|

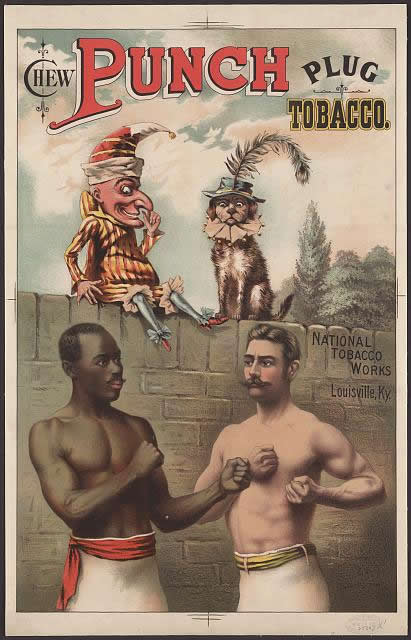

Boxing poster from Library of Congress Prints and Photorgraphs Division. |

_____

On Saturday, January 27, 1894, Mark Twain, along with Henry H. Rogers and architect Standford White, attended the boxes matches at Madison Square Garden. Stanford White introduced Mark Twain to boxer James J. Corbett in Corbett's dressing room. Twain wrote Livy:

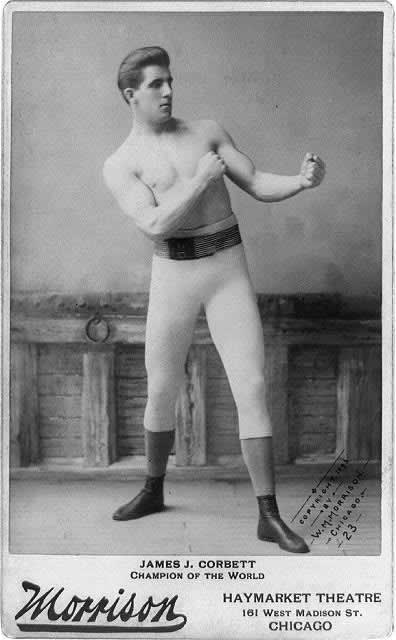

Photo from Library of Congress Prints and Photorgraphs Division. |

By 8 o’clock we were down again and bought a fifteen-dollar box in the Madison Square Garden (Rogers bought it, not I,) then he went and fetched Dr. Rice while I (went) to the Players and picked up two artists -- Reid and Simmons -- and thus we filled 5 of the 6 seats. There was a vast multitude of people in the brilliant place. Stanford White came along presently and invited me to go to the World-Champion’s dressing room, which I was very glad to do. Corbett has a fine face and is modest and diffident, besides being the most perfectly and beautifully constructed human animal in the world. I said:

“You have whipped Mitchell, and maybe you will whip Jackson in June -- but you are not done, then. You will have to tackle me.”

He answered, so gravely that one might easily have thought him in earnest:

“No -- I am not going to meet you in the ring. It is not fair or right to require it. You might chance to knock me out, by no merit of your own, but by a purely accidental blow; and then my reputation would be gone and you would have a double one. You have got fame enough and you ought not to want to take mine away from me.”

Corbett was for a long time a clerk in the Nevada Bank in San Francisco.

There were lots of little boxing matches, to entertain the crowd: then at last Corbett appeared in the ring and the 8,000 people present went mad with enthusiasm. My two artists went mad about his form. They said they had never seen anything that came reasonably near equaling its perfection except Greek statues, and they didn’t surpass it.

