Home | Quotations

| Newspaper Articles

| Special Features |

Links | Search

SPECIAL FEATURE

Mark Twain's Writings on Fasting and Health

plus

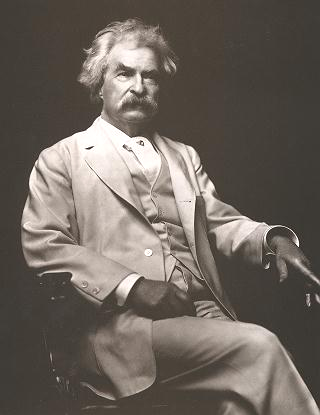

The Story Behind the A. F. Bradley Photos

A. F. Bradley photos provided by Dave Thomson.

|

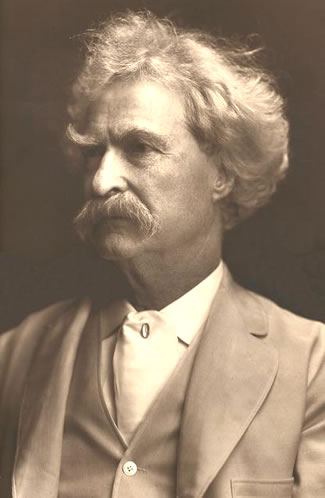

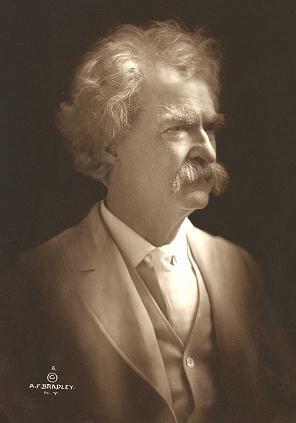

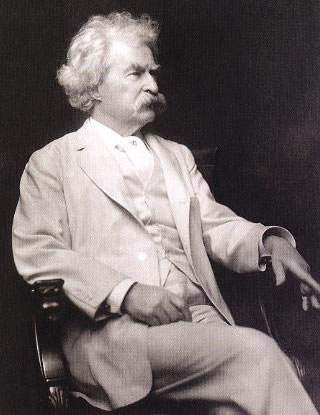

In May 1919 writer George Wharton James published an article in Physical Culture magazine discussing Mark Twain's news report of the 1866 Hornet disaster first published in the Sacramento Daily Union. The article also appeared in the December 1866 issue of Harper's Magazine under the title "Forty-three Days in an Open Boat." In 1899, Twain again wrote of the incident in "My Debut as a Literary Person." James'

article illustrates how the Hornet incident impacted Twain's

later sketch titled "At the Appetite

Cure."

The Physical Culture article was unique in that it published

for the first time some photos of Twain taken by renown photographer

A. F. Bradley. James revealed how he was instrumental in convincing

Twain to pose for these photos as a fund raising effort to benefit survivors

of the San Francisco earthquake disaster. (It

was a cause to which Twain had already lent his support). The Bradley

photos survive today as some of the most popular of Twain ever taken

and continue to be favorite choices for a number book jackets and posters.

The following is the complete text of James' article including photos

that accompanied it. |

He began life as Samuel L. Clemens and ended it as Mark Twain. He was America's foremost humorist, philosopher and man of letters. |

Physical Culture

May 1919

MARK TWAIN - An Appreciation of His Pioneer

Writings on Fasting and Health (Part I)

by George Wharton James

ILLUSTRATED BY HITHERTO UNPUBLISHED COPYRIGHT PHOTOGRAPHS BY A. F. BRADLEY, NEW YORK

|

And now it becomes my pleasure to tell how the accompanying photographs of Mark Twain--never before seen by the public--were obtained. In the early days of Mark Twain's life, as is well known, he lived in San Francisco. Among his intimates there were Bret Harte, Joaquin Miller, Noah Brooks, Charles Warren Stoddard, Prentice Mulford, and a few others of a rare coterie who made California Literature famous throughout the world. The Queen of this little circle was Ina Donna Coolbrith, a poet of no mean order. Then the disastrous earthquake and following fire, of 1906, struck San Francisco, Miss Coolbrith was one of the many sufferers, who was made destitute and homeless. Instantly her friends came to the rescue. Among other methods followed for raising the money was that of writing to authors to contribute an autographed copy of one of their books or a photograph, which could then be sold. Mark Twain was one of the earliest to respond, and sent three fine autographed photographs, which I speedily sold for ten dollars each. |

