|

Mark Twain Has Lost a Black Cat. Have you seen a distinguished looking cat that looks as if it might be lost? If you have take it to Mark Twain, for it may be his. The following advertisement was received at the American office Saturday night: A CAST LOST - FIVE DOLLARS REWARD for his restoration

to Mark Twain, No. 21 Fifth avenue. Large and intensely black; thick,

velvety fur; has a faint fringe of white hair across his chest; not

easy to find in ordinary light. |

A TALK WITH MARK TWAIN'S CAT, THE OWNER BEING INVISIBLE

[Note: This was an unsigned article written by Zoe Anderson Norris. The story

of how she wrote this article is featured below.]

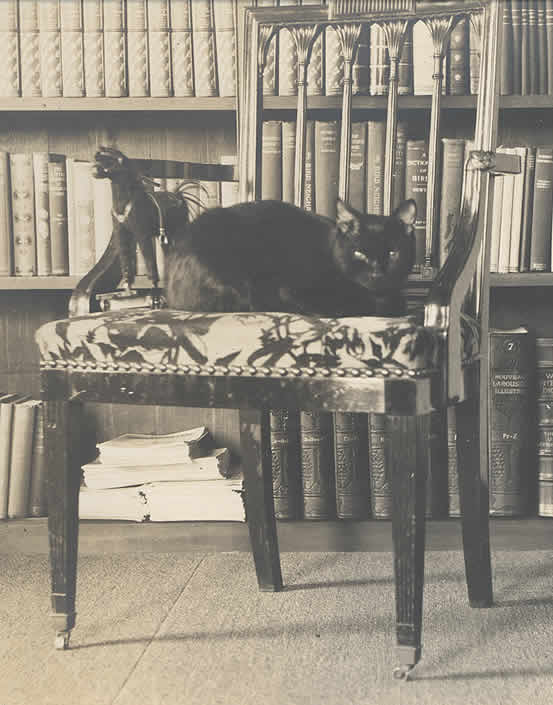

Photo of Bambino

by Mark Twain's daughter, Jean Clemens

from the archives of the Mark Twain Papers, University of California, Berkeley.

Mark Twain had lost his cat. Consumed with an attack of wanderlust, Bambino had fled from home and roamed for a day and a half. The humorist had offered a reward of $5. Then his secretary, Miss Lyon, had met Bambino on University Place and haled him home.

It was all in the papers.

Failing to understand why it shouldn't be in the papers some more, a woman from THE TIMES had called at the Clemens mansion, 21 Fifth Avenue.

A man with china blue eyes and a white waistcoat opened the door for her. He opened it just half way.

Upon her request to see Mr. Clemens, he gave a start of surprise, frowned, and said:

"Mr. Clemens is asleep."

It was then 1:30 in the afternoon.

"When can I see him?" asked the woman.

"I will find out," said the servant, and shut the door upon her while he did so.

By and by he reopened it.

"He may see you," he told her, "if you come back at 5 o'clock."

It was a beautiful sunshiny day, but the woman went home, stayed indoors to rest up for this interview, and at 5 o'clock again sauntered toward the Clemens mansion.

The same man appeared. He wore the same waistcoat. He had, likewise, the same blue eyes.

"Mr. Clemens is not in now," he said, "but his secretary might see you."

"Very well," responded the woman, and stood outside the shut door once more while he searched for the secretary.

As she gazed upon Fifth Avenue, gay in the sunshine with automobiles and carriages and people enjoying themselves, she wondered vaguely if thieves were in the habit of infesting the Clemens mansion; if that was the reason they were so particular about the door.

Then it opened cautiously and the servant said:

"You may come in."

Precious privilege. The woman went in and stood in the hall as if she were a book agent. There were chairs, but she was afraid to sit down.

Presently the secretary, a nice little woman with brown eyes and old-fashioned sleeves, came down the stairs and asked her what she wanted.

"I want to see Mr. Clemens about the cat," replied the woman.

"Mr. Clemens never sees anybody - I mean any newspaper people. Besides, he is not at home."

"Then," said the woman, "may I see the cat?"

"Yes," nodded the secretary, "you may see the cat," and she ran lightly up the long stairway and came down soon with Bambino in her arms, a beautiful black silent cat with long velvety fur and luminous eyes that looked very intelligently into the face of the woman.

The secretary and the woman then sat down on a bench in the hall, and talked about the cat. The cat listened but said nothing.

"We were terribly distressed about him, cooed the secretary. "He is a great pet with Mr. Clemens. He is a year old. It is the first time he has ever run away. He lies curled up on Mr. Clemens's bed all day long."

"Does Mr. Clemens breakfast at five o'clock tea and dine on the following day?" asked the woman.

"Oh, no. He does all his writing before he gets up. That's why he gets up at 5 o'clock. Bambino always stays with him while he writes."

"I should consider it a great privilege," smiled the woman, "to breathe the same atmosphere with Mr. Clemens for about three minutes. Don't you think if I came back at 7 you might arrange it?"

"I will try," promised the secretary, kindly.