Corbett boxed 3 rounds with the middle-weight Australian champion --

oh, beautiful to see! -- then the show was over and we struggled out

through a perfect wash of humanity |

_____

|

CHICAGO DAILY INTER OCEAN, January 20, 1888, p. 5 TWAIN IN THE RING. ATHLETIC EXPLOITS. San Francisco Chronicle: Mark Twain has not lacked celebrity in his time. His life and adventures have been industriously written, both by himself, and others. Everyone knows about his exploits as a newspaper reporter, and his experiences as a river pilot; but the fact has hitherto been lost to the world that at one time he had aspirations to be a boxer. The secret leaked out the other day in a bathing establishment at North Beach, where half a dozen well-known and venerable pioneers were gathered to celebrate the Christmas week by a plunge in the uninviting waters of the bay. A cheerful Turkish bath would, perhaps, have been more beneficial to these veterans of the spring of '49, but to evade their accustomed plunge in the chilly bay would be an acknowledgment that old age was beginning to cool their blood. This to the average pioneer is the most depressing confession that can be extracted, and so the six gray-haired and rheumatic old relics of another age sat and shivered in the bath-house after their plunge. The timely discovery of a bottle of old bourbon in one of the lockers helped to restore their circulation. As the bottle went round the tongues of the pioneers commenced to wag of the events of a quarter of a century ago. One of the pioneers suggested a bout with the boxing gloves to more thoroughly remove the effects of their aquatic indiscretion. "Oh, there's no use in your boxing," said another old veteran. "What do you want boxing? Why, you were never able to LICK EVEN MARK TWAIN" This reference brought up the humorist's exploits as a would-be athlete, and the pioneers talked over them as long as the bottle held out. "I never saw a man who was of such little account as a boxer as Mark Twain," said one pioneer who seemed to have been more familiar with the great humorist's aspirations than anyone else. When Twain was working on the newspapers as a reporter, continued the pioneer, the Olympic Club had a set of very lively boxers. Boxing was all the rage then. Several men that have since become bankers, eminent lawyers, and railroad magnates used to put on the gloves in the old club room and keep things lively. Twain was very ambitious to become an athlete. After he had been robbed by footpads on the Divide, outside Virginia City, an experience he has described in "Roughing It" he made up his mind to practice boxing. He thought, I guess, that if he could have used his fists to good effect he would not have had such an unpleasant experience. Any how he resolved to become an athlete, and confided his aspirations to John McComb, now the Warden of San Quentin Penitentiary. John was not a General of militia at that time, and having less dignity to carry than now was very handy with his fists. Twain, who was totally devoid of athletic qualities, looked on McComb as a sort of John L. Sullivan, or rather Tom Hyer, for the latter was the pugilistic wonder of those days. McComb advised Twain to improve his muscles by wrestling, and the two of them spent a good many evenings in that way. The pewter pots and glasses they wrestled with, however, were too much for THE RISING HUMORIST, and while the future General grew rosy and rotund on the exercise, Twain kept getting more spider-like every day. McComb did not want to let him change his exercise, as Twain's droll talk when he was three sheets in the wind was very amusing; but finally Mark rebelled and announced that he would try another physical adviser. Some one advised him to go to Frank Wheeler, well known then as a general athlete and professor of the manly art. Frank was accustomed to teaching sluggers, and his energetic instruction had such a depressing effect on Twain's jaw that he abstained from beefsteak for a month after his first lesson He next tried Bill Clarke, also a noted boxer, and here he met with more success for a while. One evil day, however, he was induced to have a bout with John Lewis, the ex-Supervisor. Lewis was noted among the amateurs as the owner of a very ugly right hand that had a knack of catching them, with the force of a trip-hammer, under the ear when they least expected it. Lewis was somewhat sensitive of his athletic reputation, and if he thought any man was setting-to with him to test his ability, he generally let him have the best that he was able to give. Poor Mark was in a quest only of innocent practice, but Denis McCarthy, a popular and able journalist, who liked to have a joke at Twain's expense, informed Lewis that he had better look out for his opponent. "He's knocked out a couple of light-weights on the Comstock," said the jocose editor, "and he's just trying himself against a California heavy-weight, so don't let him make any reputation on