Home | Quotations | Newspaper Articles | Special Features | Links | Search

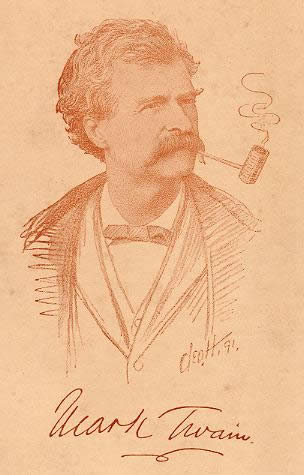

Portrait from The Idler |

THE

IDLER

|

I

HAVE been asked to interview Mark Twain for The Idler. I have refused

to do so, and I think it only fair to the public to state my reason for the

refusal, before beginning the interview. It is simply because I am afraid of

Mark Twain. When we were talking about interviews a short time since, he said

to me in slow and solemn tones that would have impressed a much braver man than

I am:

I

HAVE been asked to interview Mark Twain for The Idler. I have refused

to do so, and I think it only fair to the public to state my reason for the

refusal, before beginning the interview. It is simply because I am afraid of

Mark Twain. When we were talking about interviews a short time since, he said

to me in slow and solemn tones that would have impressed a much braver man than

I am:

"If anyone interviews me again, I will send him a bill for five times what I would charge for an article the length of the interview." Now such a threat means financial ruin to an ordinary man. However modest Mark Twain himself may be, his prices do not share that virtue with him. Baron Rothschild might be able to write a few words on a cheque which would cause that piece of penmanship to be of more value in the commercial world than a bit of Mark Twain's manuscript, but few men have the gift of making their "copy" as costly as the Baron and Mark Twain. I should very likely spend the rest of my natural life in eluding that gentleman and the bailiffs he employed. I have no desire to incur such a liability as would be represented by five times the amount of Twain's inflated prices. I have, therefore, invited several estimable gentlemen to assist me in this hazardous adventure. In union there is strength, and while Mark Twain might run one of us down, he will find his hands full if he attempts to deal with us altogether.

The pictures which illustrate this interview with Mark Twain were taken by a small but industrious Kodak, which

"Held him with its glittering eye,"

on board the French liner, "La Gascogne," at that moment approaching Havre. The anecdotes in the second section of this interview have been written for The Idler by Mr. Joseph Hatton.

WHAT

do I know about Mark Twain ? Not much. Nothing that is not pleasant. I would,

stick to that even if I were under cross-examination. No amount of bullying

should induce me to try and remember anything that is not to his credit, as

a man, an author, and--a champion prevaricator. I don't know when I have liked

him most--when he has been telling the truth, and when he has not. What a pleasant,

tantalising little, kind of stammer it is! Charles Lamb's was a real stutter--it

must have been very delightful; and Travers, of New York, how captivating was

his impediment!

WHAT

do I know about Mark Twain ? Not much. Nothing that is not pleasant. I would,

stick to that even if I were under cross-examination. No amount of bullying

should induce me to try and remember anything that is not to his credit, as

a man, an author, and--a champion prevaricator. I don't know when I have liked

him most--when he has been telling the truth, and when he has not. What a pleasant,

tantalising little, kind of stammer it is! Charles Lamb's was a real stutter--it

must have been very delightful; and Travers, of New York, how captivating was

his impediment!

"Why, Mr. Travers," said a lady, do you stammer more in New York than you did in Baltimore."

"B--b--bigger place," stammered Travers.

A chestnut you say? Well, what of that? There are chestnuts and chestnuts. Some men's chestnuts are better worth having than other men's newest stories. But as I was saying, Mark Twain's is not exactly a stutter; it is a drawl; not perhaps a drawl. Is it simply that he pauses in the right place? Or has he a dialect? It is quite clear he knows the value of his peculiarity of speech whatever it is. Did you hear him lecture in London? The point that broke the general titter into a hearty laugh was when he talked about that very cold mountain out in Fiji or somewhere; it is so cold up there that people can't speak the truth--I know, because I have been there."

