"WE WILL CONFISCATE

HIS NAME"

|

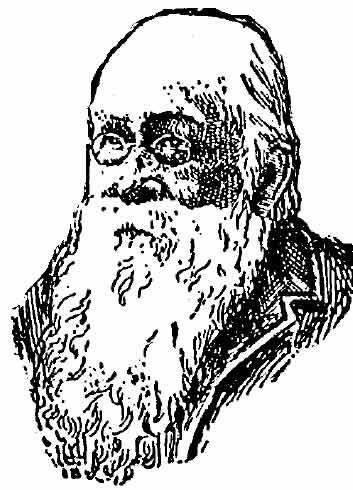

George Escol Sellers (1808-1899) from The Atlanta Constitution, September 8, 1901, p. A1 |

THE GILDED AGE

The Gilded Age started out as a challenge by two wives sitting around a Hartford, Connecticut dining table in the spring of 1873. Olivia Clemens and Susan Warner challenged their husbands to write a "better" American novel. Samuel Clemens, "Mark Twain," already had two successful books in print published by the Hartford based American Publishing Company. Charles Dudley Warner, editor of the local Hartford Courant newspaper, was willing to undertake the wives' challenge. The book, a joint collaboration, would be the first fiction novel for both men. Writing different sections of the book, the two authors completed the challenge and their joint work titled The Gilded Age was issued in December 1873. The book received favorable reviews and was later adapted into a long running successful stage production starring actor John T. Raymond.

One of the best descriptions of the novel is by R. Kent Rasmussen in Mark Twain Z to A:

The novel skewers government and politicians, big business and America's obsession with getting rich. It is now best remembered for its title, which gave its name to the era that it describes.

While The Gilded Age touches on many themes as it shifts uncomfortably between melodrama and satire, occasionally verging into burlesque, it always projects a powerful message about the futility and self-destructiveness of chasing after riches. This theme is personified in the character of Colonel Sellers, who sees "millions" in countless visionary schemes, though he rarely rises above grinding poverty (Rasmussen, pp. 166-167).

Twain, who created the character, claimed Colonel Sellers was based on his mother's favorite cousin, James Lampton. Twain's mother Jane Lampton Clemens was the daughter of Benjamin Lampton. Benjamin Lampton's brother was Lewis Lampton who was the father of James Lampton. In Mark Twain's Autobiography, Twain described him:

James Lampton floated, all his days, in a tinted mist of magnificent dreams, and died at last without seeing one of them realized. I saw him last in 1884, when it had been twenty-six years since I ate the basin of raw turnips and washed them down with a bucket of water in his house. He was become old and white-headed, but he entered to me in the same old breezy way of his earlier life, and he was all there, yet -- not a detail wanting: the happy light in his eye, the abounding hope in his heart, the persuasive tongue, the miracle-breeding imagination -- they were all there; and before I could turn around he was polishing up his Aladdin`s lamp and flashing the secret riches of the world before me. I said to myself, "I did not overdraw him by a shade, I set him down as he was; and he is the same man to-day..." (Mark Twain's Autobiography, Vol. 1, p. 91-92).

Twain also further elaborated on his character of Colonel Sellers on stage:

