MARK TWAIN HOME AGAIN

WHAT HE SAYS ABOUT THE NEW BOOK HE HAS WRITTEN.

A WORK SOMETHING LIKE "INNOCENTS ABROAD" - LONGING FOR A RIDE ON THE ELEVATED ROAD - AN AUDIENCE THAT WAITED IN VAIN FOR A STUPENDOUS JOKE.

Mr. Samuel L. Clemens, who is much better known to Americans as Mark Twain, the pilgrim who was moved to tears while leaning upon the tomb of Adam, and the nearest surviving kin of the jumping frog of Calaveras, reached this City in the steamship Gallia yesterday, after an absence of a year and a half in Europe. Mr. Twain was accompanied by his wife, 12 trunks, and 22 freight packages; and the entire party, after a smooth voyage, arrived in good health and spirits, and were met and welcomed down at Quarantine by a number of friends. During his absence he has visited London, Paris, Heidelberg, Munich, Venice, and a number of other cities, spending most of his time on the Continent, and making prolonged stays in Paris, Heidelberg, and Munich. When Mark Twain went away, it was generally believed that his intention was to familiarize himself with German, that he might prepare or two scientific works that are still lacking in that language. He not only did not deny these reports, but rather encouraged them, and his taking passage in a German steamer added greater probability to them. It is now certain, however, that such was not his object. He did have some designs upon the German language, but not with the intention of producing a scientific work. A very celebrated Professor in Munich, who has since died, wrote him a long German letter, inquiring about the point of one of the jokes in "Innocents Abroad," and Mr. Twain desired to learn enough of the language to explain away the difficulty. After more than a year of study he says he can read German well enough, but that, when it comes to talking, English is good enough for him.

"Yes," said he, in response to questions asked by a group of reporters who surrounded him on all sides, except that occupied by the saloon table, so thickly that he could not fill out his Custom house declaration, "I have been writing a new book, and have in nearly finished, all but the last two or three chapters. The first half of it, I guess, is finished, but the last half has not been revised yet; and when I get at it I will do a good deal or rewriting and a great deal of tearing up. I may possibly tear up the first part of it, too, and rewrite that." With all this tearing up in prospect, the book seemed in such danger of being entirely destroyed that one of the reporters suggested the production of a few chapters in advance in the newspapers, as samples; but Mr. Twain said that the manuscript was in the bottom of one of his trunks, where it could not possibly be reached. He added, however, that the book was descriptive of his latest trip and the places he visited, entirely solemn in character, like the "Innocents Abroad" and very much after the general plan of that work; and that it has not yet been named. It is to be published by the same company that brought out his other books, and is to be ready in November. "They want me to stay in New York and revise it," he continued, "but I cannot possibly do that. I am going to start tomorrow morning for Elmira, where we will stay for some time."

On his outgoing voyage, Mr. Twain had for fellow passengers Mr. Bayard Taylor, the American Minister to Germany, and Mr. Murat Halstead who started on five minutes' notice, and without any clothes except those he wore. "I did not see Mr. Taylor after we left the ship," he said, "but corresponded frequently with him. His death was a great surprise to me. Oh, no, I did not lend Mr. Halstead any clothes. He could not get into mine; and, besides, I hadn't any more than I wanted for myself."

The age of the author of "Innocents Abroad," Roughing It," and "The Gilded Age," has not increased apparently, in the last two years. His hair is no whiter than when he last sailed for Europe. He is very much the same man, except that he went away in a silk cap and came back in a cloth hat. He was particularly well pleased with the steamer. "I don't like some of these vessels," said he, "some of them keep a man hungry all the time unless he has a good appetite for boiled rice. I know some steamers where they have the same bill of fare they used to have when the company ran sailing packets: beans on Tuesday and Friday, stewed prunes on Thursday, and boiled rice on Wednesday; all very healthy, but very bad. But we are fed like princes aboard here, and have made a comfortable voyage. We have been in some seas that would have made the old Quaker City turn somersaults, but this ship kept steady through it all. We could leave a mirror lying on the washstand, and it would not fall off. If we stood a goblet loose on the shelf at night, it would be there in the morning." Mr. Twain declined positively, however, to say whether a cocktail, left standing on the shelf at night, would be there all safe in the morning. The ship was hardly steady enough for that.

There was a little ponderous silence that no one interrupted, for the returning writer was evidently revolving something in his mind. "I want a ride on one of the elevated railroads," said he, "I've never been on one of them yet. I used to be afraid of them, but it's no use. Death stares us in the face everywhere, and we may as well take it in its elevated form. I have a friend who wanted to ride on the elevated when the first one was built; but when he looked at it he thought of his wife and children, and concluded to walk home. On the way up town a woman who was washing a third story window fell out, and just grazed my friend's head. She was killed, and he had a very narrow escape. It's no use; there are women washing windows everywhere, and we may as will fall as be fallen upon."

"This new book of mine," said he, breaking suddenly off from the Custom house blanks, "is different from any book I ever wrote. Before, I revised the manuscript as I went a long, and knew pretty well at the end of each week how much of the week's work I should use, and how much I should throw away. But this one has been written pretty much all in a lump, and I hardly know how much of it I will use, or how much will have to be torn up. When I start at it I tear it up pretty fast, but I think the first half will stand pretty much as it is. I am not quite sure that there is enough yet prepared, but I am still at work at it." The group of reporters and five or six listening cabin passengers stood by waiting for something stupendous in the way of a joke to follow all this serious talk. Several times Mr. Twain's lips moved, as if about to speak, but he was silent. The upper end of Staten Island was passed, and the joke was still unborn. Governor's Island came alongside, the Battery drew astern, the Cunard pier was reached, and yet the joker by profession and reputation kept his audience in suspense. The landing was made, but the joke still lay locked up, with the manuscript, in the bottom of the trunk.

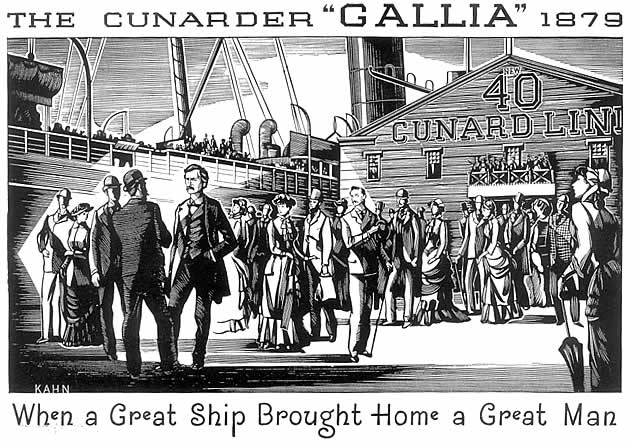

This illustration

was used by the Cunard Line of ships in a 1930 magazine advertisement.

Return to The New York Times

index

Quotations | Newspaper Articles | Special Features | Links

| Search