When Mark Twain paid his earliest visit to London, he did me the honour once or twice to sit under my mahogany. The first time he came to my house it was to meet some thirty pleasant people at supper. It was his first entertainment in town. He was very desirous of observing the customs of the country. He came in a dress coat. That was all right. He was very glad he had put on his dress coat. He took the late Mrs. Howard Paul, a very clever, charming woman, down to supper. He consulted her touching certain social customs. She was in her way quite a humorist, and in those days a bright and lively woman. Knowing that on no account did I ever permit speech-making at my table ; knowing, indeed, that even in artistic society this kind of thing is never resorted to, she explained to Mark Twain that quite the contrary was the case; that if he desired really to show that he was up to all the little tricks of the great world of London, he would, as the greatest stranger, if not the most important guest, rise and propose the host's health; that everybody would expect it from him, and so on. Presently, to the astonishment of everybody, Mark Twain arose, tall and gaunt, and began to drawl out in his odd if fascinating manner a series of complimentary comments upon the host, at the same time apologising for not being quite prepared with a speech, for the reason that the lady on his right had been instructing him all the night with personal stories of everybody at the table. The table squirmed a little at this. It had "no call" to squirm. It was above reproach. Genius, beauty, wealth, and even the nobility (he was a real lord if he was but a little one) were well represented; but you might have thought from his manner that Mark Twain had heard some very strange stories of his fellow-guests. It was a happy, clever, odd little speech; and both he and Mrs. Paul were forgiven--he for making it, she for misleading him as to the manners and customs of the world of Upper Bohemia.

If you are a humorist you can make mistakes that are condoned as witticisms; you can even be stupid, and someone will find fun in your very stupidity. People have always half a grin on their faces ready for the professed humorist before he begins to speak. I am not a humorist. One night at Kensington Gore, when the late Mr. Bateman, the Lyceum manager, lived there, Irving told to Mark Twain and half a dozen others a very good story about a sheep. It was a very racy story, racy of the soil, I said, the soil being Scotland. Irving told it well, dramatising some of the incidents as he went along. He was encouraged to do so by the deep interest Twain took in it. I suggested to Twain that he should make a note of it; it seemed to me that it was one of those nationally characteristic anecdotes that was worth remembering, because it was characteristic, and national. Twain said, "Yes, he thought it a good idea to make a note or two of English humour--of national anecdotes in particular." He took out a small book, and quite won my heart by the modest, quiet way in which he made his memoranda about this story; I even gave him one or two points about it, fresh points. We were sitting in a corner of the room by this time, chatting in a friendly way, and Mark Twain seemed more than necessarily grateful for my suggestions. I had reason afterwards to wonder whether he thought was chaffing him, or whether he was chaffing me. I did not know any more than Irving did that the story about the sheep was really one of Mark Twain's own stories.

I was innocent enough about it anyway, and Irving had never heard, I'll be bound, of the Hotten volume in which the narrative of the sheep and the good Samaritan had been set forth in Twain's best manner. It is quite possible that to this day Mark Twain is under the impression that I was engaged in a pleasant piece of fooling at Bateman's that night, and believed himself to be just as pleasantly checkmating me. Of course, he saw through the whole business. He pretended to fall into my little trap, which was not a trap at all. Perhaps he thought I was a humorist.

Do you know that he smokes three hundred cigars a year--or a month, I forget which--and that he once tried to break off the habit against which King James uttered his great but ineffective blast, and that after a fair test of life with and without tobacco he came to the conclusion that a weedless life would be too utter a failure even for an accidental humorist. He was no doubt right. I wonder if he consulted his conscience about it? Do you remember, how his conscience once visited him? It was his conscience, was it not? A little wizened, pinched thing that hopped about his study and talked to him. I don't' remember a more weird bit of satire than his account of that strange visit. Such an egotistical, deformed little chap! And with such wise, strange, cutting words! I think I liked our friend the better for his story of that graphically narrated meeting with his conscience, Mark Twain told an interviewer the other day that he disliked humorous books; that he was only himself a humorist by accident. But what has he not told interviewers?

MR.