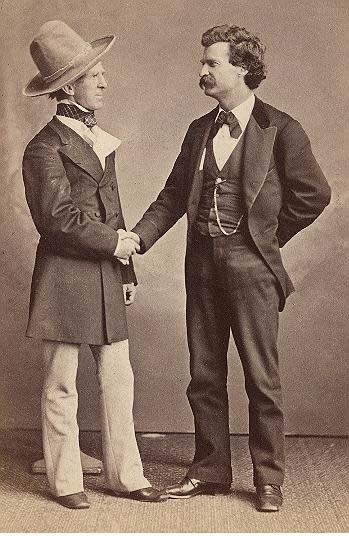

| Many persons regarded "Colonel Sellers" as a fiction, an invention, an extravagant impossibility, and did me the honor to call him a "creation"; but they were mistaken. I merely put him on paper as he was; he was not a person who could be exaggerated. The incidents which looked most extravagant, both in the book and on the stage, were not inventions of mine but were facts of his life; and I was present when they were developed. John T. Raymond's audiences used to come near to dying with laughter over the turnip-eating scene; but, extravagant as the scene was, it was faithful to the facts, in all its absurd details. The thing happened in Lampton`s own house, and I was present. In fact I was myself the guest who ate the turnips. In the hands of a great actor that piteous scene would have dimmed any manly spectator`s eyes with tears, and racked his ribs apart with laughter at the same time. But Raymond was great in humorous portrayal only. In that he was superb, he was wonderful -- in a word, great; in all things else he was a pigmy of the pigmies. The real Colonel Sellers, as I knew him in James Lampton, was a pathetic and beautiful spirit, a manly man, a straight and honorable man, a man with a big, foolish, unselfish heart in his bosom, a man born to be loved; and he was loved by all his friends, and by his family worshipped. It is the right word. To them he was but little less than a god. The real Colonel Sellers was never on the stage. Only half of him was there. Raymond could not play the other half of him; it was above his level. That half was made up of qualities of which Raymond was wholly destitute. For Raymond was not a manly man, he was not an honorable man nor an honest one, he was empty and selfish and vulgar and ignorant and silly, and there was a vacancy in him where his heart should have been. There was only one man who could have played the whole of Colonel Sellers, and that was Frank Mayo (Mark Twain's Autobiography, Vol. 1, pp. 89-90). |  Mark Twain and actor John Raymond who played the title role in "Colonel Sellers" which was based on the novel The Gilded Age. From the Dave Thomson collection. |

The success of the novel and the stage play grew and spread across the country. However, an eagle-eyed observer may have noticed something unusual that took place during those first years of the book's publication. A subtle change was made in the name of the character of Colonel Sellers. Copies of first editions of The Gilded Age contained the name of Colonel Eschol Sellers. Later editions contained the name Colonel Beriah Sellers. And the name Beriah mutated into Colonel Mulberry Sellers in the stage productions. Mark Twain first offered an explanation of the name change to his readers some years later in his book Life on the Mississippi:

It came out in conversation, that in two different instances Mr. [George Washington] Cable got into grotesque trouble by using, in his books, next-to-impossible French names which nevertheless happened to be borne by living and sensitive citizens of New Orleans. His names were either inventions or were borrowed from the ancient and obsolete past, I do not now remember which; but at any rate living bearers of them turned up, and were a good deal hurt at having attention directed to themselves and their affairs in so excessively public a manner.

Mr. Warner and I had an experience of the same sort when we wrote the book called 'The Gilded Age.' There is a character in it called 'Sellers.' I do not remember what his first name was, in the beginning; but anyway, Mr. Warner did not like it, and wanted it improved. He asked me if I was able to imagine a person named 'Eschol Sellers.' Of course I said I could not, without stimulants. He said that away out West, once, he had met, and contemplated, and actually shaken hands with a man bearing that impossible name--'Eschol Sellers.' He added -

'It was twenty years ago; his name has probably carried him off before this; and if it hasn't, he will never see the book anyhow. We will confiscate his name. The name you are using is common, and therefore dangerous; there are probably a thousand Sellerses bearing it, and the whole horde will come after us; but Eschol Sellers is a safe name -- it is a rock.'

So we borrowed that name; and when the book had been out about a week, one of the stateliest and handsomest and most aristocratic looking white men that ever lived, called around, with the most formidable libel suit in his pocket that ever--well, in brief, we got his permission to suppress an edition of ten million (Figures taken from memory, and probably incorrect. Think it was more.) copies of the book and change that name to 'Mulberry Sellers' in future editions.

- Life on the Mississippi, chapter 47

When Twain again used the character of Colonel Sellers in his 1892 novel The American Claimant, he offered this explanation in a preface::

The Colonel Mulberry Sellers here reintroduced to the public is the same person who appeared as Eschol Sellers in the first edition of the tale entitled The Gilded Age, years ago, and as Beriah Sellers in the subsequent editions of the same book, and finally as Mulberry Sellers in the drama played afterward by John T. Raymond.

The named was changed from Eschol to Beriah to accommodate an Eschol Sellers who rose up out of the vasty deeps of uncharted space and preferred his request -- backed by a threat of a libel suit -- then went on his way appeased, and came no more. In the play Beriah had to be dropped to satisfy another member of the race, and Mulberry was substituted in hope that the objectors would be tired by that time and let it pass unchallenged. So far it has occupied the field in peace; therefore we chance it once again, feeling reasonably safe, this time, under the shelter of the statute of limitations.