At 7, therefore, the woman toiled up the dark red steps and rang the bell. The china-eyed man with the white waistcoat opened the door, disclosed one eye and the half of his face, said abruptly, "Mr. Clemens doesn't wish to see you," and slammed the door.

The woman walked slowly down the red steps and looked up Fifth Avenue, wondering whether she would walk home or take a car.

Fifth Avenue was very beautiful.

Purplish in the dusk, it was gemmed with softly gleaming opalescent electric balls of light.

It was, moreover, admirably bare of people.

She concluded to walk home.

She was about to start forward when she became aware of a furry gentle something rubbing against her skirts.

She looked down, and there was Bambino, purring at her, looking up at her out of his luminous cat eyes.

The man at the door had shut him out, too!

She took him in both hands and lifted him up. He nestled against her shoulder.

"I don't like to prejudice you against the people you have to live with, Bambino," she said. "It seems they will make you live with them. But they weren't so nice. Were they? They might have told me at the start he wouldn't see me. They needn't have made me lose all the sunshine of to-day. You can't bring back a day and you can't bring back sunshine.

"You wouldn't have treated me like that, would you?"

Bambino purred musically in his earnest assurance that he would not.

"I suppose you heard it all," she went on, "and you sympathized with me. You are awfully tired yourself. I can see that. If you were a Parisian cat we'd call it ennuid, that expresses it better, but we'll let it go at tired. You are. Aren't you? Or you wouldn't have run off."

Bambino sighed wearily and half closed his eyes.

"It's a pretty rarefied atmosphere, I imagine, for a cat," she reasoned. "I don't blame you for wanting to get out with the common cats and whoop it up a little. Any self respecting cat would rather run himself in a gutter or walk the back fence than sit cooped up the livelong day with a humorist. You can't tell me anything about that. It's a deadly thing to see people grind out fun. I used to know a comic artist. I had to sit by and watch him try to match his jokes to pictures!

She clasped Bambino closer and caught her breath in a sigh.

"I don't blame you one bit for running off," she reiterated. "I can imagine what you must have suffered. Shall we walk along a little on this beautiful street that's so wide and empty now of people?" politely. "I get as tired as you do sometimes of people, Bambino. They are not always so nice. There are a lot of times that I like cats better."

Bambino curled himself up in her arms and laid an affectionate paw on her wrist by way of rewarding her.

She walked on, fondling him.

"I've the greatest notion," she confided presently, "to run off with you and paralyze them. It would serve them right. How would you like, Bambino, to come and live with me in my studio?"

Bambino raised his head and purred loudly against her cheek to show how well he would like it.

"Now, I want to tell you exactly how it will be. I want to be perfectly fair with you. If you come with me you must come with your eyes open. Maybe you won't have half as soft a bed to lie on, but you won't have to lie on it all day long. I'll promise you that. In the first place, it masquerades as a couch full of pillows in the daytime, and in the second place I've got to get out and hustle if I want to eat. Not that I mind hustling. I wouldn't stay in bed all day long out of the sunshine if I could. And you mayn't have as much to eat either, but if you get too hungry there are the goldfish - and the canary wouldn't make half a bad meal. I am pretty fond of both, but I am reckless to-night somehow. You'll be welcome to them."

Bambino licked his chops preparatorily.

"There are a good many little things you are apt to miss. The studio isn't as big as a house by an means, but you'll have all out doors to roam in. I'll trust to your coming home of nights because you'll like it there," she concluded confidently.

"And you'll be rid of the man at the door for good and all. Tell me, now, doesn't he step on your tail and 'sic' the mice on you when they are all away?"

Bambino groaned slightly, but he was otherwise noncommittal.

"I knew he did. He looks capable of anything. He's not as wise as he looks, though. He may not know it, but I push the pen for the tallest newspaper building in the city, the tallest in the world, I think. I'll take you up to the top of that building of mine, and let you climb the flag pole. Then if there should happen to be another cat on the Flatiron Building there'd be some music, wouldn't there, for the rest of the city? And they couldn't throw that flatiron at you anyway, could they? Want to go?"

Bambino put both paws around her neck, and purred an eloquent assent.

"You talk less than anybody I ever interviewed," remarked the woman, "but I think I know what you mean."

She pressed his affectionate black paws against her neck and hurried up the avenue, looking back over her shoulder to see that nobody followed.

She almost ran until she got to the bridge over the yawning chasm near Sixteenth Street. Then she stopped.

Bambino looked anxiously up to see what was the matter.

But turned deliberately around.

Bambino gave a long-drawn sigh. He looked appealingly up at her out of his luminous eyes.

"I reckon I won't steal you, Bambino," she concluded, sadly. 'I'd like to, but it wouldn't be fair.