HATTON appears to be in doubt whether Mark Twain smokes three hundred cigars

a year-or a month. There is a slight difference both to tobacconist and consumer.

I have been told that his annual, allowance is three thousand cigars. But it

must not be thought that his devotion to tobacco stops at this trivial quantity.

The cigars merely represent his dessert in the way of smoking. The solid repast

of nicotine is taken by means of a corn-cob pipe. The bowl of this pipe is made

from the hollowed-out cob of an ear of Indian corn. It is a very light pipe,

and it colours brown as you use it, and ultimately black, so they call it in

America "The Missouri Meerschaum." I was much impressed by the ingenuity

with which Mark Twain fills his corn-cob pipe. The humorist is an inspired Idler.

He is a lazy man, and likes to do things with the least trouble to himself.

He smokes a granulated tobacco which he keeps in a long check bag made of silk

and rubber. When he has finished smoking, he knocks the residue from the bowl

of the pipe, takes out the stem, places it in his vest pocket, like a pencil

or a stylographic pen, and throws the bowl into the bag containing the granulated

tobacco. When he wishes to smoke again (this is usually five minutes later)

he fishes out the bowl, which is now filled with tobacco, inserts the stern,

and strikes a light. Noticing that his pipe was very-aged and black, and knowing

that he was about to enter a country where corn-cob pipes are not, I asked him

if he had brought a supply of pipes with him.

MR.

HATTON appears to be in doubt whether Mark Twain smokes three hundred cigars

a year-or a month. There is a slight difference both to tobacconist and consumer.

I have been told that his annual, allowance is three thousand cigars. But it

must not be thought that his devotion to tobacco stops at this trivial quantity.

The cigars merely represent his dessert in the way of smoking. The solid repast

of nicotine is taken by means of a corn-cob pipe. The bowl of this pipe is made

from the hollowed-out cob of an ear of Indian corn. It is a very light pipe,

and it colours brown as you use it, and ultimately black, so they call it in

America "The Missouri Meerschaum." I was much impressed by the ingenuity

with which Mark Twain fills his corn-cob pipe. The humorist is an inspired Idler.

He is a lazy man, and likes to do things with the least trouble to himself.

He smokes a granulated tobacco which he keeps in a long check bag made of silk

and rubber. When he has finished smoking, he knocks the residue from the bowl

of the pipe, takes out the stem, places it in his vest pocket, like a pencil

or a stylographic pen, and throws the bowl into the bag containing the granulated

tobacco. When he wishes to smoke again (this is usually five minutes later)

he fishes out the bowl, which is now filled with tobacco, inserts the stern,

and strikes a light. Noticing that his pipe was very-aged and black, and knowing

that he was about to enter a country where corn-cob pipes are not, I asked him

if he had brought a supply of pipes with him.

"Oh, no," he answered, "I never smoke a new corn-cob pipe. A new pipe irritates the throat. No corn-cob pipe is fit for anything until it has been used at least a fortnight."

"How do you manage then?" I asked. "Do you follow the example of the man with the tight boots;--wear them a couple of weeks before they can be put on?"

"No," said Mark Twain, "I always hire a cheap man--a man who doesn't amount to much, anyhow--who would be as well--or better--dead, and let him break in the pipe for me. I get him to smoke the pipe for a couple of weeks, then put in a new stem, and continue operations as long as the pipe holds together."

Mark Twain brought into France with him a huge package of boxes of cigars and tobacco which he took, personal charge of when he placed it on the deck while he lit a fresh cigar he put his foot on this package so as to be sure of its safety. He didn't appear to care what became of the rest of his luggage as long as the tobacco was safe.

"Going to smuggle that in?" I asked.

"No, sir. I'm the only man on board this steamer who has any tobacco. I will say to the Customs officer, 'Tax me what you like, but don't meddle with the tobacco.' They don't know what tobacco is in France."

Another devotee of the corn-cob pipe is Mr. Rudyard Kipling, who is even more of a connoisseur in pipes than is Mark Twain, which reminds me that Mr. Kipling interviewed Mr. Clemens, and, although the interview has been published before, I take the liberty of incorporating part of it in this symposium.