MARK TWAIN

Hartford, 1891

There is no evidence to date of any objections from a man by the name of Beriah Sellers and this explanation may have been an exaggeration by Twain for dramatic effect.

As the years progressed, Twain continued to blame Warner for the Sellers name fiasco. In his Autobiography, he gave another version of the name affair:

It is a world of surprises. They fall, too, where one is least expecting them. When I introduced Sellers into the book, Charles Dudley Warner, who was writing the story with me, proposed a change of Sellers's Christian name. Ten years before, in a remote corner of the West, he had come across a man named Eschol Sellers, and he thought that Eschol was just the right and fitting name for our Sellers, since it was odd and quaint and all that. I liked the idea, but I said that that man might turn up and object. But Warner said it couldn't happen; that he was doubtless dead by this time, a man with a name like that couldn`t live long; and be he dead or alive we must have the name, it was exactly the right one and we couldn`t do without it. So the change was made. Warner's man was a farmer in a cheap and humble way. When the book had been out a week, a college-bred gentleman of courtly manners and ducal upholstery arrived in Hartford in a sultry state of mind and with a libel suit in his eye, and his name was Eschol Sellers! He had never heard of the other one, and had never been within a thousand miles of him. This damaged aristocrat's programme was quite definite and businesslike: the American Publishing Company must suppress the edition as far as printed, and change the name in the plates, or stand a suit for $10,000. He carried away the Company's promise and many apologies, and we changed the name back to Colonel Mulberry Sellers, in the plates. Apparently there is nothing that cannot happen. Even the existence of two unrelated men wearing the impossible name of Eschol Sellers is a possible thing.

- Mark Twain's Autobiography, Vol. 1, pp. 90-91.

Mark Twain's official biographer Albert Bigelow Paine offered this version of the story:

There are bound to be vexations, flies in the ointment, as we say. It was Warner who conferred the name of Eschol Sellers on the chief figure of the collaborated novel. Warner had known it as the name of an obscure person, or perhaps he had only heard of it. At all events, it seemed a good one for the character and had been adopted. But behold, the book had been issued but a little while when there rose "out of the vasty deeps" a genuine Eschol Sellers, who was a very respectable person. He was a stout, prosperous-looking man, gray and about fifty-five years old. He came into the American Publishing Company offices and asked permission to look at the book. Mr. Bliss was out at the moment, but presently arrived. The visitor rose and introduced himself.

"My name is Eschol Sellers," he said. "You have used it in one of your publications. It has brought upon me a lot of ridicule. My people wish me to sue you for $10,000 damages."

He had documents to prove his identity, and there was only one thing to be done; he must be satisfied. Bliss agreed to recall as many of the offending volumes as possible and change the name on the plates. He contacted the authors, and the name Beriah was substituted for the offending Eschol. It turned out that the real Sellers family was a large one, and that the given name Eschol was not uncommon in its several branches. This particular Eschol Sellers, curiously enough, was an inventor and a promoter, though of a much more substantial sort than his fiction namesake. He was also a painter of considerable merit, a writer and an antiquarian. He was said to have been a grandson of the famous painter, Rembrandt Peale.

- Mark Twain: A Biography, Albert Bigelow Paine, pp. 501-502.

THE REAL GEORGE ESCOL SELLERS

Paine was not far off base with the "real Sellers" family heritage. The real George Escol (no "h" in the spelling) Sellers was not the grandson of Rembrandt Peale. From his maternal lineage, Rembrandt Peale was his uncle and the noted American artist Charles Willson Peale was his grandfather. Charles Willson Peale (1741-1827) is best remembered as "Artist of the American Revolution." He was the patriarch of what became an extraordinary family of American painters which included his children Raphaelle (1774-1825), Rembrandt (1778-1860), Rubens (1784-1865), Titian Ramsay (1799-1885), with niece Sarah Miriam Peale (1800-1885), and nephew Charles Peale Polk (1767-1866). Charles Willson Peale also had a life-long interest in natural history and in 1786 opened a museum in Philadelphia. As a boy, young George Escol worked in his grandfather Peale's Philadelphia Museum and later became a member of its board of directors.