| Soon afterwards, being in New York, in the Fifth Avenue Studio of Wm. A. F. Bradley, one of the most successful studio photographers in the world, it occurred to me that if I could get Mark Twain to pose, and Mr. Bradley would make me some photographs at a wholesale price, and Mark would then autograph them, I could sell quite a number, to the happy increase of our "Ina Coolbrith Home Fund." Mr. Bradley agreed and said he would help make the posing as easy as possible by building a revolving platform, to save the usual troubles and annoyances of constantly moving the sitter to produce the proper effects of light and shade. |  |

|

The main difficulty in the way was to get Mark Twain to pose. Accordingly I wrote to his secretary, Miss Lyon, and received a very courteous note saying that he was overwhelmingly busy upon some work he had pledged himself to accomplish in a given time, and had given positive orders that no one, under any circumstances, was to be given an interview or disturb his privacy. This seemed to be final, but the more I thought about it the more desperate the case appeared. I should be in New York for a short time only, and I could not hope to succeed by a letter. I must see him personally. Accordingly I took the bull by the horns, and one morning appeared at his Fifth Avenue residence, Miss Lyon met me with a reproving as well as reproachful look upon her face: "I dare not even tell Mr. Clemens you are here. It is contrary to his express and positive orders." "Never mind," said I, "I'll tell him myself. Where is he?" |

I felt pretty well assured that he was upstairs, in bed, writing as was his wont. For he had the habit of several literary men I know, who always preferred to do their creative work with as few clothes on as possible. I forget whether Miss Lyons or I first called up the stairs to let him know I was there, but I do know that in a few moments a stream of talk that would not look well in a Sunday School book came down stairs. At first he refused point blank to come down, but I threatened to come up and "beard the lion in his den." The dire vengeance he vowed he would wreak upon me if 1 did this held me back, but I vowed I would camp at the foot of the stairs until he came down. I said in effect, "You profess the greatest friendship for Miss Coolbrith and say you would do anything on earth for her. Now let us see how much this means." Seeing that I was persistent, he finally consented to dress and come down stairs. When he did so, though he was undeniably ruffled, he was the courteous gentleman, and expressed himself as desirous of doing anything he could, in reason, to aid in what we were attempting to accomplish. But, when I suggested that he go to Mr. Bradley's studio and pose, it seemed too much. "I'll never do it." he exclaimed. "I've vowed I'd never be photographed again. You know those photographs I sent to you? Shall I tell you how they got those. Rogers came to me one day and said a man wanted to make some snapshots of me at a picnic. I told him to go ahead, for, of course, I didn't care what he did when I was unconscious of it. But then he came and seduced me into a temporary gallery he'd rigged up and photographed the immortal soul out of me and I swore I'd never go into a photographer's gallery again."

"But," said I, "if he took your immortal soul, you're safe for the future, and your soul doesn't count, anyway."

|

Then I pleaded my cause afresh, and to my great joy, though I cannot tell myself it was my persuasive powers that won the victory -- it was merely to get rid of me -- he consented to go. Yet the promise was no subterfuge. I had to leave New York for the West, so could not go in person with a carriage or taxi for him, but in due time, when Mr. Bradley was ready, he appeared, sat on the chair on the revolving stand, and the pictures herewith were made. Mr. Bradley recalls well his white flannel suit, his peculiar drawl, his pleasant conversation, and the real patience with which he sat until some seventeen negatives in all were made. Of the negatives thus obtained he wrote me that he regarded four as the finest photographs of himself that had ever been taken of him in his life. |

It

was not long thereafter before the world honored him at the great banquet

given in New York on his birthday and then, in time, the news was flashed

over the world's wires that he had "gone home," and one of the greatest

characters the United States had ever produced was laid to rest.