He

re-curled himself into the chair and talked of other things.

He

re-curled himself into the chair and talked of other things.

"I spend nine months of the year at Hartford. I have long ago satisfied myself that there is no hope of doing much work during those nine months. People come in and call. They call at all hours, about everything in the world.

One day I thought I would keep a list of interruptions. It began this way. A man came but would see no one but Mr. Clemens. He was an agent for photogravure reproductions of Salon pictures. I very seldom use Salon pictures in my books. After that man another man, who refused to see anyone but Mr. Clemens, came to make me write to Washington about something. I saw him. I saw a third man. Then a fourth. By this time it was noon. I had grown tired of keeping the list. I wished to rest. But the fifth man was the only one of the crowd with a card of his own. Ben Koontz, Hannibal, Missouri. I was raised in Hannibal. Ben was an old schoolmate of mine. Consequently I threw the house wide open and rushed with both hands out at a big, fat, heavy man, who was not the Ben I had ever known--nor anything of him. 'But is it you, Ben?' I said. 'You've altered in the last thousand years.' The fat man said, 'Well, I'm not Koontz, exactly, but I met him down in Missouri, an' he told me to be sure and call on you, an' he gave me his card and'--(here he acted the little scene for my benefit)--, if you'll wait a minute till I can get out the circulars--I'm not Koontz, exactly, but I'm travelling with the fullest line of rods you ever saw.' "

And what happened?" I asked breathlessly.

I shut the door. He was not Ben Koontz, exactly, not my old schoolfellow, but I had shaken him by both hands in love, and I had been boarded by a lightning-rod man in my own house. As I was saying, I do very little work in Hartford. I come here for three months every year, and I work four or five hours a day in a study down the garden of that little house on the hill. Of course I do not object to two or three interruptions. When a man is in the full swing of his works these little things do not affect him. Eight or ten or twenty interruptions retard composition."

I was burning to ask him all manner of impertinent questions, as to which of his works he himself preferred, and so forth, but standing in awe of his eyes I dared not. He spoke on and I listened.

It was a question of mental equipment that was on the carpet and I am still wondering whether he meant what he said.

"Personally I never care for fiction or story books. What I like to read about are facts and statistics of any kind. If they are only facts about the raising of radishes they interest me. Just now, for instance, before you came in"--he pointed to an Encyclopaedia on the shelves--"I was reading an article about mathematics--perfectly pure mathematics. My own knowledge of mathematics stops at twelve times twelve, but I enjoyed that article immensely. I didn't understand a word of it, but facts--or what a man believes to be facts--are always delightful. That mathematical fellow believed in his facts. So do I. Get your facts first, and"--the voice died away to an almost inaudible drone-- "then you can distort 'em as much as you please."

Bearing this precious advice in my bosom I left, the great man assuring me with gentle kindness that I had not interrupted him in the least. Once outside the door I yearned to go back and ask some questions--it was easy enough to think of them now--but his time was his own, though his books belonged to me.

I should have ample time to look back to that meeting across the graves of the days. But it was sad to think of the things he had not spoken about. In San Francisco the men of the Call told me many legends of Mark's apprenticeship in their paper five and twenty years ago--how he was a reporter, delightfully incapable of reporting according to the needs of the day. He preferred, so they said, to coil himself into a heap and meditate till the last minute. Then he would produce copy bearing no sort of relationship to his legitimate work-copy that made the editor swear horribly and the readers of the Call ask for more. I should like to have heard Mark's version of that and some stories of his joyous and renegated past. He has been journeyman printer (in those days he wandered from the banks of the Missouri even to Philadelphia), pilot cub, and full-blown pilot, soldier of the South (that was for three weeks only), private secretary to a Lieutenant-Governor of Nevada (that displeased him), miner, editor, special correspondent in the Sandwich Islands, and the Lord only knows what else.

I

ASKED Mark Twain if he remembered Kipling's visit to him at Elmira He said he

did. He was apparently much impressed by the young Anglo-Indian, and thought

the young man would be heard from, although, at the time, he was entirely unknown.