George Escol Sellers was born in Philadelphia on November 26, 1808. (And in another strange-name coincidence with Twain's character, the neighborhood George Escol was born in was known as Mulberry Court, located between Fifth and Sixth Street near the first United States Mint.) He was the son of Coleman Sellers (1781-1834) and his wife Sophonisba Angusciola Peale (1786-1859). From his paternal lineage, his grandfather Nathan Sellers (married to Elizabeth Coleman) was widely known in the United States as a crafter in the art of making wire paper molds. Coleman Sellers and Sophonisba Peale married in September 1805 and were the parents of at least six children: Charles Sellers, born in 1806; George Escol Sellers, born in 1808; Elizabeth Sellers, born in 1810; Harvey Lewis Sellers, born in 1813; Anna Sellers, born in 1824; and Coleman Sellers, born in 1827.

According to Escol Sellers's great nephew, Harold Sellers Colton:

George Escol Sellers received his curious middle name from a dream that his father had on the night he was born. He saw four men carrying a large bunch of grapes. This dream recalled the brook of Eschol from which Moses' henchmen carried back to Moses a bunch of grapes (Numbers XIII:23) "and they came unto the brook of Eschol and cut down from thence a cluster of grapes." (Harold Sellers Colton, "Mark Twain's Literary Dilemma and Its Sequel," The Arizona Quarterly, Vol. 17, Autumn 1961, pp. 229-232).

In addition to papermaking, Coleman Sellers became involved in manufacturing fine engines and his machine shop provided his sons with training in the mechanical arts. In 1832, at age twenty-four, George Escol spent several months in England studying papermaking machines. After returning to the United States, he married Rachel Brooks Parrish on March 6, 1833. When Coleman Sellers died in 1834, his sons continued the general machine work which included building two locomotives for the state railroad of Pennsylvania and machinery for the United States branch mints which were estabalished in North Carolina and Georgia. Following the depression of 1837, George Escol and his brother Charles relocated to Cincinnati where they organized the Globe Rolling Mills and Wire Works and invented a grade-climbing locomotive. Five children were born to George Escol Sellers and his wife Rachel. The couple also adopted an orphaned daughter of one of George's cousins. During the Civil War, the couple moved to southern Illinois on the banks of the Ohio River and George Escol experimented with methods of using swamp cane as paper stock. He became interested in the American Indian and collected artifacts and pottery from the Indian mounds in the Ohio Valley. He developed a skill in making arrowheads and specimens of his work were later displayed in the National Museum in Washington. Rachel died at Sellers Landing, Hardin County, Illinois on September 14, 1860. Of their five children, only one son survived her.

|

Mark Twain scholar Hamlin Hill has described George Escol Sellers's family background:

|

The Sellers locomotive from an advertisement in A. M'ELROY'S PHILADELPHIA DIRECTORY FOR 1839 |

REACTION TO AN INSULT

Thus, when Charles Dudley Warner persuaded Twain to name his character Eschol Sellers, an inventor of grand schemes that never materialized, the insult to one of America's prominent families was set in print. In spite of the variant spelling, George Escol Sellers, inventor, mechanical engineer, and author of Improvements in Locomotive Engines, and Railways (Cincinnati, 1849) took serious offense. Charles Dudley Warner and the real George Escol Sellers had a mutual friend in Dr. J. H. Barton, a resident of Lock Haven, Pennsylvania. In 1855 he may have been involved with Warner in the real estate firm of Barton and Warner in Philadelphia. (See Mark Twain's Letters, Vol. 5, 1872-1873, p. 7).