you, or he'll go back and blow about it all through Nevada." "He will, eh!" remarked the heavy-weight, and he went into the dressing-room with a formidable frown to prepare for the set-to. Twain came out with a loose and thick woolen shirt, which concealed his muscular deficiencies and gave him an unusually burly aspect. Notwithstanding this fact, the amateur slugger was by no means impressed with the humorist's appearance, and gave him what he thought A LIGHT SLAP under the ear to test his mettle. The result was disastrous. The aspiring humorist threw a double somersault and, alighting on the back of his neck, lay at full length on the floor. The crowd rushed over, and Lewis, who was the first, picked him up. "You're not hurt, are you? Why, that was nothing," said the alarmed boxer, soothingly. The humorist only replied with a groan. "Shall I send for a doctor for you?" asked Editor McCarthy. "Send for an undertaker, Denis," gasped the damaged humorist. "What's the matter with you?" inquired the now alarmed journalist. "I'll be able to tell you as soon as my neck is set," replied the humorist, picking himself up and dragging himself back to the dressing room. He remarked to McCarthy when he came out again, with his handkerchief wrapped around his damaged neck. "If I could hit like that fellow I'd hire myself as a pile-driver on the city front and make $500 a day." Twain next showed up as a boxer in the Olympic Club, where old Joe Winrow, John Morrissey's and Tom Hyer's ex-trainer, was teaching the manly art. Winrow was a professional pugilist, who had fought one of the longest ring battles on record, but he was very gentle as a teacher, and Twain blossomed out as quite a boxer. Winrow, like the celebrated Bendigo, became a very religious man after he had abandoned active pugilism, and used to read the Bible every morning as regularly as he took his breakfast. Sometimes when teaching, however, the old spirit would rise in the reformed pugilist and he would swing in his right hand with unchristian fervor. Twain had a holy horror of the old pugilist's right, and whenever he observed dangerous enthusiasm in his teacher's eye would shout out: "Joe, remember the Scriptural instruction. 'Don't let your right hand know what your left is doing?'" The old man used to laugh, and when the lesson was over would sit down and smoke one of the two-bit cigars that the humorist always brought along to ingratiate himself with his tutor. THE DESPERATE BATTLE between Twain and Moore, the bookseller, will long be remembered as one of the sensational events of the old club. Moore was a feather-weight champion and tipped the scales somewhere in the neighborhood of ninety pounds. He was very pugnacious, a quality which Twain did not possess. The humorist, however, had much the best of the match in weight, and, besides, was seconded by that accomplished mentor, Philo Jacoby; Stewart Menzies was referee, and Frank Lawton was timekeeper. As much as $1.50, besides several drinks and cigars, was wagered on the contest. Moore, who meant mischief, wanted an eighteen-foot ring, while Twain wanted the orthodox twenty-four-foot ring. John McComb suggested, as the best means of settling the dispute, that each man should be allowed the ring that he wanted, and two rings were accordingly chalked out on the floor -- a large one of twenty-four feet and a smaller one inside it of eighteen feet. This ingenious arrangement entailed unexpected trouble, for after the first round Twain insisted on staying in his own corner and having Moore restrained from crossing the eighteen-foot frontier line. He called upon the referee to issue a writ of injunction against his antagonist to keep him inside the eighteen-foot chalkmark, and finally, finding the Supreme Court, as it were, against him, jumped the ring altogether and claimed the match on a breach of contract. The spectators, who rolled on their chairs and benches as the amusing contest proceeded, were more exhausted at the close than the combatants, who never after appeared in any ring. After his first and last ring fight Twain devoted himself to fencing, which he concluded was a much more pleasant road to athletic excellence than the pugilistic pathway. He practiced assiduously for some time, but he could never master the intricacies of the art, and after William Norris doubled up a foil on his ribs one day with a thrust that would have gone through a pine board had the point been without a protecting button, Twain gave up athletics altogether. "I've concluded, John," said he to McComb, that it's not healthy to have too much muscle anywhere, even on your tongue, so I've quit." "He hasn't lost anything by the muscles of his tongue, however, " remarked the pioneer, as he looked wistfully at the now empty bottle, and with the other veterans started up town. |

Related item: "Mark Twain Takes a Lesson in the Manly Art" by Dan DeQuille

Quotations | Newspaper Articles | Special Features | Links | Search