"In the morning he'd be sorry. Maybe he couldn't work without you there, looking at him out of your beautiful eyes. You don't have to hear him dictate, too, do you Bambino? If I thought that! *** But no. There is a limit. He's had his troubles, too, you know. He's bound to be a little lenient. The goose hasn't always hung so high for him. Of course you don't remember it, but he had an awful time establishing himself as the great American humorist. Couldn't get a single publisher to believe it. Had to publish his 'Innocents Abroad' himself. Just said to the American public, 'Now, you've got to take this. It's humor,' and made them take it. Held their noses. That was a long time ago. Couldn't do it to-day. Not with 'Innocents Abroad.' The American public is getting too well educated. Who ever reads 'Innocents Abroad' now? Not the rising generation. You ask any boy of to-day what is the funniest book, and see if he doesn't say 'Alice in Wonderland'?

"Still, for an old back date book, that wasn't half bad. He has never written anything better. It must give him the heartache to see it laid on the shelf. I suppose you must hear these things discussed, but not this side of them, perhaps. No. Naturally no. They don't make you read their books, they can't, but you must have to hear about them. *** Life is hard! But I must take you back. We mustn't do anything at all to hurt his feelings."

Bambino was fairly limp with disappointment. He had set his heart on the top of The Times Building flagpole. He had almost tasted the canary, to say nothing of the goldfish. He hadn't the heart to purr any longer. He paws fell from the woman's neck. She had to carry him like that, all four feet handing lifeless, his head drooping.

"And there's another thing, Bambino," she continued, as they went along. "I don't want anything I said about his having to establish himself as a humorist to disillusion you or make you more dissatisfied than you are. All humorists are like that. They have to establish themselves. Why, wasn't I in London when Nat Goodwin produced his 'Cowboy and the Lady' at Daly's? Couldn't I hear people he had planted all over the audience that first night explaining that he was a humorist, and the play was intended to be funny? Certainly. But it didn't work that whirl. Those English people are more determined than we are. They wouldn't stand for it. He had to take the play off.

"Your master happened to catch us when we were young and innocent. He deserves a lot of credit for bamboozling us. You ought to admire him for it. I do."

They were nearly home by now. Bambino managed to emit another purr. It was like a whimper.

"Don't you cry, Bambino," she soothed. "We all have our troubles. You must be a brave cat and bear up under yours," and she tiptoed up the red steps and set him at the door where they could find him when they missed him.

He sat there, a crumpled, black, discouraged ball, his eyes following her hungrily.

She ran back to him.

"Bear up under it the best you can, Bambino," she implored; "but if it gets so you can't stand it again, you know where to find a friend."

There was a sound of approaching footsteps in the hall.

She pressed her lips to Bambino's ear, whispered her address to him, and fled.

|

INTERVIEWING MARK TWAIN'S CAT I was working for a certain New York paper. I had made a great hit up there with an interview with Mrs. Reader, the promoter, so great a hit that everybody in the Sunday department arose when I entered the room and offered me chairs, and my wages were raised! "I see," said the Sunday editor, "that Mark Twain's cat has run away. Go down and find out why. Get an interview with Mr. Clemens if you can, and bring it to me." I forthwith meandered down and hung about the beautiful Fifth avenue residence of the noted humorist for the length and breadth of a sunny afternoon. He would see me after luncheon, said the blue-eyed butler first -- he had eyes like a china doll's. Then he would see me at 5 o'clock tea; he seldom got up till 5, the butler informed me, and the cat lay curled up by him through the day. And then at 5 o'clock the butler told me he would see me at dinner time. At dinner time the blue-eyed butler slammed the distinguished door in my common-or-garden face with a curt: "Mr. Clemens doesn't care to see you at all." Well! The cat had got out of the bed of the humorist, and coming down to see what the matter was, had been shut out, too. He brushed against my desolate skirts as I went down the steps, grieving over my lost afternoon and opportunity. I took him up in my arms, and, walking down the street with him, interviewed him. I condoled with him for being obliged to lie curled up all day long on the bed of the alleged humorist -- yes, that is what I dared to call him in my chagrin. I told him I didn't blame him at all for running away, I would have done the same exactly, and added a few more caustic remarks on the same order and in the same vein. The interview with the cat was published. On the following Monday I went cheerily to the office for my weekly suggestions as to work. I was met by a frigid silence, the thickness of ice. They raised their heads and looked me over, but almost immediately lowered them again. Not a soul of them arose, as ordinarily, to offer me a chair. But I was permitted to stand there against the door without being ordered out, and that was something. It was not long before I discovered the why and wherefore. I had offended a great man, the leading humorist of the day. I had dared to have some fun out of him. As a matter of fact, I understood later that he had laughed at the article, but then they didn't know that. A thundering reprimand had come down from the office of the proprietor. The Sunday editor, on account of that interview of mine with Mark Twain's cat, had come within an ace of losing his job. It required some weeks of tactful diplomacy to reinstate myself with the Sunday editor, but after that I took the precaution to carry a little campstool along with me to that office, so as to be sure of a place to sit down should I possess the inclination. - From "A Common or Garden Reporter," by Zoe Anderson Norris in the Bohemian for December. - from the Bellingham (Washington) Herald, December 14, 1906 |

Return

to The New York Times index

Quotations | Newspaper Articles | Special Features | Links

| Search