When Dr. J. H. Barton discovered the name of his friend Escol Sellers (spelled "Eschol") in a salesman's prospectus for Warner and Twain's upcoming book, he began a series of correspondence between himself, Warner, and Escol Sellers. This correspondence survives in the files of the American Philosophical Society Library, Philadelphia. Dr. Barton protested to Warner in December 1873 about the use of the name of his friend George Escol Sellers. Warner replied to Barton and enclosed a message to be forwarded along to Sellers disavowing any connection between the fictitious Colonel Sellers and the true to life George Escol Sellers. Sellers replied in an irate letter to Warner on January 1, 1874 demanding that a disclaimer be issued. Warner replied on January 7, 1874 agreeing to issue a disclaimer. On January 13, 1874 Warner again wrote to Sellers that the plates of The Gilded Age would be changed and another name substituted for "Eschol." On January 15, 1874 Warner wrote to Sellers again regarding the name substitution in the printing plates. Warner next telegraphed Sellers on both January 17 and 19 arranging a meeting in the Hartford offices of the American Publishing Company. The meeting took place on January 20. There is no evidence that money changed hands at that meeting. Sellers was told that 2000-3000 copies of The Gilded Age not corrected would be recalled and that he would be sent a corrected copy. However, fifteen month later, Sellers still had not received a corrected copy and to add insult to injury, the Evansville, Indiana Courier of March 7, 1875 contained a practical joke story identifying Escol as the real Col. Sellers in The Gilded Age.

The author of the Evansville Courier article was J. A. Lemcke. In 1905 he recalled the joke in his book Reminiscences of an Indianian. I am indebted to Dave Thomson for calling my attention to this passage and providing a copy of the text:

|

How I got into Trouble with the same Colonel Sellers Caseyville on the lower Ohio, ... was the home of my friend Mr. Sam Casey, a brother-in-law of General Grant. Just opposite and across the river from this Kentucky town, in the knobs of Hardin county, Illinois, is "Sellers' Landing." Here lives, or did live, when alive, Mr. Sellers, the Eschol Sellers of Mark Twain's book. He was, as described by Mr. Clemens, a very handsome man of aristocratic bearing and appearance, kind-hearted and very courteous. Sprung from a distinguished old Philadelphia family, he had been educated in mechanical engineering, and, as an inventor of a process of making paper from cane, had selected the city for the erection of a hundred thousand-dollar paper mill. When the government established a post office at his place, our line of boats served it regularly, and it was thus that I came to know the silver-haired, genial old gentleman who was the embodiment of the milk of human kindness in its condensed form. It was the comical sound only of the unusual front name of Mr. Sellers which attracted the authors; but had they known the peculiarities of the man as well as I knew them they would not have given up that name without a struggle. No better pattern for their hero could have been found anywhere. The one-hundred-thousand-dollar paper mill, with "millions it," that he had erected, in which the cane from the near-by river bottoms was to be shot out of big guns to tear asunder its fiber, proved it. The mill, idle and abandoned for many years stood on the hillside above the river, a monument to impracticability and failure. Some years later, at the suggestion of my friend Gil Shanklin, the owner and editor of the Evansville Courier, I wrote up for his paper one day, in a rollicking editorial, the foregoing facts, and embellished the skit by referring to the passage in "The Gilded Age," in which Colonel Sellers tells his young friend Hawkins that he and the Rothschilds are going to buy up one hundred and thirteen wildcat banks in Ohio, Indiana, Kentucky, Illinois and Missouri, and make forty millions by it; and also touched on the well-known eye water scheme. This editorial, with its thinly-veiled allusions, naturally gave offense

to Mr. Sellers, who much disliked that kind of notoriety. When in time

it leaked out from the sanctum of the paper that I had been the perpetrator,

I also, like Clemens and Warner, was threatened with a lawsuit, which

I am now satisfied I richly deserved. It was averted only by sand-papered

apologies and friendly intercessions from others. |

According to Hill, "Sellers was going to sue the Evansville Courier in federal court and get Clemens, Warner, Bliss, and everybody else he could, on the stand. But something persuaded him to change his mind. Perhaps it was his friends in Philadelphia; perhaps it was Warner's absence in Europe. Whatever the reasons, the suit was apparently never brought, and George Escol Sellers had three years of relative tranquillity" (Hill, 112). On September 6, 1878 the St. Louis Globe-Democrat reprinted a story from the New York Sun stating that Colonel Eschol Sellers had received $2,000 over the unfortunate name incident. Sellers wrote his friend Dr. Barton that he had made no demand of money over the incident. Barton tried to calm his friend and attributed the story to publicity gimmicks and gossip and he recommended Sellers not stir the controversy with a reply. George's brother Coleman Sellers also urged him to ignore the article and there is no record that he did otherwise.

