, that formidable personage at the mention of whose name the principalities and powers of the earth trembled, and climbed up in his lap and said:

"I know you, sir; you are the Lord General; I have seen you; I have seen you when you went by my house. Everybody was afraid; but I wasn't afraid, because you didn't look cross at me; you remember, don't you? I had on my red frock - the one with the blue things on it down the front. Don't you remember that?"

A smile softened the austere lines of the Protector's face, and he began to struggle diplomatically with his answer:

"Why, let me see - I -"

"I was standing right by the house - my house, you know."

"Well, you dear little thing, I ought to be ashamed, but you know - "

The child interrupted, reproachfully:

"Now, you don't remember it. Why, I didn't forget you."

"Now I am ashamed, but I will never forget you again, dear; you have my word for it. You will forgive me now, won't you, and be good friends with me, always and forever?"

"Yes, indeed I will, though I don't know how you came to forget it; you must be forgetful; but I am too, sometimes. I can forgive you without any trouble, for I think you mean to be good and do right, and I think you are just as kind - but you must snuggle me better, the way papa does - it's cold."

| "You shall be snuggled to your heart's content, little new friend of mine, always to be old friend of mine hereafter, isn't it? You mind me of my little girl - not little any more, now - but she was dear, and sweet, and daintily made, like you. And she had your charm, little witch - your all-conquering sweet confidence in friend and stranger alike, that wins to willing slavery any upon whom its precious compliment falls. She used to lie in my arms, just as you are doing now; and charm the weariness and care out of my heart and give it peace, just as you are doing now; and we were comrades, and equals, and playfellows together. Ages ago it was, since that pleasant heaven faded away and vanished, and you have brought it back again; - take a burdened man's blessing for it, you tiny creature, who are carrying the weight of England while I rest!" |  |

"Did you love her very, very, very much?"

"Ah, you shall judge by this; she commanded and I obeyed!"

"I think you are lovely! Will you kiss me?"

"Thankfully - and hold it a privilege, too. There - this one is for you; and there - this one is for her. You made it a request; and you could have made it a command, for you are representing her, and what you command I must obey."

The child clapped her hands with delight at the idea of this grand promotion - then her ear caught an approaching sound; the measured tramp of marching men."Soldiers! - soldiers, Lord General! Abby wants to see them!"

"You shall, dear; but wait a moment, I have a commission for you."

An officer entered and bowed low, saying "They are come, your Highness." bowed again, and retired.

The Head of the Nation gave Abby three little disks of sealing-wax; two white, and one of ruddy red - for this one's mission was to deliver death to the Colonel who should get it. "Oh, what a lovely red one! Are they for me?"

"No, dear; they are for others. Lift the corner of that curtain, there, which hides an open door; pass through, and you will see three men standing in a row, with their backs toward you and their hands behind their backs - so - each with one hand open, like a cup. Into each of the open hands drop one of those things, then come back to me."

Abby disappeared behind the curtain, and the Protector was alone. He said, reverently: "Of a surety that good thought came to me in my perplexity from Him who is an ever-present help to them that are in doubt and seek His aid. He knoweth where the choice should fall, and has sent His sinless messenger to do His will. Another would err, but He cannot err. Wonderful are His ways, and wise - blessed be His holy Name!"

The small fairy dropped the curtain behind her and stood for a moment examining with alert curiosity the appointments of the chamber of doom, and the rigid figures of the soldiery and the prisoners; then her face lighted merrily, and she said to herself: "Why, one of them is papa! I know his back. He shall have the prettiest one!" She tripped gaily forward and dropped the disks into the open hands, then peeped around under her father's arm and lifted her laughing face and cried out:

"Papa! look what you've got. I gave it to you!"

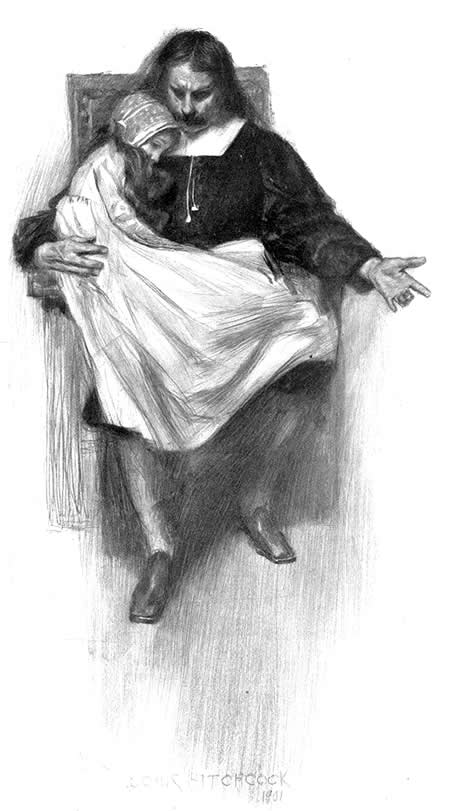

He glanced at the fatal gift, then sunk to his knees and gathered his innocent little executioner to his breast in an agony of love and pity. Soldiers, officers, released prisoners, all stood paralyzed, for a moment, at the vastness of this tragedy, then the pitiful scene smote their hearts, their eyes filled, and they wept unashamed. There was deep and reverent silence during some minutes, then the officer of the guard moved reluctantly forward and touched his prisoner on the shoulder, saying, gently:

"It grieves me, sir, but my duty commands."

"Commands what?" said the child.

"I must take him away. I am so sorry."

"Take him away? Where?"

"To - to - God help me! - to another part of the fortress."

"Indeed you can't. My mamma is sick, and I am going to take him home." She released herself and climbed upon her father's back and put her arms around his neck. "Now Abby's ready, papa - come along."

"My poor child, I can't. I must go with them."

The child jumped to the ground and looked about her, wondering. Then she ran and stood before the officer and stamped her small foot indignantly and cried out:

"I told you my mamma is sick, and you might have listened. Let him go - you must!"

"Oh, poor child, would God I could, but indeed I must take him away. Attention, guard! . . . fall in! . . . shoulder arms!" . . .

Abby was gone - like a flash of light.

In a moment she was back, dragging the Lord Protector by the hand. At this formidable apparition all present straightened up, the officers saluting and the soldiers presenting arms.

"Stop them, sir! My mamma is sick and wants my papa, and I told them so, but they never listened to me and are taking him away."

The Lord General stood as one dazed.

"Your papa, child? Is he your papa?"

"Why, of course - he was always it. Would I give the pretty red one to any other, when I love him so? No!"

A shocked expression rose in the Protector's face, and he said:

"Ah, God help me! through Satan's wiles I have done the cruelest thing that ever man did - and there is no help, no help! What can I do?"

Abby cried out, distressed and impatient: "Why you can make them let him go," and she began to sob. "Tell them to do it! You told me to command, and now the very first time I tell you to do a thing you don't do it!"

A tender light dawned in the rugged old face, and the Lord General laid his

hand upon the small tyrant's head and said: "God be thanked for the saving

accident of that unthinking promise; and you inspired by Him, for reminding

me of my forgotten pledge, O incomparable child! Officer, obey her command -

she speaks by my mouth. The prisoner is pardoned; set him free!"