Twain kept Kipling's card, and when the latter became famous he looked up the

card, and found that the writer who had caused such a sensation in the literary

world of London was the man who had visited him. This gave Mark Twain the opportunity

of remarking, "I told you so," which he generously refrained from

saying. He thinks that young writers might profitably study the works of Kipling

if they wish to see how a story can be tersely, vigorously, humorously, and

dramatically told.

I

ASKED Mark Twain if he remembered Kipling's visit to him at Elmira He said he

did. He was apparently much impressed by the young Anglo-Indian, and thought

the young man would be heard from, although, at the time, he was entirely unknown.

Twain kept Kipling's card, and when the latter became famous he looked up the

card, and found that the writer who had caused such a sensation in the literary

world of London was the man who had visited him. This gave Mark Twain the opportunity

of remarking, "I told you so," which he generously refrained from

saying. He thinks that young writers might profitably study the works of Kipling

if they wish to see how a story can be tersely, vigorously, humorously, and

dramatically told.

Mark Twain has not a very high opinion of interviewers in general. He said, "I have, in my time, succeeded in writing some very poor stuff, which I have put in pigeonholes until I realised how bad it was, and then destroyed it. But I think the poorest article I ever wrote and destroyed was better worth reading than any interview with me that ever was published. I would like," he added, "just once to interview myself in order to show the possibilities of the interview." He partly promised to do this, and let me have the result, so that it might be published in The Idler, but up to the hour of going to press the "copy" has not been received. I tried to show him the vast opportunities that lie before the man who interviews himself. I told him that if he did it truthfully and faithfully there was every chance of his being arrested the moment he set foot in any civilised country. A man knows his own weak points, and can, therefore, cross-examine himself with an effectiveness that a stranger could not hope to emulate. If he has committed any crimes he can lay them bare, and although he can escape the inquisitiveness of an outside interviewer, he cannot escape from himself.

We were leaning over the rail of the steamer as I pictured to him the advantages of self-interviewing, and I fancied that his bronzed cheek became paler as he fully realised the possibilities. I do not wish to accuse the humorist of anything indictable, but merely want to point out that up to date he has not attempted that interview with himself.

I give now an extract from an interview which Mark Twain did not like. He says that the man who interviewed him did so for the purpose of publishing the interview in England, but sold it instead to a New York paper. "They come," says Mark Twain, "to me on the social tack, and visit my house with a letter of introduction. I try to treat them well, and then the next thing I know the conversation appears in some paper."

I

HOLD that T. B. Aldrich is the wittiest man I ever met. I don't believe his

match ever existed on this earth.

I

HOLD that T. B. Aldrich is the wittiest man I ever met. I don't believe his

match ever existed on this earth.

It is not guesswork,

this estimate of mine as regards the limits of my humour and my power of appreciating

humour generally, because with my book-shelf full of books before me I should

certainly read all the biography and history first, then all the diaries and

personal memoirs, and then the dictionaries and the cyclopaedias. Then, if still

alive, I should read what humorist books might be there. That is an absolutely

perfect test and proof that I have no great taste for humour. I have friends

to whom you cannot mention a humorous book they have not read. I was asked several

years ago to write such a paper as that you suggest on humour, and the comparative

merits of different national humour, and I began it, but I got tired of it very

soon. I have written humorous books by pure accident in the beginning, and but

for that accident I should not have written anything.

At the same time

that leaning towards the humorous, for I do not deny that I have a certain tendency

towards humour, would have manifested itself in the pulpit or on the platform,

but it would have been only the embroidery, it would not have been the staple

of the work. My theory is that you tumble by accident into anything. The public

then puts a trademark on to your work, and after that you can't introduce anything

into commerce without the trademark. I never have wanted to write literature;

it is not my calling. Bret Harte, for instance, by one of those accidents of

which I speak, published the 'Heathen Chinee,' which he had written for his

own amusement. He threw it aside, but being one day suddenly called upon for

copy he sent that very piece in. It put a trademark on him, at once, and he

had to avoid all approaches to that standard for many a long day in order that

he might get rid of that mark. If he had added three or four things of a similar

nature within twelve months, he would never have got away from the consequences

during his lifetime. But he made a purposely determined stand; he abolished

the trademark and conquered."