NO ESCAPE FROM TWAIN'S PORTRAYAL

In his 1961 article for The Arizona Quarterly, Harold Sellers Colton, Professor Emeritus of Zoology of the University of Pennsylvania, and Director of the Museum of Northern Arizona from 1928-1958 and one of Arizona's most distinguished citizens gave a personal family perspective of the negative impact The Gilded Age had dealt his ancestor. According to Colton, Sellers had moved to southern Illinois with investment money from residents of Philadelphia and opened a coal mine at Sellers Landing, Hardin County on the Ohio River. He hoped to sell coal to steamboats on the river. But many boat owners had not converted their boilers to coal -- wood being plentiful on the river banks. The Sellers coal project failed.

At the time The Gilded Age was published, Escol was engaged in building up industries at Sellers Landing to make a market for the coal. Needing considerable capital, he went for further support to capitalists in Philadelphia who had supplied funds for the original coal operation. As these persons had been getting little return for their money they were quite disgruntled.

In the meantime Mark Twain had made The Gilded Age into a popular play which was acted in many cities of the country. About this time he wrote another book, The American Claimant, in which Col. Sellers was also a leading character. Notwithstanding the fact that the name of Col. Sellers had been changed to Mulberry Sellers, at Sellers Landing people believed that Escol Sellers was the prototype of Col. Mulberry Sellers. Some people were pointing him out as Col. Sellers. These reports reached the financial circles in Philadelphia which made the future development of industries at Sellers Landing impossible. That he was the prototype of the fictional Col. Sellers dogged him all the rest of his life. His career was greatly injured. (Colton, pp. 231-232.)

Following his retirement from business, George Escol Sellers, along with his sister Anna and adopted daughter moved to Mission Ridge in Chattanooga, Tennessee. He wrote a series of 48 articles for American Machinist magazine -- a series that spanned eleven years. His first contribution appeared in the June 7, 1884 issue and the last appeared August 29, 1895. Many of these articles were collected and published by the Smithsonian Institution in 1965 in Early Engineering Reminiscences (1815-40) of George Escol Sellers. The editor of the collection described George Escol Sellers's writings:

This book describes the development of machines and mechanical skills in the United States during the first half of the 19th century. It illuminates a facet of our technological heritage that is little known despite its essential importance to our understanding of the emergence of the United States as an industrial nation. Here the reader will meet many of the craftsmen and engineers who devised and developed the machines and techniques that made possible the growth of an industrial complex. He will find many fresh details of surprisingly sophisticated tools and skills that existed during an age that he has been taught was mechanically uncouth. ...Written with rare precision, perception, detachment, and good humor, these reminiscences have freshness and vigor that commend them to every interested reader (Eugene S. Ferguson, Early Engineering Reminiscences (1815-40) of George Escol Sellers, xi).

However, when Sellers died in 1899 his obituaries continued to mention the character of Mark Twain's "Mulberry Sellers."

|

From The Atlanta Constitution, January 2, 1899, pg. 3 DEATH OF AN OLD ENGINEER Chattanooga, Tenn., January 1. -- (Special.) -- George Escol Sellers, one of the most noted engineers of his day, died at his residence on Mission Ridge this morning at 11 o'clock, in the ninety-first year of his age. The deceased was born in Philadelphia November 26, 1808. In 1844 he removed to Cincinnati, leaving that city shortly after for southern Illinois, where he became interested in coal lands and coal mining with the late Samuel J. Tilden. He is said to have made the first survey for a railroad through Georgia and Tennessee about the year 1849. He was one of the oldest locomotive builders in the United States, having built locomotives for the government years before the war. Mr. Sellers came to this city in 1888. He had the largest collection of Indian relics of any single individual collector in this section of the country. It has been said that he was the original of Mark Twain's "Mulberry Sellers," but he indignantly denied that imputation and resented any allusion to such being the facts. He was a brother of Coleman Sellers, the distinguished engineer of Philadelphia, and is a grandson of the celebrated artist Charles Willson Peale. |

A lengthy profile of Escol Sellers printed two years after his death focused on his arrowhead collection and also mentioned the Mark Twain and Colonel Sellers connection:

|

From The Atlanta Constitution, September 8, 1901, pg. A1 The Original Col. Mulberry Sellers Until about two years since, there lived in a comfortable home just south of the tower which marks the site of Bragg's headquarters during the battle of Missionary Ridge, one of the most interesting characters that it was ever the writer's pleasure to meet. His name was George Escol Sellers, the character made famous by Mark Twain. He was born in Philadelphia in November 1808. More than fifty years ago he was engaged in civil engineering in Tennessee, and knew more about that state, its past history, its anthropology, archaeology, etc., than most of the most intelligent natives, although he had been a citizen at the time of his death only about twelve years. After we had talked for half an hour about those old days my friend informed him that I would like to look at his curiosities. "All right," said he, "I will go with you to the other room." Arising with some difficulty, he accompanied us to the hall, where he took his hat and cane. "I am beginning to get a little feeble," he remarked as he took up the cane; "nine years ago I could easily walk 18 miles every day. Now I seldom go farther than the tower down there. But come on, we will to the other house." What he had first designated as the other room was, in fact, a separate house, large enough for the accommodation of quite a family, I should say. Unlocking the door he bade us precede him, with a courtly gesture, and declining my friend's assistance in going up the stairs. "Walk in," said he with a smile which seemed to me to be more of sadness than of pleasure; "this is my den." And such a den it was as one seldom has opportunity to enter. It was a combined student's room, artist's studio, engineer's office and anthropological museum. Good books of all kinds were upon the shelves. Upon the walls, neatly mounted, was the finest private collection of Indian relics that I ever saw. Arrowheads were the predominant feature of the collection. The most of them were genuine. But the most interesting of all, to me, was one card of them, mounted like the others, and honestly labeled as artificial. They were all of Mr. Sellers' own make. No one save an expert could have told but that aboriginal Indians made them, unless suspicion may have been excited by the strange materials of which many of them were made. Some were of very common soft stone. Some were of the hardest flint, and some were of glass. "I make them," said Mr. Sellers, "simply to show that arrow-points can be made of any substance which is susceptible to concordial fracture, and also to prove that the Indians made them by pressure simply, and not, as usually contended by quick blows." He then entered upon a discussion of the implements with which the Indians made their arrow-heads. He insisted that the finer work, showing the deeper cuts, must have been done with copper implements, and not, like the most of the heads, with sharp-pointed bones. He took a cooper implement, which he called his "universal tool," and showed me how the fractures were made, preserving a uniform angle. The material that he used was an imperfect arrowhead of genuine origin and the stone was very hard. He flaked off pieces by simple pressure without leaving noticeable change in the general character of the cutting and angles. This universal tool was a simple copper wire about the diameter of a slate pencil inserted into a tube; the tube was fastened into the end of a wooden handle and held in place by a thumbscrew. With this the wire could be adjusted so as to leave projecting whatever length was needed for the work in hand. According to Mr. Sellers' theory the Indian arrow point maker held his material tightly in one hand, while with a sharpened bone, fastened to his thumb with a thong, he sharply pressed upon the stone wherever he wanted to break it away. Thus with but little trouble he flaked it and shaped it to suit his purposes and tastes. As before stated, for the finer work Mr. Sellers believed that copper implements were used. "Arrow making was an art," said he "handed down from Indian to Indian, just as blacksmithing and other arts have been handed down from white man to white man." I have been told that he was often called upon to make arrow heads for noted experts throughout the country, and that they were often unable to distinguish his work from that of Indians, when the materials which he used were the same in character as that of which the genuine Indian work was made. It was evident that Mr. Sellers had been accustomed to wealth, and his circumstances were apparently easy at the time of my visit. It is related of him that he at one time advanced a large sum of money to complete a railroad. Not only did he advance something like $80,000, but he gave his professional services, expecting to be in the organization when the road was completed and profit by his enterprise. But, as often happens, no sooner was the road ready for operation than a reorganization was effected and the chief promoter was left out in the cold. To his appeals that he be reimbursed the new management always answered in substance: "This organization has nothing whatever to do with it, and we can do nothing for you." Two of the directors, however, relented, or else they made a bit more of honesty in their makeup than the others, from the first, and through their influence he was at last offered $20,000 if he would release all claim. When the message was received he was at work upon some roofing material. Taking up a piece of the heavy roofing paper and a marking brush he lettered the following reply: "As corporations have no souls to be damned and no corporal bodies to kick, your proposition is accepted." The president was so impressed by the message that he became the active friend of its writer and gave him subsequent opportunity to recoup his losses by profitable service to the corporation. Mr. Sellers was the original of Mark Twain's "Colonel Mulberry Sellers," but that was a rather sore experience to him, and he did not often refer to it. Sometimes, however, when talking to friends he recurred to it in very plain terms. He greatly disliked to be called Colonel Sellers and his friends usually cautioned people who contemplated visiting him to studiously avoid that title when addressing him. It is understood that he sued the publishers of Mr. Clemens' book for the characterization of him which occurred in the first edition and recovered substantial damaged. After that the objectionable matter was expunged. |