Whether Mark Twain liked the above interview or not, it is certainly true in one respect--that he thinks Mr. T. B. Aldrich the most humorous man in America. Mr. Clemens looks upon himself as, in reality, a serious man, and a glance at the excellent portrait published as a frontispiece to this magazine will show that his looks carry out the idea. He said that he and Aldrich were staying together at an hotel in Rome. Aldrich came in and said to him, "Clemens, you think you're famous! You have conceit enough for anything. Now, you don't know what real popularity is. I have just been asking that man on the Piazza di Spagna for my books. He hasn't one,--not one. They're all sold. He simply can't supply the demand. It's the same all over Europe. I've never seen one of my books anywhere. They're gone. Now, look at your books. Why, that unfortunate man on the Piazza has 1,600 of them. He's ruined, Clemens. He'll never sell 'em. The people are reading mine. That's genuine popularity."

IN

this number of The Idler, Mark Twain begins his new story, "The

American Claimant." Although the novelist does not say so, it is evident

that the story was suggested to him by his own family history. This fact comes

out incidentally in Mark, Twain's article, entitled "Mental Telegraphy,"

which appeared in Harper's Magazine for December, 1890. In relating the

extraordinary experience's he has had in mental telegraphy, Mark Twain says:--

IN

this number of The Idler, Mark Twain begins his new story, "The

American Claimant." Although the novelist does not say so, it is evident

that the story was suggested to him by his own family history. This fact comes

out incidentally in Mark, Twain's article, entitled "Mental Telegraphy,"

which appeared in Harper's Magazine for December, 1890. In relating the

extraordinary experience's he has had in mental telegraphy, Mark Twain says:--

My mother is descended from the younger of two English brothers, named Lambton,

who settled in America a few generations ago. The tradition goes that the elder

of the two eventually fell heir to a certain estate in England (now an earldom),

and died right away. This has always been the way with our family, they always

die when they could make anything by not doing it. The two Lambtons left plenty

of Lambtons behind them; and when, at last, about fifty years ago, the English

baronetcy was exalted to an earldom, the great tribe of American Lambtons began

to bestir themselves--that is, those descended from the elder branch. Ever since

that day, one or another of these has been fretting his life uselessly away

with schemes to get at his 'rights.' The present 'rightful earl'--I mean the

American one--used to write me occasionally, and try to interest me in his projected

raids upon the title and estates by offering me a share in the latter portion

of the spoil; but I have always managed to resist his temptations.

Well, one day last summer, I was lying under a tree, thinking about nothing in particular, when an absurd idea flashed into my head, and I said to a member of the household, 'Suppose I should live to be ninety-two, and dumb and blind and toothless, and just as I was gasping out what was left of me, on my death- bed--'

'Wait, I will finish the sentence,' said the member of the household.

'Go on,' said I.

'Somebody should

rush in with a document, and say, 'All the other heirs are dead, and you are

the Earl of Durham!'

That is truly what I was going to say. Yet until that moment the subject had

not entered m mind or been referred to in my hearing for months before. A few

years ago this thing would have astonished me, but the like could not much surprise

me now, though it happened every week; for I think I know now that mind can

communicate accurately with mind without the aid of the slow and clumsy vehicle

of speech."

This conglomerate interview will now be concluded by a poem from the pen of Oliver Wendell Holmes, which, as far as I know, has never before been published in England.

|

AH!

Clemens when I saw thee last,

We both of us were younger, How fondly mumbling o'er the past Is memory's toothless hunger. So 50 years have fled, they say, Since first you took to drinkin, I mean in Nature's milky way Of course no ill I'm thinking. But while on life's uneven road Your track you've been pursuing, What fountains from your wit have flowed- What drinks you have been brewing! I know whence all your magic came, Your secret I've discovered, The source that fed your inward flame- The dreams that round you hovered: |

Home |

Quotations | Newspaper Articles

| Special Features |

Links | Search