So the question remains -- Why did Twain disguise the name of the person who was the true inspiration for Colonel Sellers? Henry Watterson (1840-1921) editor of the Louisville (KY) Courier-Journal also shared a blood tie to Twain's cousin James J. Lampton who was the son of Lewis Lampton and Jennie Morrison. (Jennie's sister Mary Morrison was Watterson's maternal grandmother.) Watterson's description of James Lampton offers perhaps the best explanation: "A second Don Quixote in appearance and not unlike the knight of La Mancha in character, it would have been safe for nobody to laugh at James Lampton, or by the slightest intimation, look or gesture to treat him with inconsideration, or any proposal of his, however preposterous, with levity ("Marse Henry": An Autobiography, Henry Watterson, p. 121-122). Thus, Twain's family was spared embarrassment when he unwittingly agreed to change the character's name, a character that is best described by Mark Twain's close friend William Dean Howells:

We owe to The Gilded Age a type in Colonel Mulberry Sellers which is as likely to endure as any fictitious character of our time. It embodies the sort of Americanism which survived through the Civil War, and characterized in its boundlessly credulous, fearlessly adventurous, unconsciously burlesque excess the period of political and economic expansion which followed the war. Colonel Sellers was, in some rough sort, the American of that day, which already seems so remote, and is best imaginable through him.

- My Mark Twain, William Dean Howells, p. 173.

____

REFERENCES

American Philosophical Society Library, Philadelphia internet

website: <http://www.amphilsoc.org/library/mole/s.htm>

March 20, 2006.

Also: <http://www.amphilsoc.org/library/mole/r/rogmanuscriptmaps.htm#boxfolder42>

March 20, 2006.

Ancestry.com internet file: <http://awt.ancestry.com/cgi-bin/igm.cgi?op=GET&db=:3174364&id=I08367> March 20, 2006

Colton, Harold Sellers. "Mark Twain's Literary Dilemma and Its Sequel." The Arizona Quarterly, Vol. 17, Autumn 1961, pp. 229-232.

"Death of an Old Engineer," The Atlanta Constitution, January 2, 1899, pg. 3.

Ferguson, Eugene S., Early Engineering Reminiscences (1815-40) of George Escol Sellers. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, 1965.

Hill, Hamlin. "Escol Sellers from Uncharted Space: A Footnote to The Gilded Age," American Literature, Vol. 34, No. 1 (Mar. 1962), 107-113.

Howells, William Dean. My Mark Twain. Dover Publications, 1997.

Lemcke, J. A. Reminiscences of an Indianian. Indianapolis: Hollenbeck Press, 1905.

Paine, Albert Bigelow, ed. Mark Twain's Autobiography, Vol. 1. Harper and Brothers, 1924.

Paine, Albert Bigelow. Mark Twain: A Biography. Harper and Brothers, 1912.

Rasmussen, R. Kent. Mark Twain A to Z. Oxford University Press, 1995.

Salamo, Lin and Harriet Elinoir Smith, eds. Mark Twain's Letters, Vol. 5, 1872-1873. University of California Press, 1997.

Twain, Mark. The American Claimant. Oxford University Press, 1996.

Twain, Mark and Charles Dudley Warner, The Gilded Age. Oxford University Press, 1996.

Twain, Mark, Life on the Mississippi. Oxford University Press, 1996.

Watterson, Henry. "Marse Henry": An Autobiography. New York: George H. Doran Company, 1919.

Wiltse, Henry M., "The Original Col. Mulberry Sellers," The Atlanta Constitution, September 8, 1901, pg. A1.